I join with his many friends and family to mourn the recent passing of Thomas F. Rogers (1933-2024). Tom was a scholar and teacher of Russian literature, a playwright and an author of fiction and non-fiction, and a faith leader of great spiritual and intellectual depth and breadth. He valued charity and honesty to the extreme, and had a great impact on the lives of those lucky enough to spend time with him. This essay will focus on Tom’s literary contributions, particularly those that touched on his LDS faith.

I join with his many friends and family to mourn the recent passing of Thomas F. Rogers (1933-2024). Tom was a scholar and teacher of Russian literature, a playwright and an author of fiction and non-fiction, and a faith leader of great spiritual and intellectual depth and breadth. He valued charity and honesty to the extreme, and had a great impact on the lives of those lucky enough to spend time with him. This essay will focus on Tom’s literary contributions, particularly those that touched on his LDS faith.

For the details of his life, please see his official obituary. Briefly, he grew up in Salt Lake City, where he strongly felt the burden of his family’s relative poverty and the absence of his mentally ill father. He received a B.A. at the University of Utah, and served in the LDS North German Mission from 1955 to 1958. He married Merriam Dickson days after returning from his mission, and they would have seven children.

Tom attended the Yale School of Drama for two years, but then switched to a study of Russian, eventually earning a PhD in Russian language and literature at Georgetown University. From there, he received an appointment to teach at the University of Utah, where he taught for 3 years before being invited to join the BYU faculty. He spent the next 31 years teaching Russian language and literature at BYU. While there, he served for a time as director of the Honors Program. In the 1970s, Tom began writing plays, often with LDS characters and themes, that brought him attention as leading voice in Mormon literature.

I attended an BYU honors course on Tolstoy that Tom taught in 1987. It was a fantastic class, which required one of the largest sets of required reading I have ever seen: War and Peace, Anna Karenina, Resurrection, and many shorter works, all in one semester! It was in that class I met my future wife, Jenifer Larson. Jenifer tells me to say that she and other Russian majors were lucky to have the chance to study with such a non-dogmatic and thoughtful scholar (a fox rather than a hedgehog perhaps, to quote from an Isaiah Berlin essay by that Tom had all his students read).

The Slavic department was full of spiritual giants, including Tom, Gary Browning and Don Jarvis. The Church was well-positioned to have the three of them there, as they would serve as the first mission presidents in the former Soviet Union when those countries opened up to missionary work in 1990.

Tom and Merriam served as mission leaders in the Russia St. Petersburg Mission from 1993 to 1996. They later served in the Stockholm Sweden temple, assisting Russian church members who traveled to Sweden to receive their temple blessings. From 2007 until 2014, Tom was a traveling LDS patriarch assigned to Russia, Ukraine, Bulgaria, Armenia, Georgia, Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia. During his eight years serving in this capacity, he made 24 trans-Atlantic crossings and bestowed over 2600 patriarchal blessings.

In 1986, Eugene England wrote that Tom was “the best Mormon playwright, on the evidence of cumulative, consistent achievement.” However, Tom’s first significant play, Huebener, was not produced until he was 43 years old. Tom had studied playwriting at the University of Utah and under John Gassner at the Yale School of Drama in the 1950s, but none of his works from that period have been published. He later wrote, “[I created] uninspired scripts because I hadn’t yet connected my writing with my own psyche and truly fascinating Mormon concerns. In the meantime, I more fully discovered the profundity of Russian literature, which prompted me . . . to switch disciplines. I’ve never regretted it, though it cost me another six years in graduate school.” Of his draw to Russian classical literature, he wrote, “It was in an aesthetically intuitive way more than a rationally didactic discipline. It further underscored for me the universality of all human experience rather than its purported divisiveness, and it eventually served as the core subject matter I ended up teaching.”

In 1972, his first academic monograph, ‘Superfluous Men’ and the Post-Stalin ‘Thaw’: The Alienated Hero in Soviet Prose During the Decade 1953-1963 was published. An academic reviewer commented, “With the possible exception of hardened sociologists, most readers are likely to find Rogers’ monograph as difficult to read as the often turgid prose it analyzes.” Ouch! Another later monograph was Myth and Symbol in Soviet Fiction (The Edwin Mellen Press, 1992).

In 1972, his first academic monograph, ‘Superfluous Men’ and the Post-Stalin ‘Thaw’: The Alienated Hero in Soviet Prose During the Decade 1953-1963 was published. An academic reviewer commented, “With the possible exception of hardened sociologists, most readers are likely to find Rogers’ monograph as difficult to read as the often turgid prose it analyzes.” Ouch! Another later monograph was Myth and Symbol in Soviet Fiction (The Edwin Mellen Press, 1992).

Although Russian literature (and film) remained a passion throughout his life, Tom returned to playwriting in the mid-1970s, which he would call his “principal avocation.” As a missionary, he had served in Hamburg, the hometown of Helmuth Hübener, an LDS boy who in 1942, at the age of 17, was executed by the Nazi regime for producing anti-Nazi leaflets. Rogers wrote, “It was almost two decades later, as I served on the BYU faculty, that my colleague Alan Keele gave a presentation to our college faculty about Huebener’s impact on important post-war German authors, notably Nobel Prize winners Heinrich Böll and Günter Grass. Knowing of my interest in writing plays, Alan singled me out during the same lecture and challenged me to write a play on the subject. Alan and history professor Douglas Tobler were about to publish a book about it and generously shared their research, which became the play’s principal source. Till that moment I’d almost forgotten I’d ever written plays—so immersed had I meanwhile become in my career discipline, Russian literature. Alan’s unexpected challenge forcefully re-released the creative juices. The gracious interest and support just then of the BYU theater faculty was also an important catalyst.” (From Todd Compton, “A Playwright with a Passion for Unvarnished Deceptions: An Interview with Tom Rogers.”)

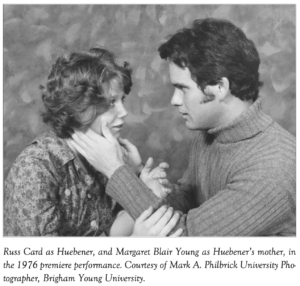

The debut run of Huebener was held at the Margetts Arena Theater, BYU, Provo Utah, in fall 1976. Tom wrote about the production, “I certainly didn’t expect the sensational response we got. As few plays ever do, it became a true “happening.” . . . For both the premiere performance and the anniversary of Helmuth’s execution, about a month later, we had intentionally rigged what proved to be an extremely dramatic “postscript.” After the initial applause, a line of three equally placed spotlights again lit the stage. In the first stood the real Karl-Heinz Schnibbe, in the third the real Ruddi Wobbe—Huebener’s two principal teenage LDS co-conspirators. The middle spot remained empty, commemorating Huebener’s own unavoidable absence. The effect was to bring events portrayed through artistic representation vividly into the audience’s awareness—almost into their laps in the tiny Margetts Arena Theater. . . . The effect was stunning, and word quickly spread. The play’s initial run was extended for a number of additional weeks, so that its small experimental theater venue (with a seating capacity for at most 250 persons) finally accommodated, by my estimate, an approximate 5,000 viewers. On the Monday of the final advertised week, students sat in long serpentine lines on the Fine Arts Building’s main floor, already queued to purchase the last batch of tickets, as normally happens only for athletic events at the Marriott Center.” Margaret Blair Young, then a student actor in the play, wrote a beautiful essay about the experience, “Doing Huebener”.

The debut run of Huebener was held at the Margetts Arena Theater, BYU, Provo Utah, in fall 1976. Tom wrote about the production, “I certainly didn’t expect the sensational response we got. As few plays ever do, it became a true “happening.” . . . For both the premiere performance and the anniversary of Helmuth’s execution, about a month later, we had intentionally rigged what proved to be an extremely dramatic “postscript.” After the initial applause, a line of three equally placed spotlights again lit the stage. In the first stood the real Karl-Heinz Schnibbe, in the third the real Ruddi Wobbe—Huebener’s two principal teenage LDS co-conspirators. The middle spot remained empty, commemorating Huebener’s own unavoidable absence. The effect was to bring events portrayed through artistic representation vividly into the audience’s awareness—almost into their laps in the tiny Margetts Arena Theater. . . . The effect was stunning, and word quickly spread. The play’s initial run was extended for a number of additional weeks, so that its small experimental theater venue (with a seating capacity for at most 250 persons) finally accommodated, by my estimate, an approximate 5,000 viewers. On the Monday of the final advertised week, students sat in long serpentine lines on the Fine Arts Building’s main floor, already queued to purchase the last batch of tickets, as normally happens only for athletic events at the Marriott Center.” Margaret Blair Young, then a student actor in the play, wrote a beautiful essay about the experience, “Doing Huebener”.

Douglas Alder, president of Dixie College, said in 1991 that “If one is allowed only a few experiences in life . . . one for me was watching the text emerge of Thomas Rogers’ play Huebener. The work is a product of our local culture which has universal meaning. The Huebener story presents a new challenge to Mormons. It invites all to consider models in addition to their pioneer legacy, to apply our thinking to contemporary issues, in this case the competing loyalty between freedom and obedience.” The author Orson Scott Card commented, “Huebener told us what no other Mormon play had reached . . . Huebener did what art is meant to do . . . We know more than a few artists who could die happy if they knew they had done that even once.”

However, the production also raised concerns, and Church leaders asked the BYU President to not allow future performances, and requested that a planned production in California not go forward. Tom recalled, “Glowing reviews in the Salt Lake newspapers apparently alerted certain General Authorities to possible unfavorable fallout affecting certain members and the Church’s welfare in distant places. I’ve never been sure why in 1976 we were asked to desist from further productions or publications on the subject. Some have speculated that it might have somehow interfered with plans to erect a temple behind the Iron Curtain in Freiberg, Germany . . . However, the timing doesn’t exactly coincide. We will never really know.” The ban was lifted after the fall of the Iron Curtain, and there was a revival production at BYU in 2000, as well as several other productions later in that decade.

However, the production also raised concerns, and Church leaders asked the BYU President to not allow future performances, and requested that a planned production in California not go forward. Tom recalled, “Glowing reviews in the Salt Lake newspapers apparently alerted certain General Authorities to possible unfavorable fallout affecting certain members and the Church’s welfare in distant places. I’ve never been sure why in 1976 we were asked to desist from further productions or publications on the subject. Some have speculated that it might have somehow interfered with plans to erect a temple behind the Iron Curtain in Freiberg, Germany . . . However, the timing doesn’t exactly coincide. We will never really know.” The ban was lifted after the fall of the Iron Curtain, and there was a revival production at BYU in 2000, as well as several other productions later in that decade.

Meanwhile, Tom wrote a second historical play, Fire in the Bones, a charitable portrayal of John D. Lee, one of the perpetrators of the Mountain Meadows Massacre, as a tragic figure. He based the details of Lee’s life on the writing of the historian Juanita Brooks. The dean of the College of Fine Arts and the chair of the Theater and Media Arts Department supported having a BYU production of Fire in the Bones, but the Academic Vice President convinced them that the presentation of polygamy, which played a major part in the play, would be taboo for the university. Instead, it was produced in 1978 by the short-lived Greenbriar Theater in Sandy, Utah, to little fanfare. Tom included it in all three of his published collections, giving only Huebener that same treatment. He later wrote, “Both of these plays suggest to what extent the rest of us are, in a collective setting prone to mob psychology and a far from ethical or spiritually sublime response to the ‘other’.”

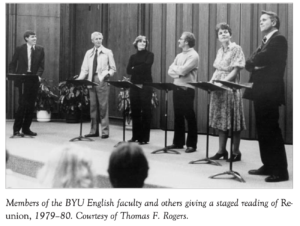

His next play, Reunion, was about a contemporary LDS family divided by conservative and liberal views of faith, and the children’s troubled relationship with their dying father. Tom later wrote, “[A] pattern of my innermost concern is the search for the father. This reflects very personally on my own terrible, terrible relationship with my own schizophrenic father. I could see where Huebener and Sander had that sort of relationship. John D. Lee had the same sort of thing with Brigham Young. There came a time when the father would not stand by his son anymore. In Reunion that is not the case, there is more of a positive betrayal there. But the pattern persists in my other plays.” In 1979, an on-campus readers’ theater production of Reunion was held, featuring Marden and Harlow Clark.

His next play, Reunion, was about a contemporary LDS family divided by conservative and liberal views of faith, and the children’s troubled relationship with their dying father. Tom later wrote, “[A] pattern of my innermost concern is the search for the father. This reflects very personally on my own terrible, terrible relationship with my own schizophrenic father. I could see where Huebener and Sander had that sort of relationship. John D. Lee had the same sort of thing with Brigham Young. There came a time when the father would not stand by his son anymore. In Reunion that is not the case, there is more of a positive betrayal there. But the pattern persists in my other plays.” In 1979, an on-campus readers’ theater production of Reunion was held, featuring Marden and Harlow Clark.

A fourth play, Journey to Golgotha (AKA God’s Fools) enjoyed a mainstage production at BYU’s Margetts Arena Theatre in fall 1982. Tom described it thusly, “This play addresses the plight of writers and religious dissidents in the USSR. Its characters are modeled after some of Russia’s greatest contemporary poets and religious martyrs—some purged by Stalin, some assassinated since World War II, and others still alive in Soviet prisons or residing, as emigres, in the West.”

A fourth play, Journey to Golgotha (AKA God’s Fools) enjoyed a mainstage production at BYU’s Margetts Arena Theatre in fall 1982. Tom described it thusly, “This play addresses the plight of writers and religious dissidents in the USSR. Its characters are modeled after some of Russia’s greatest contemporary poets and religious martyrs—some purged by Stalin, some assassinated since World War II, and others still alive in Soviet prisons or residing, as emigres, in the West.”

These first four plays were published as a collection in 1983 under the title God’s Fools: Plays of Mitigated Conscience. Originally published by Eden Hill, a short-lived independent publisher, a second edition was soon published by Signature Books. It won the 1982-83 Association for Mormon Letters Drama Award. The award citation read, “All of these plays center on two fundamental themes: the consequences of unrighteous dominion and our concomitant need for what Romans called ‘filial piety’. Rogers’s characters confront the necessity of making strong moral choices which, when made, will forever after alter relationships with individuals and institutions. Posing difficult questions and challenges, Rogers unshrinkingly probes the consequences of standing for Truth in a world of ambiguities.”

These first four plays were published as a collection in 1983 under the title God’s Fools: Plays of Mitigated Conscience. Originally published by Eden Hill, a short-lived independent publisher, a second edition was soon published by Signature Books. It won the 1982-83 Association for Mormon Letters Drama Award. The award citation read, “All of these plays center on two fundamental themes: the consequences of unrighteous dominion and our concomitant need for what Romans called ‘filial piety’. Rogers’s characters confront the necessity of making strong moral choices which, when made, will forever after alter relationships with individuals and institutions. Posing difficult questions and challenges, Rogers unshrinkingly probes the consequences of standing for Truth in a world of ambiguities.”

Eugene England reviewed the book in BYU Studies. “Rogers is an earnest man. Perhaps too earnest. The plays’ major fault is a persistent romanticism which, though far from insisting on a simple answer to life’s paradoxes as traditional or official LDS drama does, still wants the paradoxes laid out too neatly with characters providing too careful a balance of conservativism and liberalism, obedience and integrity, Russian and American absurdity and duplicity. The plays need more of the surprising, unpredictable complexity within people, as well as between them. But finally, Rogers’ earnestness is a fine resource. He is a seriously, naively religious man—as opposed to expediently, or traditionally, or wisely, or enthusiastically religious. He is one of God’s fools.”

In 1984, the BYU Department of Theatre and Media Arts began a new class, Playwrights’/Directors’/Actors’ Workshop (PDA), which workshopped class members’ original scripts. Tom participated as a playwright five times over the course of the 1980s and 1990s, trying out the plays Frere Lawrence (about the later life of T.E. Lawrence, 1984), Charades (a family struggles, Roshomon-style, to understand its Soviet past, 1986), Gentle Barbarian (a character study of the brilliant but morally flawed Russian author Ivan Turgenev, 1989), The Idiot (an adaption of the Dostoevsky novel with a Christ-figure “fool” at its center, 1991), and First Trump (about Utah’s Aiken lynching of 1857, which involved one of Tom’s ancestors, 1998). Recently, Tom wrote a novelized version of First Trump, which will be published in September by BCC Press as Desperate Measures. He also wrote several other theatrical adaptions of classic novels, including Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment and O’Conner’s A Good Man is Hard to Find, as well as adaptions of novels by local authors, such as historian Philip Flammar’s The Wager (of which there was at least a partial production at BYU, featuring Tom as a Russian soldier), and Benson Parkinson’s The MTC: Set Apart. Several of his Russian novel adaptions were performed in Russian by BYU’s Russian language students as a part of their course of study. He also acted in and directed many plays, including serving as the director of Eric Samuelsen’s 1993 family drama, Accommodations.

In 1984, the BYU Department of Theatre and Media Arts began a new class, Playwrights’/Directors’/Actors’ Workshop (PDA), which workshopped class members’ original scripts. Tom participated as a playwright five times over the course of the 1980s and 1990s, trying out the plays Frere Lawrence (about the later life of T.E. Lawrence, 1984), Charades (a family struggles, Roshomon-style, to understand its Soviet past, 1986), Gentle Barbarian (a character study of the brilliant but morally flawed Russian author Ivan Turgenev, 1989), The Idiot (an adaption of the Dostoevsky novel with a Christ-figure “fool” at its center, 1991), and First Trump (about Utah’s Aiken lynching of 1857, which involved one of Tom’s ancestors, 1998). Recently, Tom wrote a novelized version of First Trump, which will be published in September by BCC Press as Desperate Measures. He also wrote several other theatrical adaptions of classic novels, including Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment and O’Conner’s A Good Man is Hard to Find, as well as adaptions of novels by local authors, such as historian Philip Flammar’s The Wager (of which there was at least a partial production at BYU, featuring Tom as a Russian soldier), and Benson Parkinson’s The MTC: Set Apart. Several of his Russian novel adaptions were performed in Russian by BYU’s Russian language students as a part of their course of study. He also acted in and directed many plays, including serving as the director of Eric Samuelsen’s 1993 family drama, Accommodations.

Tom oversaw the publication of a second collection of plays, Huebener and other Plays, published by Robert Raleigh’s Poor Richard’s Publications in 1992. Besides Huebener and Fire in the Bones, it featured Frere Lawrence, Charades, and Gentle Barbarian. In 2017, Michael Perry’s Leicester Bay Theatricals published a three-volume series of Tom’s most significant plays. Volume 1, Perestroika and Glasnost, collects five plays about Russia, with an introduction by theater professor Bob Nelson. Volume 2, Personal Journeys, collects seven plays based on previous novels, plays, or historical figures, with an introduction by playwright Tim Slover. Volume 3, Crises of Faith, collects seven plays with LDS or Biblical characters and settings, with an introduction by playwright J. Scott Bronson.

Tom was also an author of notable fiction, poetry, and non-fiction essays. Three of his four published short stories, written from 1991 to 2003, were heavily autobiographical tales based on his relationship with his mentally ill father and his experiences as a missionary. His first LDS-focused non-fiction book was A Call to Russia: Glimpses of Missionary Life (BYU Studies, 1999). I wrote in a review, “Tom Rogers tells the story of his term as mission president in St. Petersburg as a collection of short reflections and anecdotes, in which he gives penetrating insights into his own soul, the strengths and failings in Russian society, what makes a good missionary, and the qualities that make Church organizations work. He writes with brutal honesty about his own failings, especially in his first months. It was revealing to see how the early months of a mission are full of many small embarrassments, foolish mistakes, and a general lack of comfort for the mission president as much as it is for the missionary. He includes the drudgery and disappointments of missionary work, including the guilt felt by himself and his missionaries because of their inability to help so many people they found drowning in alcoholism. Such discussion makes the joy over the miracles of the work, which he also details, that much stronger. The most satisfying parts are the loving descriptions of the wisdom and foolishness of local leaders working to create new Church units. A Call to Russia . . . is on the level of Eugene England’s best work in almost every way: intellectual depth, writing skill, and spiritual imagination. Many writers have one or two of those qualities, but few have all three.”

In 2016, the Neal A. Maxwell Institute published Let Your Hearts and Minds Expand: Reflections on Faith, Reason, Charity, and Beauty, a collection of thirty pieces of Tom’s writing, including essays, poems, reviews, personal letters, speeches, and journal entries, edited by Jonathan Langford and Linda Hunter Adams. Terryl Givens, in the introduction, wrote, “To study Tom’s essays, as readers will find, is to have one’s discipleship vigorously contested. His insights are no cheap palliative to the weary road warriors on the path to Zion . . . What sets Tom apart, in my mind, from a plethora of gifted LDS writers and cultural critics is the love and generosity that underlie his contributions to the discussion.”

Mahonri Stewart wrote in his Dialogue review, “As a book of short, religious, and academic non-fiction, Let Your Hearts and Minds Expand is extremely valuable to the Mormon intellectual community; but as a reflection of a devoted disciple and a soulful artist, it goes beyond even that to be authentically moving. In a modern world where spirituality and religious belief is a place of tension and contention, Rogers has written from his place of the faithful agitator—pushing our culture’s boundaries where needed and then turning around to help the Mormon community reach inward and pull the wagons around shared principles.” The book was given an AML Special Award for Religious Non-fiction Publishing. Also, Tom was given an AML Honorary Lifetime Membership in 2001.

I will miss Tom. He radiated love and concern for his students, but also held them to high standards. I’m glad that there are still are several of Tom’s essays and plays that I haven’t yet had the chance to enjoy. I can think of few things that will be better for my soul.

There will be a viewing on the evening of Friday, June 28th, from 6-8 pm. Another viewing will precede the funeral on Saturday, June 29th, starting at 9:30 am. The funeral will begin at 11:00 am. The address is: 1250 S Main St., Bountiful, UT.

Short fiction:

“Mormons Are Also People.” Sunstone, Summer 1977. (I don’t have access to a copy.)

“Hearts of the Fathers“, Dialogue, Summer 1991. A man and his wife struggle with having to institutionalize a mentally ill father.

“Pax Vobiscum.” Christmas for the World, 1991. Based on Tom’s experience of wanting to leave his mission, but being ministered to and convinced to stay by a wise zone leader.

“Another Death”, Dialogue, Winter 2003. Autobiographical story about a boy embarrassed by and brooding over his poverty, his father’s institutionalization in a mental hospital, and various personal failings.

Poetry

“Recognition,” “To Each His Own,” “Endurance,” “Oreos and Kool-Aid,” “Looking Back”. Sunstone, Summer 1977

“Limbs” Dialogue 14.2 (Summer 1981): 132-33.

Essays

Most are collected in Let Your Hearts and Minds Expand. Some that can be found online include:

“On the Importance of Doing Certain Mundane Things”. Sunstone, Dec. 1998.

‘Hooks’. Latter-day Saint Scholars Testify, 2009.

“‘A Climate Far and Fair’: Ecumenism and Abiding Faith“. Dialogue,

See also this tribute to Tom by Daniel C. Peterson. Dan and Tom were in the same Provo book discussion club as my parents for many years, I enjoyed listening in the few chances I had visiting Provo.

Thanks, Andrew!! Another LDS author whose work I look forward to exploring!!!

Tom’s enthusiasm was infectious, and he was always so generous with his time — answering emails with alacrity and substance. I once was there in his home for a cold reading of his play about T. E. Lawrence. I was there also for the awesome Hübner experience (including meeting Schnibbe and Wobbe), which filled me with pride for a young Latter-day Saint who cared more about principle than his own life.

Tom was a hero, and I expect him to continue his hero’s journey on the other side of the veil. I am sure that a cloud of Saints was there to greet his arrival.

Terryl Givens’ remarks, given at Tom’s funeral, are available here:

https://www.wayfaremagazine.org/p/no-referees-in-heaven

It is with a heavy heart that I have learned today of Thom’s recent passing. As a BYU student majoring in writing for film/theatre, Thom was a cherished, devoted mentor. Eugene England introduced me to Thom in the fall of 1981 after reading my first play, “Digger.” Enthusiastic about my play, Eugene asked if he could share it with Thom. Being new to LDS theatre, I, of course, said yes. A week later, I sat down with Thom in his office for the first time. I was immediately impressed by his openness, his willingness to think critically and “outside the box thinking,” as well as his commitment to the future of Mormon Drama–his deep-seated belief that the experiences of Latter-day Saints all of stripes, past and present, were the raw elements from which those possessing enough vision could create dramatic works with universal appeal. As I struggled to realize that belief in my own writing, Thom openly shared his frustrations with the setbacks he experienced as an LDS playwright, particularly those in the aftermath of the original production of “Hübner.” His enthusiastic endorsement of “Digger” meant so much to me–a convert to Mormonism who often felt more like a stranger than a fellow citizen among the Latter-day Saints. After graduating from the Y in 1984, Thom and I continued corresponding for nearly two decades. The inscribed copy of “A Call to Russia” that he sent me in 1999 is one of the most prized possessions on my bookshelf. More prized, however, are the encouragement, grace and unconditional love that came through in his letters over the years as I traveled the circuitous paths of my personal faith journey. Thank you, Thom–for your vision, your talent, your groundbreaking plays, and, most importantly, a life well-lived.