The following review contains detailed spoilers of the films Ordet (1955), Brigham City (2001), Heretic (2024), and Ronald’s Little Factory (2024).

Nearly twenty-five years since the release of God’s Army (2000), we are now well into a period of mainstream realism in regards to how Mormonism is depicted on the screen. Documentaries, fiction films, and television series made by Mormon, ex-Mormon, and non-Mormon filmmakers have by and large moved past tired stereotypes to depict Mormon characters of all stripes respectfully, sympathetically, and intelligently. Fantastic productions like Electrick Children (2012), Once I Was a Beehive (2015), Tokyo Vice (2022), Under the Banner of Heaven (2022), Mormon No More (2022), and now Heretic show a sensitivity and nuance with their Mormon subjects that rarely manifested in the ‘90s, when, for example, the film Orgazmo’s plot line of a naïve missionary acting in pornographic films to pay for his expensive temple wedding was one of the catalysts that prompted Richard Dutcher to make God’s Army in the first place. In fact, God’s Army’s biggest legacy may not be the Mormon filmmakers who it inspired but the steady integration of believable Mormon characters into films across the spectrum of belief. We still see the rare Mormon stock character with little depth beyond an infantile faith in the Church, but anyone claiming that cinema still generally treats Mormonism with disrespect hasn’t been paying attention—or actually seeing the films. Still, there has unfortunately been plenty of this rhetoric with Heretic, with several articles by people who haven’t seen it and even a statement from a Church spokesperson with the ridiculous assertion that the film actually “promotes violence against women because of their faith” (emphasis added), which seems exactly the opposite message from the film I saw.

In fact, with Heretic there seems to be two main debates circulating, particularly among Latter-day Saint commentators. The first is a rather surface-level debate about whether the film is accurate in its representation of Mormonism, and the second is a deeper discussion about whether the arguments the film’s antagonist presents against religion and faith in general are valid. In the end, I think that the film passes both questions with flying colors, although I don’t see it as either pro- or anti-religion as much as it is a testament to humanism—and humanity—as the most important value system available today. Despite this, it still cleverly leaves room for the miraculous or, in other words, the transcendent.

The question of how accurately cinema represents Mormonism began in earnest with A Victim of the Mormons in 1911 and has hardly abated since, so at this point everything that’s been said about Heretic misrepresenting the faith feels like the same things Mormons have said again and again from Victim and The Flower of the Mormon City (both 1911) up through The Secret Lives of Mormon Wives this year, with several hundred films and series in between. Essentially, those who object to these films don’t feel that their culture or their faith has been represented accurately or fairly; the subtext, particularly salient with reviews of Heretic, is that they feel the films in question are attempting to prove their faith system untrue at best or outright damaging or violent at worst. These arguments often resort to pointing out how the films haven’t even understood Mormon culture in the first place, so they cannot be trusted in their portrayals of the faith itself. Of course Mormons aren’t exclusive in this—right now the same conversation is happening, again, in Roman Catholic circles regarding the film The Conclave—but with Heretic, there have been many reviews that completely miss the mark in their critiques. They attempt to misrepresent the arguments of the antagonist Mr. Reed as oversimplified ramblings based on debunked “Jesus mythicist theory” or “neo-Campbellian spiels” that you would only see in obscure corners of the internet, not in respected academic circles. They see the film as a polemic against faith that fails due to the lackluster intellectual underpinnings of Mr. Reed’s arguments. Simultaneously, and ironically, other reviews by Mormons even read the film as ultimately supportive of LDS faith and belief.

I disagree with these analyses of the film, or at least think they’ve missed the broader picture. They’re flawed principally because they essentially attempt to debate with the fictional Mr. Reed directly rather than look at what the narrative of Heretic means in its entirety, beyond his diatribes. To be brief, I believe the co-writers and directors Scott Beck and Bryan Woods succeed in deconstructing the rationale behind faith in Mormonism or any other type of religion, and in proving their villain’s ultimate thesis, that the only “true religion”—or the fundamental characteristic of religion—is about control over its adherents. Of course, that’s only half the equation. Mr. Reed himself interprets this in a completley nihilistic way, believing it gives him himself permission to exercise that control, even through violence, and here the film disagrees with him, as the ultimate protagonist Sister Paxton learns to see past his sordid worldview to one where there is no need for religion, but that is filled with light and love rather than darkness and hate. I believe this film, grounded in the genre of body horror, actually makes an argument in favor of humanism, particularly in the context of how the film approaches Sister Paxton particularly and the evolution of her faith. This is complicated, however, by examining the ending and its foray into the transcendental style in film, or at least what that term from 1972 might mean today.

With this reading of the film, to me the least interesting thing about Heretic is Mr. Reed’s oral arguments, which is where most Mormon commentators have focused. I believe our varied responses have more to do with each writer’s preexisting beliefs about faith and religion than with the quality of his arguments themselves. For instance, his monologues within the film are often tepid and, as Sister Barnes shows as she spars with him, lacking in depth of analysis, but for me as a formerly practicing Mormon they resonated with my experience studying areas like comparative mythology, which took me years of reading and study to find truly compelling but which Mr. Reed only lightly touches on here in the confines of two-hour film. But rather than using this review to debate Mr. Reed’s arguments, what I find most fascinating about Heretic is that it allows for such a wide range of responses, for and against religion—the fact that it is prompting so many essays about Mr. Reed’s arguments is actually proof of its success. It’s provoking introspection and debate, proving that it’s not so much a polemic or a propaganda piece as an ambiguous narrative, allowing for different viewers to take away different messages.

At this point I’d like to give a quick plot summary for those who may want to read about the film without having seen it, though I’d like to reiterate the spoiler warning above. Heretic is about a companionship of missionaries named Sister Barnes and Sister Paxton who have an appointment with a potential investigator named Mr. Reed—these surnames are used throughout. With a rainstorm rising on Mr. Reed’s doorstep the sisters enter his home under the belief that his wife will be joining them (a realistic nod to actual mission rules), and, after a lengthy back and forth over issues like polygamy and revelation, Mr. Reed’s conduct begins to make them feel uneasy and want to leave. They’re locked in, however, and Mr. Reed draws them further into his mysterious home into a makeshift chapel with two doors which he labels with the words “belief” and “disbelief”—and one of which, he claims, leads out. There’s another long doctrinal/historical discussion—this one much more energetic and threatening—before they take the “belief” door and he entraps them in a basement dungeon. There, the film finally veers away from its heavy dialogue into more traditional horror film territory, and his arguments take a hard turn from disproving all religion to something more actionable, as he claims to have a real “prophet”—an old deathly woman in a white hooded robe—who can be resurrected after consuming poison. This appears to be true, to the missionaries’ horror, as the old hag apparently dies then comes back to life. Then, at the beginning of the third act, Mr. Reed slits Sister Barnes’ throat, killing her, after which the much more naïve Sister Paxton must use her own cunning to survive, even while he manipulates her down into a den full of these alleged “prophets” in cages—simply his victims. She manages to stab him, then later he stabs her, and in the final moments he asks her to pray for him, while crawling toward her to kill her. But as Sister Paxton prays, Sister Barnes comes back from death to deliver a killer blow across the side of his head with a piece of wood with three protruding nails. Having saved her companion, she slumps back into death and Sister Paxton finally finds a way out of the house.

All of this is frightening and quite gruesome, and may be particularly disconcerting for viewers who identify with the protagonists’ faith or gender. But it is precisely because those characters are portrayed so humanistically that it is effective—and I’m using the term humanism here to broadly refer to the value and potential of each human life, of our individual intellects and combined societies, rather than any specific historical philosophical movement. I’m thinking, for instance, of the humanism of a King Lear, naked and mad in the storm, asking, “Is man no more than this?” but having finally revealed his true nobility as a person after casting off all the trappings of his kingship. In this manner of just revealing the unique innate value of every individual, the concept of humanism in this film begins at the most fundamental level with how carefully the filmmakers created the characters of Sisters Barnes and Paxton, positioning them to maximize the viewer’s empathy toward them. Importantly, this doesn’t just mean Mormon or ex-Mormon viewers, but the film’s actual target audience of viewers with little to no preexisting knowledge of Mormonism, who may not be inclined to indulge such empathy like a Mormon viewer might.

To a large extent, nuanced portrayals of well-rounded characters who elicit the audience’s empathy is what I mean with the term “mainstream realism” for the best films made in the wake of God’s Army. The vast majority of the earliest depictions of Mormonism in film—essentially from 1911 to 1922—were based in nineteenth-century perceptions of the Church, casting Mormons as lecherous polygamists and ambushers of doomed wagon trains, with titles like Marriage or Death, The Mountain Meadows Massacre, The Mormon Maid, and Trapped by the Mormons. The United States’ Hays Production Code in the 1930s forbade “harmful” depictions of religion, resulting in largely sympathetic films like The Man from Utah (1934), Brigham Young (1940), Bad Bascomb (1946), Wagon Master (1950), Blood Arrow (1958), Jessi’s Girls (1975), and even Italian spaghetti westerns like They Call Me Trinity (1970). By the 1980s, however, the United States’ rating system combined with several high-profile instances of violence in various Mormon sects caused true-crime novels and made-for-TV films to begin showing the faith in a more sensational light. Thus, ever since the “escape from polygamy” film Child Bride of Short Creek in 1981 and the Gary Gilmore true-crime film The Executioner’s Song in 1982 there has been a slow but reliable procession of films in which Mormon characters have indulged in violence, extortion, abuse, and other untoward behavior; these are generally among the films to which real-life Mormons take issue, with good cause.

To a large extent, nuanced portrayals of well-rounded characters who elicit the audience’s empathy is what I mean with the term “mainstream realism” for the best films made in the wake of God’s Army. The vast majority of the earliest depictions of Mormonism in film—essentially from 1911 to 1922—were based in nineteenth-century perceptions of the Church, casting Mormons as lecherous polygamists and ambushers of doomed wagon trains, with titles like Marriage or Death, The Mountain Meadows Massacre, The Mormon Maid, and Trapped by the Mormons. The United States’ Hays Production Code in the 1930s forbade “harmful” depictions of religion, resulting in largely sympathetic films like The Man from Utah (1934), Brigham Young (1940), Bad Bascomb (1946), Wagon Master (1950), Blood Arrow (1958), Jessi’s Girls (1975), and even Italian spaghetti westerns like They Call Me Trinity (1970). By the 1980s, however, the United States’ rating system combined with several high-profile instances of violence in various Mormon sects caused true-crime novels and made-for-TV films to begin showing the faith in a more sensational light. Thus, ever since the “escape from polygamy” film Child Bride of Short Creek in 1981 and the Gary Gilmore true-crime film The Executioner’s Song in 1982 there has been a slow but reliable procession of films in which Mormon characters have indulged in violence, extortion, abuse, and other untoward behavior; these are generally among the films to which real-life Mormons take issue, with good cause.

In recent years many of these films and series with Mormon “villains” seem to be receiving greater attention than the 1980s’ movie of the week. Think of Missionary (2014), No Man’s Land (2017), Murder Among the Mormons (2021), Under the Banner of Heaven (2022), Keep Sweet (2022), Daughters of the Cult (2024), Mormon Mom Gone Wrong (2024), and the upcoming The Order, which, like the documentary No Man’s Land, is centered on real-life right-wing Mormon domestic terrorists. With such high-profile films, often with stars like Andrew Garfield and Hugh Grant, it’s easy to see why some Mormons feel like their religion is continually under assault from Hollywood.

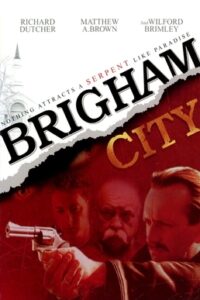

Heretic, however, is something different. Instead of being a film about victims of the Mormons, it’s part of a small cadre of recent films in which the Mormons themselves are victimized, particularly of kidnapping and hostage situations. The most obvious parallel, of course, is with The Saratov Approach (2013), a film based on a true story in which two missionaries in Russia were kidnapped and held for ransom in the 1990s. But there’s also The Cokeville Miracle (2015), about a hostage situation with children in a small-town Utah school, I Am Elizabeth Smart (2017), about her high-profile abduction, the documentary Tabloid (2010), about a missionary being kidnapped by his ex-girlfriend, and the upcoming fictionalized version of that story in The Manacled Mormon. One could also note that some of the Mormon characters are actually victims, not perpetrators, in Under the Banner of Heaven and Murder Among the Mormons. Of course I found myself thinking of The Saratov Approach frequently during Heretic, and the parallels are obvious—two frightened missionaries reason with their captor while facing the constant threat of violence and trying to engineer an escape. But once we reach the point where Mr. Reed actually kills Sister Barnes, the film which has the most in common with Heretic is Richard Dutcher’s second theatrical Mormon film Brigham City (2001), about a serial killer in a small Mormon town, and a film which is especially similar to Heretic in its ending.

I’ll come back to that, but my first point is that in all of these films the sympathy lies firmly with the Mormon characters. The films all work to make them well rounded beyond their shared faith, individualizing them through their imperfections. In Heretic this begins in the opening shot, long before the violence begins. In the first scene, Sister Paxton describes a faith-promoting experience she had while (accidentally?) watching a pornographic video. Again, some LDS writers have taken umbrage at this and how it breaks a major moral taboo and is thus supposedly inappropriate for a missionary character to speak about. But that may be precisely the point: this unexpected subject matter both humanizes the missionaries—they’re real Gen-Z young women, who have grown up in a world of online video and accessible pornography—and somewhat tenderly and comically depicts how their faith forms their entire worldview. It doesn’t make them unworthy or naïve, like a stereotypical character would be; it makes them real. This is followed by them questioning each other about their belief in God and not quite answering the question, setting up the entire confrontation with Mr. Reed later.

But more important to make the (non-Mormon) viewer identify sympathetically with these characters is the second scene, in which a group of teenagers pull down Sister Paxton’s skirt to briefly reveal her temple garments. She is hurt and flustered, crying in the next scene as they walk towards their appointment. Again, many Mormons are offended by the mere depiction of garments in a film, as they consider them holy and have covenanted to keep them private. As far as the film goes, however, this is a brilliant piece of writing, especially when you consider it from the non-Mormon viewer’s perspective. It takes the one thing that most people would consider weird and cultish about contemporary Mormonism—something that would make them not identify with the Mormon characters—and turns it into a reason to feel supportive and defensive of them. Sister Paxton’s embarrassment lets us know how important her garments are to her, and who she is as a person. From this point on, any viewer—even one who thinks garments are cultish and weird—is firmly in her corner, ready to be protective of her when she is much more seriously assaulted. The scene reminded me immediately of the opening of John Ford’s film Wagon Master, which dispells the taint of polygamy—Mormonism’s greatest taboo in the public mind when that film was made in 1950—by having the Mormon character immediately dismiss it, and the horns on his head, with a quick homesy and sarcastic joke about having “more wives than Solomon hisself.” Both films thus get the audience immediately sympathetic with the Mormons, and ready to root for them against the outside threats that emerge in both films to actually harm and even kill them.

That assault is not long in coming. Within minutes of entering Mr. Reed’s home, the sisters are barraged with questions that both require them to submit to his authority and fail to account for past Church practices like polygamy, which Sister Paxton ultimately admits she finds “pretty sketch.” Setting aside which side of the ongoing debate is ultimately correct, we can see what Mr. Reed’s long diatribes do to the two missionaries. Bit by bit they feel less in control and become unsure of points of their testimony that they had previously never questioned, like the nature of resurrection and the afterlife. There’s an ironic switch when the more worldly Sister Barnes insists they take the door labeled “belief,” while the more naïve Sister Paxton says they should just do what he wants and take the “disbelief” door. Ultimately they follow Sister Barnes, holding onto their testimonies through what’s now blind faith, but in the end it doesn’t matter because both stairways lead to the same room.

You can feel Sister Paxton’s faith fall apart through the murder of her companion and the increasing horrors of each level of the Inferno that is Mr. Paxton’s dungeon. Simultaneously, she stops putting as much faith in God, or even in the male missionary who has come looking for them, as in her own intellect. She comes to trust in and rely on herself. At one point as they return from the staircase Sister Paxton thinks the dead “prophet” has moved; Sister Barnes dismisses her and insists that she focus on their escape attempt. But after Sister Barnes is dead, Paxton returns to that thought, this time believing herself: the prophet did move, and the only explanation can not be a miracle—that she came back from the dead—so it must be that it was a second person, who removed the dead woman’s body and took her place. Again and again she begins understanding Mr. Reed’s deceptions, until at the very depths of his lair, surrounded by his obviously fraudulent “prophets” who he keeps in cages, she can see what he’s been arguing all along, that all religion is about control.

Only once she’s made this realization does she for the very first time exercise her agency to do something Mr. Reed does not expect: she stabs him in the throat while distracting him with a comment about her “magic underwear,” the very source of her embarrassment at the film’s outset. In the early scene, exposing her garments was a mortifying moment, but after passing through Mr. Reed’s gauntlet she is able to invoke the teenagers’ mocking words, which dismiss the garments’ sacredness, in order to lure Mr. Reed close enough so that she herself can defend herself, rather than relying on the protective power of the garments, a historical doctrine that Mormon belief still often ascribes to. In other words, she is now relying on herself rather than on God, and from this moment on she begins her assent up out of Mr. Reed’s house.

The film’s ultimate depiction of the power of humanity, rather than of God, comes at the climax. As Sister Paxton searches for a way out, Mr. Reed reappears and stabs her in the stomach—viewers may note that, indeed, he stabs her right through her garments, showing they have no actual protective power. With both of them crumpled and bleeding on the floor, Mr. Reed makes a bizarre demand, that Sister Paxton pray for him. She responds by saying that prayer doesn’t work, citing a medical study which found that there is no connection between prayers and medical outcomes. This bit of medical and social science data seems rather out of place in a young missionary’s mouth, but she then expands on it by saying that even if there is no God who answers prayers, it’s still beautiful for people to pray for each other. And she begins to pray for Mr. Reed, even as he crawls toward her to finally murder her. This moment shows that she hasn’t merely lost her faith in God, being left with nothing as Mr. Reed purposed, but she shifted it to a faith in humanity—a true love for each other. Thus she sheds the last remnants of her Mormon identity, becoming the heretic of the film’s title, but one who embraces the beauty of mankind—praying for each other—without the need for any divine intercessor. Ironically—and importantly—this is the moment when she becomes most Christlike, loving her enemies and praying for those who persecute her.

When she is able to do this, to accept all of humanity as already perfected and without need for an atonement or resurrection—and even pray for Mr. Reed, the worst of what humanity has to offer—then she quickly is freed from his grasp. He dies and she recovers enough strength to once again use her memory and her wits to find her way out. She stumbles out into the white morning light, having freed herself from his physical, pretend, windowless church only after freeing herself from her own mental, pretend, windowless church, her escape from faith in God immediately preceding her escape from Mr. Reed. Early in their lesson she had said that she hopes to be reincarnated as a butterfly so that she can land on the hands of her friends and let them know she still loves them, a most undoctrinal wish from a devout Mormon perspective. Now, liberated and outside, a butterfly does indeed land on her hand, a symbol either of Sister Barnes’ spirit coming to visit her, or of her own spiritual death and rebirth that she has just experienced—or both.

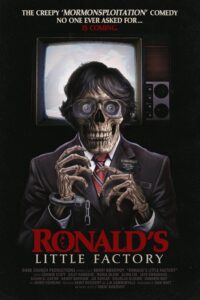

Heretic has gained the lion’s share of attention lately, but it’s not the only new film about a young Mormon trapped in a dangerous situation he can’t escape from. In recent weeks Utah-based director Brent Bokovoy premiered his film Ronald’s Little Factory in screenings at various Salt Lake City theaters; it will be available on Amazon and other platforms by the end of the year. Bokovoy is a former member of the Church and envisioned his film as a way to help other former members deal with some of the trauma that Church membership may have caused, particularly Mormonism’s purity culture of guilt, shame, and strict control over sexuality. The film’s title comes from a well-known 1976 general conference sermon by Boyd K. Packer, in which he compared genitalia to “little factories” with their capacity to produce life, with the admonition to avoid masturbation and wait for marriage for any type of sexual activity.

Heretic has gained the lion’s share of attention lately, but it’s not the only new film about a young Mormon trapped in a dangerous situation he can’t escape from. In recent weeks Utah-based director Brent Bokovoy premiered his film Ronald’s Little Factory in screenings at various Salt Lake City theaters; it will be available on Amazon and other platforms by the end of the year. Bokovoy is a former member of the Church and envisioned his film as a way to help other former members deal with some of the trauma that Church membership may have caused, particularly Mormonism’s purity culture of guilt, shame, and strict control over sexuality. The film’s title comes from a well-known 1976 general conference sermon by Boyd K. Packer, in which he compared genitalia to “little factories” with their capacity to produce life, with the admonition to avoid masturbation and wait for marriage for any type of sexual activity.

Tonally the film could not be more different from Heretic: it’s an over-the-top comedy, purposefully overacted with stylized performances to match the stylized production design, making it reminiscent of Trent Harris’s post-Mormon sci-fi comedy Plan 10 from Outer Space (1995). Smartly, Bokovoy sets the film in the 1970s, when Packer’s sermon was new. The plot centers around a young man named Ronald the night before he is set to leave on his mission. Haunted by Packer’s talk, he handcuffs himself to his bed’s headboard in order to avoid masturbating and remain worthy to serve a mission. He apparently succeeds in this, but the next morning his mother is mortified and throws the handcuff key out the window, never to be seen again. Thus Ronald is cuffed to his bed while a procession of people, particularly his overbearing mother and her ward Relief Society president, come through his room to berate him, pray for him, or attempt increasingly desparate ways to free him from the bed, all while a clock ticks down to the moment he’s supposed to leave on his mission. His father, a cop who carries a loaded gun, is treated as a threat throughout the film, and he only appears once, in a scene in which he threatens Ronald with death if he ever finds out he is sexually impure. This of course is derived from a statement by Spencer W. Kimball in his 1969 book The Miracle of Forgiveness, that it “is better to die in defending one’s virtue than to live having lost it without a struggle.”

While Ronald’s Little Factory is played primarily for laughs, this threat of what is essentially blood atonement lies at the heart of the film’s critique of Mormonism’s purity culture. And it is, of course, also the central point of the climax of Richard Dutcher’s third film States of Grace, in which a missionary attempts suicide after having sex with a neighbor, precisely, as with Ronald’s Little Factory, because his overbearing father has convinced him that he is now better off dead. Even the most devout Latter-day Saints can identify aspects of Mormon culture like this which seem to fully verify Mr. Reed’s assertion that religion is about control. Though the tone is completely different, both Ronald and Sister Paxton are in essentially the same position, and they progress through it in a similar fashion. They are both trapped in a house that symbolizes the church, and they both have to lose their faith in that church in order to gain the strength and confidence to fight their way out.

For Ronald, he sees how his ward community values obedience and purity more than his own well-being, or even his own intrinsic worth as a human being. He begins hallucinating nightmare visions of Elder Packer stalking him down the hallway like a zombie. At the climax, unable to free himself from his handcuffs, he instead removes the entire headboard and fights his way out of the house and his gated community to the bright light and fresh desert air that lays beyond. The closing shot is a near match of Sister Paxton in her liberation: both have found their way out of their faith and their abusers’ control into the clear light of freedom and autonomy. Both are panting for breath and are wounded from their attempt—Sister Paxton with her stab wound and Ronald dragging along his bed—but both are amazed to finally be free.

If we can see both Heretic and Ronald’s Little Factory as metaphors for liberation from organized religion, there is still one important point that I haven’t yet discussed, and which many readers may have already noted. Sister Paxton does not simply defeat Mr. Reed by herself or through her own autonomy. Instead, Sister Barnes defeats Mr. Reed when she hits him on the side of the head with the rotting board. Barnes, however, has been dead for the entire third act of the film. There is a tradition in horror films of characters seemingly coming back from the dead for a last-second confrontation, but this seems unlikely given how long she’s laid there and how thoroughly Mr. Reed has probed her body with his blade. So this apparently is not her reviving from a temporary death—it is an actual resurrection. In other words, Sister Paxton is saved by a miracle.

This moment, while easily anticipated on a narrative level—the rotting board is quite flagrantly set up as a potential weapon, hidden from Mr. Reed, earlier in the film—tremendously complicates Heretic as a testament to humanism and nothing else. And herein lies much of the film’s ambiguity: is this a divine miracle from God, or a “humanist” one—an inexplicable moment that happened out of something like Sister Paxton’s love for and belief in her fellow men? Or does it represent the power of Sister Barnes and her commitment to saving her companion? After all, earlier Sister Barnes relates a story about when she as a young girl did actually die and was brought back to life by the doctors treating her. So she’s already returned from death once without divine intervention—could she have done it again?

The film, to its credit, doesn’t answer this, but it was this moment that reminded me of The Transcendental Style in Film. This was a 1972 book by Paul Schrader, who quickly went on to be a regular screenwriter for Martin Scorsese, penning films like Taxi Driver (1976) and Raging Bull (1980), before writing and directing his own films, up to the present. Throughout his career Schrader has been interested in issues like faith, grace, and redemption, and in this early book he analyzes the films of the directors Carl Dreyer from Denmark, Yasujiro Ozu from Japan, and Robert Bresson from France to see how they have created moments of “transcendence” in their films. That of course is a somewhat vague term, which is precisely why it might be more useful to describe something like Sister Barnes’ resurrection: the connotations of the term “miracle” might be too restrictive, particularly in a religious sense, to describe an event which is not necessarily religious. But we can certainly all agree that the moment is transcendent.

To be extremely reductive in summarizing the book, Schrader finds stylistic and structural similarities in all three directors’ works. First is a foregrounding of the banal, quotidien, or the “everyday”—the visual style can appear blank or flattened out; the actors, particularly in Bresson’s films, can give equally flattened performances, exhibiting little human agency at all, acting more as automatons with no psychological motivation; the films can feel increasingly sparse or claustrophobic as we move towards the climax, as though the world, at least emotionally, is closing in. Then when things are at their bleakest, stylistically or narratively, there is a moment of abundance: something powerful and beautiful erupts on the screen. After having all of our emotions stripped away for ninety minutes, there is an unreservedly emotional release, and this moment can be a revelation of the transcendent.

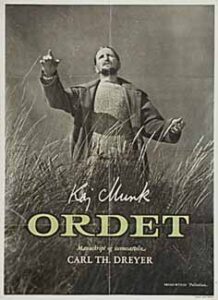

Carl Dreyer’s 1955 masterpiece Ordet, which means “the Word” in Danish, is an imprecise example of the transcendental style but a provocative precursor to the climax of Heretic. The film is a chamber drama about a family of a widowed patriarch, his three adult sons, and the pregnant wife of the eldest son. Much of the action centers around the banal events of the youngest son courting a local barmaid and the theological differences keeping the two families apart. This is merely a distraction, however, from the main conflict of the film, between the oldest brother Mikkel, who has completely lost his faith, and the middle brother Johannes, who has gone insane and now believes he is Jesus Christ. He wanders the endless fields of Jutland, preaching to the grass and causing embarrassment to the family. Mikkel even sees his condition as what will happen to anyone who studies religion too fervently. The film’s events are interrupted when Mikkel’s wife Inger goes into labor. The baby dies, and Inger herself dies soon after, leaving the family, particularly Mikkel, completely broken. During her wake, however, Johannes wanders in and, prompted by Mikkel and Inger’s surviving daughter, asks God to raise Inger from the dead. She immediately comes back to life, sits up, and embraces her husband, who has rediscovered his faith.

Carl Dreyer’s 1955 masterpiece Ordet, which means “the Word” in Danish, is an imprecise example of the transcendental style but a provocative precursor to the climax of Heretic. The film is a chamber drama about a family of a widowed patriarch, his three adult sons, and the pregnant wife of the eldest son. Much of the action centers around the banal events of the youngest son courting a local barmaid and the theological differences keeping the two families apart. This is merely a distraction, however, from the main conflict of the film, between the oldest brother Mikkel, who has completely lost his faith, and the middle brother Johannes, who has gone insane and now believes he is Jesus Christ. He wanders the endless fields of Jutland, preaching to the grass and causing embarrassment to the family. Mikkel even sees his condition as what will happen to anyone who studies religion too fervently. The film’s events are interrupted when Mikkel’s wife Inger goes into labor. The baby dies, and Inger herself dies soon after, leaving the family, particularly Mikkel, completely broken. During her wake, however, Johannes wanders in and, prompted by Mikkel and Inger’s surviving daughter, asks God to raise Inger from the dead. She immediately comes back to life, sits up, and embraces her husband, who has rediscovered his faith.

The madman raising the dead at the behest of a child is an obvious moment of transcendence, particularly in how Dreyer films the moment of Inger’s resurrection, with not somber amazement but her passionate and very physical kiss with her husband. Conversely, in the tradition of horror films, Sister Barnes’ resurrection happens off screen, so that we first see her blow to Mr. Reed before we see her standing over him. While her return to life is a shock, when we do see her it’s not as a triumphant vanquisher, full of life and vitality like Inger, but as someone who is bloodied and broken, ready to collapse. Visually, therefore, this may not read as a transcendent moment, but narratively, in the context of Sister Paxton’s prayer, it certainly is.

Up to this point in the film, never once have the missionaries suggested saying a prayer. This began to annoy me as I watched and chalked it up as one of the film’s cultural missteps, because as a returned missionary myself I believe that real LDS missionaries would have said several prayers for assistance throughout such an ordeal. So the lack of prayer felt like something the filmmakers got wrong. But at the point when Sister Paxton does begin praying it became obvious that this was a specific narrative choice. By not having their missionaries seek divine intervention, Beck and Woods are following the tradition of the transcendental style, cutting the characters off from anything divine as they sink increasingly into the banal darkness of Mr. Reed’s prison. Their options for alternative actions become equally limited. To be sure, Sister Paxton’s belief in her own ability to rectify her physical peril has steadily grown, and when she finally reaches the point where her faith in mankind replaces her faith in God, only then is she finally able to truly pray. She prays not to God, but to—and for—each other, including her dead companion. This is the moment, like the girl putting Johannes’ hand on her dead mother, that allows the miracle, the transcendent moment, to occur. It initially occurs in several quick shots of violence, of course, but after Mr. Reed is dead we hold on his moment for a tenderly long moment, as the companions are given time to rest, commune together, and bask in their strengthened connection. While Sister Barnes slips back into death, Paxton holds her in her arms in what is virtually a pietá: Sister Barnes, like Christ, returned from the dead to save her wounded friend. This utterly beautiful shot is Heretic’s version of Ordet’s kiss—a physical, corporeal connection between two people who love each other, and a truly humanistic interpretation of what a great transcendent moment can be.

It is also through this human connection after the end of the violence that Heretic has its strongest connection with Brigham City. In that film the sheriff and bishop Wes is haunted by the question of who in his small town could be responsible for the string of murders that is terrorizing the community. Initially communal and trusting of each other, the town begins getting torn apart, ravaged with doubt and suspicion about everyone there, from the outsider FBI agents to the people sitting on the pew next to them. This is a dissolution of faith in humanity, and, as with Mr. Reed’s mental tortures, there is nothing there to replace it but darkness. In the end, Wes discovers that the murderer is his own deputy, someone he himself had brought into the community and, up until the end, the only person he had trusted intrinsically. He is forced to shoot him, and his faith in both God and his fellow men is shattered. Everything has been stripped away.

It is also through this human connection after the end of the violence that Heretic has its strongest connection with Brigham City. In that film the sheriff and bishop Wes is haunted by the question of who in his small town could be responsible for the string of murders that is terrorizing the community. Initially communal and trusting of each other, the town begins getting torn apart, ravaged with doubt and suspicion about everyone there, from the outsider FBI agents to the people sitting on the pew next to them. This is a dissolution of faith in humanity, and, as with Mr. Reed’s mental tortures, there is nothing there to replace it but darkness. In the end, Wes discovers that the murderer is his own deputy, someone he himself had brought into the community and, up until the end, the only person he had trusted intrinsically. He is forced to shoot him, and his faith in both God and his fellow men is shattered. Everything has been stripped away.

At the climactic LDS sacrament meeting the next day, however, Dutcher turns from that darkest moment to give the audience a moment of transcendence. Feeling guilty and faithless after his experience, Wes—now acting as the bishop—declines to take the bread of the sacrament. As Mormons know, this is an unusual and socially uncomfortable act which generally indicates that the person believes they are unrepentant and unworthy to partake of the sacrament and have their sins forgiven. As the bishop, who always takes the sacrament first while, essentially, the entire ward watches, this is an even more extreme act for Wes to take. But then the miracle occurs: first his counselor sitting next to him, whose daughter was killed, refuses the bread also. Then, as the young men pass their trays silently around the chapel, every single person refuses to partake, an act of a community healing and solidarity, literally coming back together after they have been so violently torn apart. A confused young deacon returns to Wes, who now sees himself and his ward family for what they are—imperfect, wounded, but loving and faithful to each other as humans and friends. Sobbing, he now takes the bread, and as everyone else follows suit the entire congregation begins to find peace.

This transcendental ending implies a healing with God as well as with humanity, and this may be true for Sister Paxton’s transcendental moment as well. What both films have in common is the connection between the characters: Wes is surrounded by people who forgive him and love him, and Sister Paxton holds Sister Barnes in her arms. After Paxton’s encounter with the teen girls, Sister Barnes reassures her that she’s a cool, good person, and we see the flicker of the beginning of a bond between them. Now, as Sister Barnes slips away and the butterfly returns to land on Sister Paxton’s hand, we feel that they, like Wes’s ward members, are truly united through the closest bond for the rest of Sister Paxton’s life—or perhaps through all eternity.

At the end of the day, Heretic has a beautiful ending precisely because it can be seen in so many different ways. Whether we find it faith promoting or not, or whether we believe that Paxton, like Ronald, has found peace by escaping from the church and losing her faith or, like Wes, by returning to the heart of the church and finding her faith, we can hopefully all agree that she has found peace. The film may or may not be a testament to the power of God, but, like Brigham City and even Ordet, it is a testament to the power of human connection. Viewers will take what they want from Heretic and these other films, but examined together they show a powerful avenue for future Mormon films to explore.

Randy Astle is the author of Mormon Cinema: Origins to 1952 and over sixty articles on Mormon film. He has taught Mormon cinema at Brigham Young University, acquired hundreds of DVDs as the BYU library’s Mormon Film Specialist, edited special issues of BYU Studies and Mormon Artist magazine, served two years as film editor for the AML’s journal Irreantum, programmed film screenings at the Sunstone Summer Symposium, and created the annual academic forum at the LDS Film Festival. He received the Mormon History Association and B. H. Roberts Foundation Research Grant in 2023 and an award for criticism from the AML in 2008 and 2019. He is currently writing a second book, Mormon Cinema: 1953 to 2024.

Randy Astle is the author of Mormon Cinema: Origins to 1952 and over sixty articles on Mormon film. He has taught Mormon cinema at Brigham Young University, acquired hundreds of DVDs as the BYU library’s Mormon Film Specialist, edited special issues of BYU Studies and Mormon Artist magazine, served two years as film editor for the AML’s journal Irreantum, programmed film screenings at the Sunstone Summer Symposium, and created the annual academic forum at the LDS Film Festival. He received the Mormon History Association and B. H. Roberts Foundation Research Grant in 2023 and an award for criticism from the AML in 2008 and 2019. He is currently writing a second book, Mormon Cinema: 1953 to 2024.