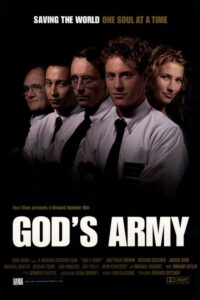

Twenty-five years ago today, on March 10, 2000, Richard Dutcher released the film God’s Army in Utah theaters. I’ve spent much of the two and a half decades since then writing a book and over sixty articles about all of the thousands of other Mormon movies that have preceded and followed it, going as far back as 1898. In fact, I suspect it became a bit of a personal mission of mine to debunk the common claim that God’s Army was the first Mormon film. Despite all of that, however, I would be hard pressed to name any motion picture that has been more influential to Mormon film and culture than God’s Army.

Other candidates exist. In 1913 the (lost) theatrical feature film One Hundred Years of Mormonism was one of the longest films ever made to that point, telling the story of the Church from Joseph Smith’s first vision to the founding of Salt Lake City. Not only was it the first film sponsored by the Church, it’s been called the most important Mormon film of the silent era because it was—and remains—the only film about pioneers that had actual pioneers in the cast and crew.

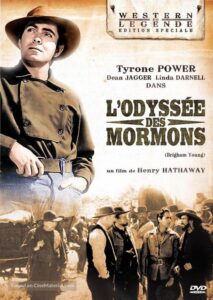

When Twentieth Century-Fox premiered their biopic Brigham Young in Salt Lake City on August 23, 1940, both Utah and the city declared it “Brigham Young Day.” Schools and businesses closed, 100,000 people flocked into the city to see the Fox stars’ motorcade, the First Presidency hosted the filmmakers in the Lion House, and the film premiered in seven theaters, a Hollywood record, an embrace between the Church and film industry showing just how much mainstream American society had come to accept Mormonism.

When Twentieth Century-Fox premiered their biopic Brigham Young in Salt Lake City on August 23, 1940, both Utah and the city declared it “Brigham Young Day.” Schools and businesses closed, 100,000 people flocked into the city to see the Fox stars’ motorcade, the First Presidency hosted the filmmakers in the Lion House, and the film premiered in seven theaters, a Hollywood record, an embrace between the Church and film industry showing just how much mainstream American society had come to accept Mormonism.

In order for Church leaders to permanently integrate filmmaking into the structure of the Church in 1953, they were first inspired by the twin films Church Welfare in Action and The Lord’s Way in 1948. Produced by “Judge” Wetzel Whitaker, the future head of the BYU Motion Picture Department, and many of his colleagues at Disney, these films became the first movies shown at general conference and laid the path for every Church-produced film since. Without them, Church filmmaking might not have become a permanent endeavor, or at least not as early as it did.

So yes, there were some remarkable achievements before God’s Army, but none of these, nor any other films, changed the landscape as drastically. I was a newly registered film student at BYU in early 2000 when rumors started spreading about someone who had made a movie about missionaries that was going to be released in commercial theaters. The audacity of such an idea was simply unbelievable, even among the very aspiring filmmakers who should have most envisioned such a film. When Dutcher himself came to show the trailer and speak at a Tuesday afternoon college forum (this was years before YouTube), the air in the theater was completely electric. More than one person was in tears, and every one of us felt how colossal a paradigm shift this was, a feeling that was replicated, for me, when I saw the film at the Provo Town Centre on March 11, a day after it came out. Mormon movies could now exist in the open, not just during seminary or Sunday school lessons, and they could move beyond devotional didacticism to portray realistic characters, with all their faults and triumphs. This is why, as I developed a model of the history of Mormon film, I called this Fifth Wave of Mormon film “Mainstream Realism”: God’s Army’s biggest achievement wasn’t just its theatrical release, but changing how Mormons were depicted on screen.

So yes, there were some remarkable achievements before God’s Army, but none of these, nor any other films, changed the landscape as drastically. I was a newly registered film student at BYU in early 2000 when rumors started spreading about someone who had made a movie about missionaries that was going to be released in commercial theaters. The audacity of such an idea was simply unbelievable, even among the very aspiring filmmakers who should have most envisioned such a film. When Dutcher himself came to show the trailer and speak at a Tuesday afternoon college forum (this was years before YouTube), the air in the theater was completely electric. More than one person was in tears, and every one of us felt how colossal a paradigm shift this was, a feeling that was replicated, for me, when I saw the film at the Provo Town Centre on March 11, a day after it came out. Mormon movies could now exist in the open, not just during seminary or Sunday school lessons, and they could move beyond devotional didacticism to portray realistic characters, with all their faults and triumphs. This is why, as I developed a model of the history of Mormon film, I called this Fifth Wave of Mormon film “Mainstream Realism”: God’s Army’s biggest achievement wasn’t just its theatrical release, but changing how Mormons were depicted on screen.

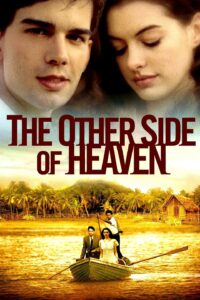

Well, the fire caught on at BYU and beyond. Mitch Davis was already working on The Other Side of Heaven, and soon Kurt Hale, Ryan Little, and others were working on Mormon films of their own. Before that April I myself, as a screenwriting major, gave Dutcher a dozen movie concepts, which he kindly accepted and wisely set aside. Feeling these ideas’ inadequacy, I went on to study the history of Mormon film, to see what else had come before, but my classmates like Christian Vuissa, Andrew Black, and others went on to found the LDS Film Festival and direct films of their own like Baptists at Our Barbecue, Pride and Prejudice, and the Mormon-tinged Napoleon Dynamite.

Well, the fire caught on at BYU and beyond. Mitch Davis was already working on The Other Side of Heaven, and soon Kurt Hale, Ryan Little, and others were working on Mormon films of their own. Before that April I myself, as a screenwriting major, gave Dutcher a dozen movie concepts, which he kindly accepted and wisely set aside. Feeling these ideas’ inadequacy, I went on to study the history of Mormon film, to see what else had come before, but my classmates like Christian Vuissa, Andrew Black, and others went on to found the LDS Film Festival and direct films of their own like Baptists at Our Barbecue, Pride and Prejudice, and the Mormon-tinged Napoleon Dynamite.

Casual observers of Mormon films can be forgiven for thinking there’s been a dozen or two movies that have come out in God’s Army’s wake—maybe they just remember the Halestone comedies like The Single’s Ward, or one particular title that they enjoyed, like Saints and Soldiers or Dutcher’s own States of Grace. But according to my records, when T.C. Christensen’s biopic Raising the Bar: The Alma Richards Story comes out this April, it will be at least the eightieth theatrical feature film made by and about Mormons since 2000, a respectable average of 3.2 films per year. There should probably be a few more, in fact, depending on how you count.

When God’s Army came out Dutcher frequently said that he wanted it to be the first of many, that he wanted a movement to follow him. And it did. It certainly had a messy beginning, with many, let’s say, “substandard” films and some high-profile feuding between Dutcher and Hale, and there have been fallow periods and, of course, many duds—you don’t reach eighty films without one or two clunkers. But the fact that even the worst of these Mormon feature films exists is a testament to the complete sea change that God’s Army ushered in.

When God’s Army came out Dutcher frequently said that he wanted it to be the first of many, that he wanted a movement to follow him. And it did. It certainly had a messy beginning, with many, let’s say, “substandard” films and some high-profile feuding between Dutcher and Hale, and there have been fallow periods and, of course, many duds—you don’t reach eighty films without one or two clunkers. But the fact that even the worst of these Mormon feature films exists is a testament to the complete sea change that God’s Army ushered in.

New genres emerged. Historical films like Handcart, The Work and the Glory, 17 Miracles, and Redemption: For Robbing the Dead continued the tradition of Church-produced films like Legacy and The Mountain of the Lord, but often with a different tone than would be found there—the Church hardly would have sanctioned a film about grave robbing, for instance. Early Halestone comedies, which had their share of great humor, led the way for more nuanced and subtle comedy, from the early The Best Two Years to the magnificent Once I Was a Beehive, one of the best films in the canon. Thrillers—see Dutcher’s Brigham City and Garrett Batty’s The Saratov Approach and Freetown—took Mormon film in new directions, and we’re now seeing horror added to the mix with Heretic—a film largely made by non-Mormons—and Barrett and Jess Burgin’s The Angel, now in preproduction. I would argue that the canon has even expanded to allow for what I would call “post-Mormon cinema,” films that aren’t antagonistic but which do explore a loss of faith or heterodox relationship with the Church, and which therefore reach insights unavailable to those who have never questioned the faith. Hawaiian Punch, Dutcher’s Falling, and Rebecca Thomas’s magical realist Electrick Children—which I saw at the IFC Center in Greenwich Village, if that indicates Mormon cinema’s reach—show in real human terms what it’s like when the Mormon experience falls short.

And speaking of Thomas, it took far too long, but women gradually emerged as screenwriters, directors, and protagonists in Mormon films. While this almost never happened before God’s Army—the Church films Shannon and Legacy, or others about the Relief Society or Primary, are some of the only I can quickly think of—the mainstream realism that God’s Army brought in also gave license to female filmmakers to tell their stories. From Heidi Johnson, who co-wrote the first “sister missionary film” The Errand of Angels, to Carol Lynn Pearson, Melissa Leilani Larson, Chantelle Squires, Kathryn Lee Moss, Brittany Wiscombe, and Margaret Blair Young, many women have created or helmed fictional features. I’m pleased to say that there have now been more films about Emma Smith than Joseph.

As Young’s work in Africa shows, Mormon films have also spread far beyond the Mormon corridor and the insularity that critics complained about with The Singles Ward and The RM: The Other Side of Heaven and its 2019 sequel were shot largely in Polynesia and Australia; The Best Two Years and The Errand of Angels shot scenes in Europe; Piccadilly Cowboy was filmed entirely in England, Melted Hearts: El Otro Lado del Corazon and A Promise of the Heart: Hablando de Suenos in Mexico, Freetown in Ghana, and Heart of Africa and its sequel in the Democratic Republic of Congo, reportedly the first film ever created there by native Congolese filmmakers. As noted, The Other Side of Heaven was begun before God’s Army’s release, but who knows if all these international features would have been completed without the robust market Richard Dutcher created.

Finally, speaking of the market, it wasn’t just more features that followed Dutcher’s film: the burgeoning market of home DVD sales in the early 2000s (and the aforementioned LDS Film Festival) invigorated an entirely different area of Mormon cinema, allowing financial viability for short films, documentaries, and straight-to-video title, giving us the work of exceptional filmmakers like John Lyde, whose films didn’t have the financial backing for a theatrical release but which often outshown some films that did. Over the past fifteen years we’ve also seen the richest period ever for Mormon documentaries, something that might not have happened without all this groundwork since 2000. Today the movement has lasted into the age of the internet and streaming video, putting us in a different, sixth, wave of Mormon films, but one which will retain the mainstream realism of the Fifth Wave regardless of the distribution platform and even the filmmakers’ faith. We’re seeing this depth and dynamism in Heretic, Under the Banner of Heaven, The Order, as well as a continual stream of nonfiction films.

I haven’t written about the film itself—I suppose that would be a whole other essay—but God’s Army is a very good film. It’s well written, well shot, well acted, and well edited. It’s a tense, funny, and emotional achievement. But for my money, though it ranks high, it is not one of the very best Mormon films; it’s not even Richard Dutcher’s best film—or second best! But it was absolutely revolutionary twenty-five years ago in a way that young audiences and filmmakers today might not realize. I keep recalling the energy, tears, and emotions in that theater in the basement of the now-demolished HFAC building at BYU, when it dawned on all of us there that Mormon film, and in a way Mormon culture, could now stand unapologetically on its own; that revelation is a moment that will never return, because God’s Army was successful in fulfilling Dutcher’s vision of creating a Mormon cinematic movement. Mormon film in all its iterations is now mainstream, and no other motion picture did more for that than God’s Army.

Randy Astle is the author of Mormon Cinema: Origins to 1952 and over sixty articles on Mormon film. He has taught Mormon cinema at Brigham Young University, acquired hundreds of DVDs as the BYU library’s Mormon Film Specialist, edited special issues of BYU Studies and Mormon Artist magazine, served two years as film editor for the AML’s journal Irreantum, programmed film screenings at the Sunstone Summer Symposium, and created the annual academic forum at the LDS Film Festival. He received the Mormon History Association and B. H. Roberts Foundation Research Grant in 2023 and an award for criticism from the AML in 2008 and 2019. He is currently writing a second book, Mormon Cinema: 1953 to 2024.

Randy Astle is the author of Mormon Cinema: Origins to 1952 and over sixty articles on Mormon film. He has taught Mormon cinema at Brigham Young University, acquired hundreds of DVDs as the BYU library’s Mormon Film Specialist, edited special issues of BYU Studies and Mormon Artist magazine, served two years as film editor for the AML’s journal Irreantum, programmed film screenings at the Sunstone Summer Symposium, and created the annual academic forum at the LDS Film Festival. He received the Mormon History Association and B. H. Roberts Foundation Research Grant in 2023 and an award for criticism from the AML in 2008 and 2019. He is currently writing a second book, Mormon Cinema: 1953 to 2024.