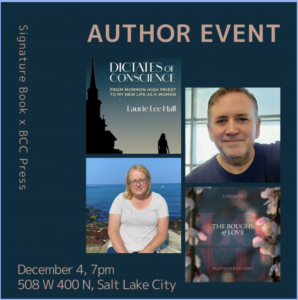

Nathan Kitchen introduces his new memoir, The Boughs of Love: Navigating the Queer Latter-day Saint Experience During an Ongoing Restoration, which was published by BCC Press earlier this month.

Nathan Kitchen introduces his new memoir, The Boughs of Love: Navigating the Queer Latter-day Saint Experience During an Ongoing Restoration, which was published by BCC Press earlier this month.

I am one of the last members of the generation of Latter-day Saint young men officially taught, as a matter of policy, to get married to a woman as a remedy to overcome “homosexual inclinations.” I did not come to understand this until I was president of Affirmation: LGBTQ Mormons, Families & Friends, and had a bird’s eye view of all the activity that had been going on in the queer/Latter-day Saint intersection over the history of the modern church.

If we mark time according to Greg Prince’s premise in David O. McKay and the Rise of Modern Mormonism, the David O. McKay presidency marks the beginning of the modern church. This rise coincided with the rise of today’s LGBTQ civil rights movement. The ideas that underpin the word “modern” and the word “movement” make both the modern church and the LGBTQ civil rights movement social siblings who have grown up side by side. Although these siblings have now been in a long-term relationship of seventy-plus years—tirelessly meeting each other in the public square, the ballot box, city councils, legislatures, and even the courts—public engagement on an external social and political playing field is not what makes this relationship interesting. The heart of the story lies in the complex and evolving relationship between the modern church and its own queer population.

Although the modern church is really good at telling its part of the story in this relationship, it forcefully attempts to tell the story of queer people also. In the matter of the queer/Latter-day Saint intersection, the modern church may own the terms of “belonging,” but the queer children of God own the intersection. It is ours to navigate, talk about, and assign meaning to according to our experiences there. And this is exactly what I do in my memoir. I take the responsibility of intersection ownership seriously, and in so doing, the story of the beloved queer children of God shines through with the light of ten thousand sacred groves.

We need more of this. We need the entire tapestry of stories and experiences of queer people who are part of the great houses of Zion, gathered up into the boughs of their family trees in love. We need the hope of a Waters of Mormon ecclesia who will insist on nothing less than the realization of the best parts of our Mormon theology concerning equity and justice (3 Nephi 6:4), inclusive eternal families, and exaltation for their authentically queer children and neighbors.

LGBTQ Mormons exist autonomously in a global network of mentors and peers. Within this worldwide connection, we support one another as we navigate the ecosystem of our spiritual home as well as our personal intersection with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. As sexual and gender minorities, we often operate unseen in the margins. My memoir aims to correct this tendency for queer Mormons to be unseen, so I speak unashamedly and objectively about the experiences of queer Latter-day Saints, shine a light on the intersection, and then inspire hope and queer joy. Within its pages, you will follow my journey as I sit in the boughs of the cherry trees that surrounded my childhood home as a young boy through the conclusion of my four years as president of Affirmation, standing for my peers in the queer/Latter-day Saint intersection as I built communities of safety, love, and hope. As president of Affirmation, I have seen the queer/Latter-day Saint intersection from a vantage point not many get to experience. My peers elected me to this unique position, and it is my duty to be a reliable reporter of my experiences there. Therefore, I pull back the curtain and speak about the inner workings, concerns, and decisions within this beloved global network of LGBTQ Mormons.

How I go about doing this will cause divine discomfort as I advance a narrative that boldly stretches the familiar theology of Mormonism in ways that account for the lived experiences of the queer children of God. In so doing, it challenges the current dominant narrative in the Church about what constitutes an acceptable queer in the kingdom. This exercise does not ask queer people to stay in a system that does not feel safe or healthy for them. In the face of intimidating prejudice, harassment, and discrimination in our spiritual home, personal revelation allows each queer person to walk the path of joy and progression that God has laid out for them. In the end, the Church will need to run to come find us, as did the apostles towards Joseph of Arimathea’s tomb on resurrection morning. In all its running, let the ongoing restoration catch up to us!

One of the reasons I chose to publish my memoir with BCC Press is its stated aim to “encourage faith in Christ.” For many of my readers, this may be the first time they encounter a queer-centric, Christ-centered text. Currently, in the Church, those two items are seen as incompatible and cast as polar opposites in the household of faith. No! In a full-bodied faith, we must be just as comfortable with the table-flipping Jesus as we are at his feet, listening to the Sermon on the Mount. You can be a queer person of faith and still explore the harms and prejudice of your spiritual home. You can affirm another’s testimony and faith without it threatening your own beliefs or invalidating your own experiences. Faith, after all, is not only “the principle of action, but of power also, in all intelligent beings, whether in heaven or on earth (Lectures on Faith 1:13).” This is the faith that Christ demonstrated, and that I practice when I consider the queer children of God.

One of the reasons I chose to publish my memoir with BCC Press is its stated aim to “encourage faith in Christ.” For many of my readers, this may be the first time they encounter a queer-centric, Christ-centered text. Currently, in the Church, those two items are seen as incompatible and cast as polar opposites in the household of faith. No! In a full-bodied faith, we must be just as comfortable with the table-flipping Jesus as we are at his feet, listening to the Sermon on the Mount. You can be a queer person of faith and still explore the harms and prejudice of your spiritual home. You can affirm another’s testimony and faith without it threatening your own beliefs or invalidating your own experiences. Faith, after all, is not only “the principle of action, but of power also, in all intelligent beings, whether in heaven or on earth (Lectures on Faith 1:13).” This is the faith that Christ demonstrated, and that I practice when I consider the queer children of God.

And now we come to the reason why I wrote The Boughs of Love. Jim Downs penned one of my favorite short but smart analyses of the gay liberation movement. He illustrates that one of the most significant outcomes of the movement was not marches and rights but a sophisticated intellectual transformation in the ways LGBTQ people thought about themselves, power, and oppression. As a community, we were writing ourselves into existence. He concludes, “Beneath and before the street protests and parades of gay liberation lay this intellectual revolution. It was a deep and laborious engagement with ideas and ideologies that made LGBT people advance liberation. In many cases, this revolution led LGBT people to retreat from political confrontations with governmental authorities and from talking about rights. Instead, they used tremendous energies to develop communities and cultivate a culture of their own. The efforts to write about LGBT history was one powerful expenditure of their political capital, talents, resources and intellect. Its goal was not exclusively to change how those in power or in larger society defined them: it was to provide the LGBT community with a sense of their own considerable cultural heritage and legacy.” (https://aeon.co/essays/the-radical-roots-of-gay-liberation-are-being-overlooked)

While president of Affirmation, I was using my tremendous energies to build communities and cultivate a queer Latter-day Saint heritage. Now, thanks to BCC Press, I have the opportunity to write about this moment in history. Downs’ observation about writing LGBTQ history is, in a way, how I feel about my memoir. It is not a work to change how those in power, society, or even my fellow non-queer Latter-day Saints define me or queer Latter-day Saints. I have written this book to lift the chin of my queer peers who are and were navigating the queer/Latter-day Saint intersection and provide this beloved community with a sense of their own considerable cultural heritage and legacy.

As you read my memoir, keep this in the back of your mind: Queer is queer. Queer is provocative. It doesn’t matter how many spoonfuls of sugar you add to help the medicine go down; when you swallow queer writing, it still burns going down (if the writer has done it right). But as we say in the Southwest, spicy is an essential ingredient on the menu. What I have to say in my memoir will be considered controversial by some (many?), but this is the thrilling thing about queer writing, especially queer writing for an LDS audience, at this moment in history: You are saying ideas that have never been said before and thinking thoughts that have never been thought before. And that is exhilarating. It is also some serious Samuel the Lamanite wall testifying (cue the stones and arrows). You know what they say: today’s heretics are tomorrow’s saints. If you feel confronted by queerness as you read my memoir, I make this ask: Let us not separate from one another as we work together to address these issues. It is my deep and abiding hope that this book will spur reflection and action.

I began this post by introducing myself as one of the last members of the generation of Latter-day Saint young men officially taught to get married to a woman as a remedy to overcome “homosexual inclinations.” I am but one generation of gay men and one branch among the multiple, diverse boughs of the Latter-day Saint queer family tree representing each specific letter of 2SLGBTQIA+ Latter-day Saints. This sprawling generational genealogy has been created by the modern church’s ever-changing dominant narrative and policies about queer people. Today this towering queer family tree stands directly in the center of Zion. It is breathtaking in size and the amount of husbandry required within the generational branches to keep its roots of inequality and exclusion alive. It cannot be sustained.

I began this post by introducing myself as one of the last members of the generation of Latter-day Saint young men officially taught to get married to a woman as a remedy to overcome “homosexual inclinations.” I am but one generation of gay men and one branch among the multiple, diverse boughs of the Latter-day Saint queer family tree representing each specific letter of 2SLGBTQIA+ Latter-day Saints. This sprawling generational genealogy has been created by the modern church’s ever-changing dominant narrative and policies about queer people. Today this towering queer family tree stands directly in the center of Zion. It is breathtaking in size and the amount of husbandry required within the generational branches to keep its roots of inequality and exclusion alive. It cannot be sustained.

It cannot be sustained.