David G. Pace’s new collection of short fiction, American Trinity & Other Stories from the Mormon Corridor, was published this week by BCC Press. To celebrate, we are publishing Christopher T. Lewis’ foreword to the collection, which places Pace’s stories in the context of existing Mormon literature, in particular the tradition of stories about the Three Nephites.

David G. Pace’s new collection of short fiction, American Trinity & Other Stories from the Mormon Corridor, was published this week by BCC Press. To celebrate, we are publishing Christopher T. Lewis’ foreword to the collection, which places Pace’s stories in the context of existing Mormon literature, in particular the tradition of stories about the Three Nephites.

Foreword, by Christopher T. Lewis

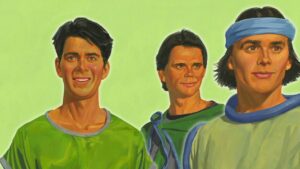

I love Three Nephites stories because, as befits the wandering trinity’s reputation, they catch people off guard. Too often reduced to faith-promoting rumors or punchlines, the weight of their mythos can easily drag their exploits down into theatrics of parody or pageantry. Perhaps it is precisely because they are so easily reduced to a deus ex machina—coming to the rescue of the faithful with car trouble and giving warnings about food storage¹—that midrashic or literary attempts to imbue them with “the full range of psychological and social complexity” have such promise.² After all, one does not expect to be confronted with much humanity in figures who, as immortal plot devices, encompass both God and the machine.

“American Trinity,” the Three Nephites anchor story in this new collection by David G. Pace, resists the theatrics in favor of subtler theater in its approach to the foundational Mormon scripture, a juxtaposition that returns in the concluding entry of the book, “Caliban Revels Now Ended.” From the disillusioned Nephite Zed, frequenting the theater district of Old New York, to a former missionary returning to his mission decades later to review a production of The Tempest (speaking of a deus ex machina), this book renders not just its Nephites but all its characters with a compassion that rises above the excesses of either The Book of Mormon musical or the Hill Cumorah Pageant. It is theater that, in the words of the protagonist of “Caliban,” “transcend[s] both orthodoxy and disbelief.”

Despite their cultural reputation, the Three Nephites are in fact an inspired point of departure for those in search of a nuanced look at the Restoration. Their role in Mormon mythology is less tied to orthodoxy than it first appears. True, on one level they function as the physical proof of The Book of Mormon’s historicity that so many yearn for (see Rell in “Dreamcatcher”). As both participants in and witnesses of the text, they hold the potential to come forth at any time to manifest themselves as a powerful mark of its legitimacy. They tether an ancient account to the present because they exist beyond its pages. The idea that the reader could one day encounter one of them makes the story more current, more alive—more “for our day.”

Even when the Three Nephites show up as angels dressed in white, the very fact that they represent a breach in the fabric of the world adds to its complexity. Neither mortal nor immortal, they are both liberated and confined by the in- between spaces they inhabit. They are time travelers who do not fully belong to the past or the present, caught between the mundane and the miraculous, history and folklore. They have existed for so long that they can no longer distinguish between the text of The Book and their own memories: “I remember little more about the Lord’s sojourn with us than what anyone else can currently read, and I was there! That’s what you call the power of a text,” remarks Zed.

Zed himself draws attention to what most would consider the standard faith-promoting narrative of Three Nephites folklore, which he refers to as “guerrilla ministering.” He tags along with one of his brethren, Kumen, on a mission of comfort and aid to a lonely polygamous wife in the Ute Territory. When Kumen asks for food, she feeds him with the last of her cornmeal, which she had intended for her children. Kumen makes sure to hit all the right beats, replenishing her supply and disappearing before she has a chance to thank him. This is just the sort of event whose miraculous quality tends to escalate in the right hands. Zed, one of the scribes who shaped The Book of Mormon—and admittedly exaggerated that aspect of it—might have been tempted to add another layer to the miracle. If Kumen conveyed the woman’s offering into the hands of her missionary husband on the other side of the ocean, for example, he would find himself in Maurine Whipple’s Three Nephites story instead. “They Did Go Forth,”³ archetypical of the genre in source material, approach, and augmentation of its scope, is based on an account of healing at the hands of a mysterious stranger from Whipple’s own family history. She appended the transatlantic delivery of johnny cake for good measure.4

Neal Chandler’s “The Last Nephite” at first appears to take a very different approach than either Pace or Whipple.5 A comedic, modern-day encounter replete with corporate church trappings—hotels, business attire, security, files, corporate speak, and a general authority—the story even opens in the overflow of stake conference. A far cry from Zed’s night at the theater in Old New York, with oysters, wine, and cigarettes, a cultural hall may be the most immediate setting imaginable: the spare and unglamorous heart of the institution.

Like “American Trinity,” however, “The Last Nephite” leans into an association with those on the margins. Chandler’s protagonist, who inadvertently gets caught up in the orbit of one of the Nephites, speculates that it is perhaps his little heterodoxies that provoked the visitation in the first place—not because the Nephite viewed him as a sinner, but because he needed an accomplice. In both these stories, the Nephites demonstrate that they are not bound by the authority of the Church. Rather, they regard it with some cynicism, and inhabit a space uncomfortably outside of the very hierarchy that draws its legitimacy from what they represent.

Authority aside, it is not just the company the Nephites keep who resist our assumptions about orthodoxy and orthopraxy. Zed is not above evil-speaking of the Lord’s anointed—and not just any anointed, but Mormon himself. In Pace and Chandler, these special witnesses of The Book indulge in more than a little skepticism, alcohol, and polygamy. Simpson, the titular character in Levi Peterson’s “The Third Nephite,” is ugly, scrawny, foul-mouthed, wrathful, and most recently said to have been kicking around Las Vegas.6 Todd Robert Petersen’s Nathan Begay, a Three Nephites character in “Parables from the New World,” surprises a Mormon sheriff by lamenting that The Book of Mormon doesn’t contain tales like those about Old Man Coyote, who he suggests is gender non-conforming and into swinging.7

The tension between the inspiration, creation, and realization of a text is also a common thread in Three Nephites stories, diegetically and otherwise. Maurine Whipple enhanced hers for dramatic effect. Zed “made a point of infusing [The Book] with the requisite miracles.” Simpson is accused of living in a story book, and, as we’ve just observed, Nathan Begay has unexpected opinions about the ideal contents of scripture. Tim Wirkus’s The Infinite Future features three reclusive siblings caught between Brazil and Idaho, in a narrative compiled and translated from across many layers of nested accounts.8 These siblings—the Coopers—hide behind a heteronymous author they have invented named Eduard Salgado-MacKenzie. As with the Nephites, Salgado-MacKenzie is more talked about than seen, and primarily known by the trail of works he leaves behind. Like Zed, the Coopers are witnesses to and participants in the production of a lost, but revenant manuscript—Mackenzie’s novel, also entitled The Infinite Future. Though his book is not based on any real events (it’s pulpy Brazilian sci-fi), that is in no way an impediment to it becoming a sacred text to others, and it proves as capable of inducing a mystical experience as The Book of Mormon. Ultimately, what the three Coopers create survives their collective authorship and the compilation and translation process to take on a life of its own, becoming more real than the story of its origins.

This is why Zed spends so much time dropping in on Mormon to harangue him. As in the Gospel of John, Zed is acutely aware of the creative, animating power of the Word. When he claims that what he “was fighting Mormon for was nothing less than my existence, my identity,” it’s not a figure of speech. Again referring to his own embellishments of The Book during his time as scribe, Zed knows how much the text will shape not only how he is remembered, but how he remembers, and not just who he is perceived to be, but who he is. Though he frets that “The prophecies of my people needed to be real instead of just a beautiful literary device,” the danger or beauty of it is that they will end up being real no matter what.

Zed gives up the theater, but his inability to let go of his concern about the real leads him to seek out the Nephite god. Convinced that “the meaning of our lives has always been a construction,” he wants to reorient himself with the sole remaining, stable reference point available to him. Still, even he acknowledges that what he wants is not the same as what he needs. Though the sleeping Nephite god drops into the text like a deus ex machina, He doesn’t magically resolve anything. Zed finds him changed. Even He is not the constant Zed imagined Him to be. His wounds are healed. Their relationship has evolved: “I feel old enough to be the father of this sleeping god. That I have more to tell Him about His life than He can tell me about mine.” Asleep as He is, He is unable to grant Zed the words of release he seeks.

But Zed reaffirms his faith in The Book. Up until this point he has chiefly been concerned with the authority of writing the text. But he finds his faith again in its power as a tool for reading one’s life. The Book’s performative nature doesn’t flow in only one direction. Yes, when Zed does what The Book prophesies, he makes the prophecies true. When he remembers what was written in The Book, they become true memories. To some degree, he will always be subject to the Book’s construction. But the Word that was God is not bound by time or perspective. It runs in both directions. Even I AM— the most powerful performative utterance of all—needs someone to read it.

So, as Zed and Kumen disagree about the difference between remembering what Jesus’s directive was and what it was, Zed is onto something when he wonders about the possibility of redefining it later. If the life cycle of a text requires both author and reader, the reader’s interpretation wields the Word with as much power as the author’s. The constant isn’t the text itself, but the wrestle with it, which can play out in myriad different ways. Zed tells the Nephite god that he loved him precisely because “you read my heart.” And Zed recalls that the real danger of the Gadianton Robbers “was that there would be no record, no book to find oneself in.” So, he weeps for his fate, but returns to his ministry. Of all the different worlds he is wedged between, the two most prominent are the written text and how it is read.

What makes “American Trinity” a fitting synecdoche for American Trinity is that, by foregrounding such a profoundly Mormon trope as the Three Nephites, it reveals the inherently marginal nature of those whom Jesus chooses. This is a powerful affirmation of individuals on the periphery of the institutional church, perhaps even of their Mormon-ness. When Nathan Begay articulates the predicament of the Three Nephites, he references this lack of belonging, but also goes on to suggest how it is valuable to their calling: “I got one foot in each world, Sheriff. It makes people nervous. Hell, it makes me nervous. Except everybody’s caught between worlds, sheriff [sic]. Maybe it’s the only thing any of us got in common.”9

The fact that the Three Nephites can be drawn to people who, like themselves, are suspended between worlds is why they often succor those at death’s door. For example, in Pace’s novel Dream House on Golan Drive, Zed is called to watch over Riley Hartley, a Mormon who, at the end of his life, has long since lost his faith and forsaken the Church. Zed’s assignment is to “prevent Riley from approaching the veil prematurely.”10 Until Riley achieves some of the self-awareness that so torments Zed, until he can read himself and accept that he is more like his people than he thought, Zed cannot utter the words “Let him enter.” (Notably, returning to church activity is not a condition.) That this should finally occur in a subway car under the East River further corroborates the Three Nephites’ penchant for operating in the in-between. The Nephites’ other companion, the wandering Jew Ahasverus, or Verus, echoes Nathan when he remarks to Zed that Riley is “a lot like us, if you think about it . . . because he’s trapped, just like us.”11 But of course this doesn’t only refer to the end of Riley’s life—by then Zed had been shadowing him for a long, long time. As we’ve already seen, the thin edge between life and death isn’t the only place to suffer on the periphery.

The fact that the Three Nephites can be drawn to people who, like themselves, are suspended between worlds is why they often succor those at death’s door. For example, in Pace’s novel Dream House on Golan Drive, Zed is called to watch over Riley Hartley, a Mormon who, at the end of his life, has long since lost his faith and forsaken the Church. Zed’s assignment is to “prevent Riley from approaching the veil prematurely.”10 Until Riley achieves some of the self-awareness that so torments Zed, until he can read himself and accept that he is more like his people than he thought, Zed cannot utter the words “Let him enter.” (Notably, returning to church activity is not a condition.) That this should finally occur in a subway car under the East River further corroborates the Three Nephites’ penchant for operating in the in-between. The Nephites’ other companion, the wandering Jew Ahasverus, or Verus, echoes Nathan when he remarks to Zed that Riley is “a lot like us, if you think about it . . . because he’s trapped, just like us.”11 But of course this doesn’t only refer to the end of Riley’s life—by then Zed had been shadowing him for a long, long time. As we’ve already seen, the thin edge between life and death isn’t the only place to suffer on the periphery.

All the characters in the stories to follow have more than a few points in common with Riley Hartley, and the gay, cynical, carping, doubt-filled Zed is their patron saint. Since Zed is called to read the faith of the faithless, American Trinity may in fact best be understood as a collection of his wanderings and ministry. Zed’s constant interrogation of himself, his calling, and what is real is essential to his mission among those caught between worlds. Outside of “American Trinity” and Dream House on Golan Drive, he may not materialize in the text, but we can read him into it.

Ultimately, Zed’s wrestle with the reading of his own faith is his deepest expression of it, and the same can be said for everyone in this book. The details of each narrative are different, but, as Zed observes about the theater, the arc is familiar. Faith and unbelief, being in the world but not of it, being of the Church but not in it, orthodox and heterodox interpretations of a text—all Pace’s wanderers are caught up in this kind of tension. It can be as simple as the consequences of the philosophies of men, mingled with scripture, as in “Mormon Moment.” It can speak to the difficulties of living a divided existence, like the flight attendants (speaking of metaphors of not belonging) in “Robomaid” and “Flying Bishop.” At a parting of the waters in one’s life, it can take shape as the internal struggle between doing the hard thing and following the path of least resistance, as in “Sagarmatha.” Or it can manifest itself in a supernatural, apocalyptic event, like in the magical realist fantasia “Angels in Utah,” which sees names meant for proxy temple work resurrected to mortality and those intended to usher in immortality entombed instead.

“Lana Turner Has Collapsed!” also centers around the temple and the dynamic of inclusion and exclusion it inscribes on people’s lives. Gloria has fallen into inactivity because, since she and her husband have no children, she has never felt like they fit into the “celestial picture.” But when her husband returns to church and temple worship, she decides to give it a try as well, feeling a closeness to her mother as she prepares to do the temple work for the actress Lana Turner, in whom they shared an interest. But the experiment does not go according to plan, and Gloria discovers that she can’t find a place among the living by way of the dead.

In “Stairway to Heaven,” Jack Flanagan is neither alive nor dead. For as long as his body hasn’t been found, a sort of limbo reigns. In this interregnum, the narrator muses about alternate possible versions of Jack that might’ve taken a different path. He hopes for a “ram in the thicket” for Jack and his family, but perhaps he is looking at it the wrong way around: Jack’s death has sparked the narrator’s first earnest prayer, which plants the seed of a faith more nuanced and compassionate than what he’s experienced before. Perhaps the potential of alternate paths is for him. Alternate paths are also considered in “City of Saints,” which portrays a man from one City of Saints (New Orleans) who has moved to another (Salt Lake City) after being called to the Seventy. Conflicted between his own instincts and the expectations of his position, and still sensing the lingering presence of his recently deceased wife, he demonstrates how not all evolutions of faith result in an obvious change of course.

“Dreamcatcher” intersects with many of the themes in “American Trinity,” exploring the difficulties of handing down truth to the next generation, though by way of artistic and historical objects instead of the power of the text. Rell, a nightwatchman at a book depository, catches one of the dreams of his youth: coming face-to-face with the early Church and Book of Mormon relics that he had imagined would give him a perfect knowledge. But like most dreams, “It wasn’t what he thought it would be.” In a counterpoint between the Gilgal Sculpture Garden and a secret basement cache of all the Church’s most sacred artifacts, Rell discovers that, as in “American Trinity,” truth requires some active doing, and it’s not necessarily safe to make the effort. (This story also involves a curiously specific parallel with Peterson’s “The Third Nephite”—the juxtaposition of underwhelming relics with a bird falling down a chimney.)

In “Damascus Road,” backsliding Mormon Paul invites a stranded Jewish stranger named Saul to share his hotel room for a night. This encounter with his doppelgänger from another world prompts him to reevaluate whether he ought to go back to church and confess his sins or be less afraid of venturing into unfamiliar territory. On the flight home, he catches the eye of a missionary giving away a Book of Mormon across the aisle and—perhaps because of his recent encounter with Saul—finds the exclusivity of the young man’s message particularly grating. Turning away, he remembers a Russian poem he read in high school, which gives advice about what to do if one’s parachute does not open:

Spread your arms softly, like a bird,

And enfolding space, fly.

There is no way back, no time to go balmy,

And only one solution the simplest:

For the first time to compose yourself, and to fall

With the universal void in your embrace.12

Certainly, there is no better description of what it feels like to be caught between spheres than plummeting to where the sky meets the earth, where one has no choice but to cross from one life to the next. And, for the most part, the characters in this book embrace their lot, as the poet suggests. Not without fear, not without suffering, but, seeing that there is no way back, they accept the unknown to come.

Caliban revels may not last forever, but Zed is right to wonder about the when of Jesus’s promise that he and his companions will find “a fulness of joy.” He wants an end so desperately that he is named for it. But like too many texts involving Jesus, this one, too, “is maddeningly unclear.” So, all he can do in the meantime is give voice to the sorrow of his people—be they his lost immortal brethren, the descendants of Lehi, or the characters in this book. As Zed pours out his heart to the sleeping Nephite god, he takes credit for this passage in Jacob 7:26:

‘The time passed away with us, and also our lives passed away like as it were unto us a dream, we being a lonesome and a solemn people, wanderers, cast out from Jerusalem, born in tribulation, in a wilderness, and hated of our brethren . . . wherefore, we did mourn out our days.’ I made sure that passage survived. That was my work. So that there would be a record of how it was like for this people. Of how we read this life.

Similar to Zed’s own role in shaping The Book, some parts of this book began as non-fiction or have roots in real events. Others have been wholly invented. But they all convey the longing of those who are in some sense out of communion: lonesome, solemn, wandering, cast out, unrecognized by the Church or their own people. But they need not worry that there is no book that—transcending orthodoxy and disbelief— captures enough in-between-ness to find themselves in. David G. Pace has written it. That’s what you call the power of a text.

- William A. Wilson, “Freeways, Parking Lots, and Ice Cream Stands: The Three Nephites in Contemporary Society,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 21, no. 3 (Fall 1988): 13–25.

- Robert A. Rees, “The Midrashic Imagination and the Book of Mormon,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 44, no. 3 (Fall 2011): 55.

- Maurine Whipple, “They Did Go Forth,” in Bright Angels and Familiars: Contemporary Mormon Stories, ed. Eugene England, (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1992), 11–19.

- Veda Hale, Andrew Hall, and Lynne Larson,eds., A Craving for Beauty: The Collected Writings of Maurine Whipple, (Newburgh, IN: By Common Consent Press, 2020), 133.

- Neal Chandler, “The Last Nephite,” in Benediction: A Book of Stories (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1989), 166–94.

- Levi S. Peterson, “The Third Nephite,” in Night Soil: New Stories (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1990), 19–39.

- Todd Robert Petersen, “Parables from the New World,” in Long After Dark: Stories and a Novella (Provo, UT: Zarahemla Books, 2007), 49–58.

- Tim Wirkus, The Infinite Future (New York: Penguin Press, 2018).

- Petersen, 57.

- David G. Pace, Dream House on Golan Drive (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2015), 51.

- Ibid, 277.

- Yevgeny Vinokurov, “When the Parachute Does Not Open,” trans. Daniel Weissbort, Poetry CXXIV, no. 4 (July 1974): 190.

Christopher T. Lewis is Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of World Languages & Cultures at the University of Utah, where he teaches Brazilian Studies and, occasionally, Mormon Literature.

Christopher T. Lewis is Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of World Languages & Cultures at the University of Utah, where he teaches Brazilian Studies and, occasionally, Mormon Literature.

David G. Pace is a fiction and narrative non-fiction writer, journalist and editor. His debut novel, a coming-of-age story told with magical realism, is titled Dream House on Golan Drive (Signature Books, 2015). He is also a contributor to the collections Moth & Rust: Mormon Encounters with Death, Worth their Salt: Notable  but often Unnoted Women of Utah, Blossom as the Cliffrose, and The Path and The Gate: Mormon Short Fiction. His story “American Trinity” won an AML Short Fiction Award in 2011, and he was a finalist for the 2017 Barry Lopez Nonfiction Award. A long-time literary and performing arts critic and journalist, his articles, reviews and essays have appeared in the Christian Science Monitor, Huffington Post, American Theatre Magazine, Theater Week, 15 Bytes, Salt Lake Magazine, Salt Lake Tribune, Deseret News and elsewhere. His blog “The Little House We Dance In” focuses on literature, culture and politics.

but often Unnoted Women of Utah, Blossom as the Cliffrose, and The Path and The Gate: Mormon Short Fiction. His story “American Trinity” won an AML Short Fiction Award in 2011, and he was a finalist for the 2017 Barry Lopez Nonfiction Award. A long-time literary and performing arts critic and journalist, his articles, reviews and essays have appeared in the Christian Science Monitor, Huffington Post, American Theatre Magazine, Theater Week, 15 Bytes, Salt Lake Magazine, Salt Lake Tribune, Deseret News and elsewhere. His blog “The Little House We Dance In” focuses on literature, culture and politics.