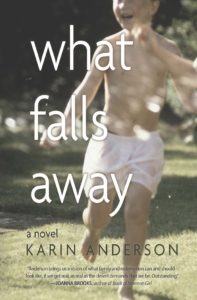

Karin Anderson on her new novel, What Falls Away (Torrey House Press).

Karin Anderson on her new novel, What Falls Away (Torrey House Press).

What Falls Away is a novel set in a town called Big Horn, Utah. Yes, it closely resembles my hometown in northern Utah Valley. It’s the closest portrayal of the estranged familiar as I can bear to write. The work is, however, fictional. I wish to keep calling attention to that, especially for readers who may recognize fragments of “real” time, place, and character.

The narrative does lean hard into elements of my midcentury rural Utah beginnings. Although I write as a nonbeliever and adult outsider, my first life in a gorgeous desert valley troubled by hard doctrines and paranoid social politics informs my subsequent worldviews. As protagonist Cassandra Soelberg explains to a traveler seeking his own perplexing roots: “You can’t ‘used to come’ from someplace. You always come from that place, like it or not.”

I hate-love the unanswerable questions that spin from my uneasy sense of place and kinship, and so I write about them. For me, What Falls Away plays propositions with deeply personal implications: What if I was the girl sent away from community and home to deliver an “illegitimate” child? What if I were a mother of an unreachable and unknown person? How deeply are we genetically informed, and why do any of those genetic elements matter? Why would we imagine that a lost genetic child matters any more than any other?

How do we contend with frightening likenesses and recognitions?

What might it mean to be made from potent biological and cultural ingredients but bear no knowledge of them? How do we name relationships between genetic parents and adoptive parents, “first” families and acquired families? How do we negotiate the mysteries of the ancestral body?

What does it mean – and not mean – to say, “this is my child”? How can any child “belong” to us? What drives parents to disown or disavow their own? What makes those bonds good and what makes them terrible?

When / how do we release our children from our tenacious hold? How do we depart? How do we return? How do lovers / abusers / friends / mentors / fellow travelers change us, become “family” – become us – welcome or not?

Probably the most urgent question that evolved in the process of composition: On this planet, teetering on the precipice of environmental destruction, how do we honor kinship as a field of radical possibilities rather than rote mandates of emulation?

If I knew the answers to any of these questions, I’d write a lot more nonfiction. But I don’t. My favorite question in the whole canon of English-language poetry comes from Theodore Roethke’s poem “The Waking,” which also furnishes the title of What Falls Away: “Of those so close beside me, which are you?” I remember reading that line in an undergraduate lit course. It osmosis-ed into me, gave me new eyes, another heart. Changed the nature of color and light. The line yet anchors my fascination with character – the impenetrability of mundane human surfaces, the interplays of memory, grief, fear, love, power, and impotence beneath.

What Falls Away runs on two timelines: 1970s Utah in past tense, 2019 Utah in present. The novel begins with Cassandra Soelberg’s reluctant return to Big Horn after four decades of estrangement. After exile at sixteen to secretly deliver (and surrender) an infant, disaffection broke her bond with home and family. She made attempts to reconcile during her time in college but departed under her father’s wrath once and for all before she graduated with an art degree.

Now Cassandra’s unknowable mother, a widow, is failing to dementia. Cassandra returns to care for Dorothy at the behest of her oldest brother, James. Cassandra re-enters a house that quarters the uncanny, set in a landscape of primal memory.

The premise helped me contend with some of the practical “problems” of writing about distinctive strains of Mormon experience. For one thing, it filters the “cast of thousands” so characteristic of family and religious community. Cassandra’s initial isolation in the home where she grew up, attending to an increasingly vacant parent, allowed me to re-introduce figures (and configurations) from her childhood one at a time. Returned as a professional artist, an educated and self-realized adult, Cassandra has time (whether she wants it or not) to gaze upon and re-orient scenes of bewildering youthful sorrow.

Situating Cassandra in her cramped childhood home allowed me to literalize the compartmented and sometimes dissociated structures of her post-traumatic psyche. She passes the closed door of her childhood bedroom throughout the narrative but cannot make herself open and enter. Her father’s tool shed stands, locked and untouched since his death, as a monument to his debilitating severity. Every segment of the home and property agitates and re-projects.

Even so, Cassandra’s encounters with old and new figures of “home” accumulate toward a tenuous commitment to re-engage. She grasps lifelines in encounters with genuine friends within and beyond the community. She suspends her visceral terror of maternal hope to allow a compelling (and alarmingly familiar) traveler to engage in rich conversation. She incrementally drops her self-protective aversion to children as she perceives threads of family charm and future. Her respect for her brother Brian allows her to marvel at a man who has salvaged the best of their heritage to create a nearly mythic life for his family, reviving a sense of something Edenic, of beautiful origin and partial (if troubled) recovery.

I’ve spent a lifetime of creative energy fussing over questions of “home,” and none of them ever reach resolution. Whatever settings we manage to claim as home – gladly or not – seem to be, bottom line, the places that won’t be exorcised.

I don’t believe the past is as fixed as our myths and memories insist they are. Fiction allows me to explore alternatives and hypotheticals, loosen the knots of certainty. If we hope to unfasten the future from horrific ideological and scientific “inevitabilities,” I think we need to try to dismantle prophecy too. Cassandra returns with a fixed sense of “home,” certain she will complete an ascetic duty and depart again – a prophecy founded on a suffocating sense of history. At the finish, she stands among kindred – ancestors and descendants, outcasts, stalwarts, friends and enemies, anti-familiars and familiars – and, for the sake of generational supplicants, she drops to the sacred ground to recompose the elements.

I guess in that sense I’ve written myself a role model, even though Cassandra is no savior, no hero. She’s simply an aging woman renegotiating her commitment to relationship, human absurdity, slender hope, agency and creative possibility. Hard love.

Roethke: “What falls away is always. And is near.” For Cassandra, the pain and sweetness of the past, the love and rage and humiliation of a thwarted childhood, the longing for connection and the terror of reunion, will always fall away and always be near. And the children of her past and future will beckon her.

Segments of “The Waking” by Theodore Roethke were used in the novel by permission of Doubleday: Collected Poems by Theodore Roethke, copyright 1966 and renewed 1994 by Beatrice Lushington. Sincere gratitude.

A gardener, writer, mother, wanderer, and heretic, Karin Anderson is the author of the novels Breach and Before Us Like a Land of Dreams. Her work has appeared in Dialogue, Quarter After Eight, Western Humanities Review, Sunstone, Saranac Review, American Literary Review, and Fiddleback. A former professor of English at Utah Valley University, she has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize and holds degrees from Utah State University, Brigham Young University, and the University of Utah. She hails from the Great Basin.

A gardener, writer, mother, wanderer, and heretic, Karin Anderson is the author of the novels Breach and Before Us Like a Land of Dreams. Her work has appeared in Dialogue, Quarter After Eight, Western Humanities Review, Sunstone, Saranac Review, American Literary Review, and Fiddleback. A former professor of English at Utah Valley University, she has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize and holds degrees from Utah State University, Brigham Young University, and the University of Utah. She hails from the Great Basin.

Reviews

Julie J. Nichols, AML. “Read this book. It’ll change how you feel about family. And if you have thought, as I have, that the biases, judgments, and practices of extreme Mormon culture have nothing to do with you, What Falls Away will change how you experience salvation, too.”

Kirkus Reviews. “Anderson crafts a gorgeously descriptive narrative of aging, religious harm, and childhood trauma, complete with colorful characters who mostly eschew Mormon stereotypes. Through present-day Cassandra, the author offers up a refreshing depiction of older women and doesn’t shy away from visible descriptions of age, from graying hair to sagging breasts. The story is also peppered with queer themes and characters . . . A powerful novel that will resonate with anyone who has returned to a place they no longer recognize as home.”