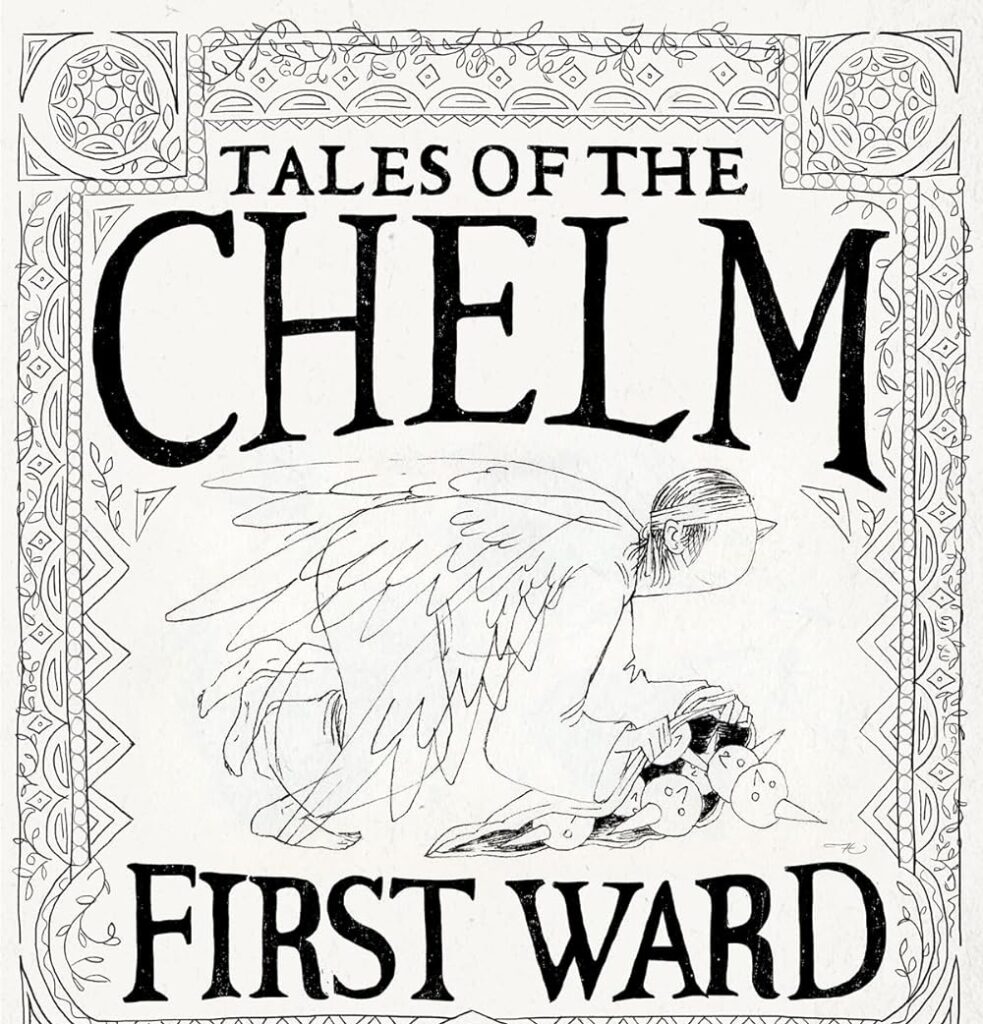

Title: Tales of the Chelm First Ward

Authors: James Goldberg, Nicole Wilkes Goldberg, Mattathias Singh

Publisher: BCC Press

Genre: Fiction

Year Published: 2024

Number of Pages:

Binding: Paper

ISBN: 978-1961471030

Price: 13.95

Reviewed by Dai Newman for the Association of Mormon Letters

Chelm, in the traditional Jewish stories, is a town populated by Amelia Bedelia’s, Bertie Wooster’s, the butt of blonde jokes, and the worst people from your college classes who would derail discussions with useless hypotheticals. These well-meaning fools come at problems in all the wrong ways and their solutions are sincere but more often than not outrageously unsound. The Goldbergs imagine what would happen if some of these simpletons joined the Church and tried their very best. The resulting 32 stories in Tales of the Chelm First Ward are very funny but also surprisingly perceptive parables.

Narrowing down the best stories in the book would tax even Zalman the Learned and Menachem Menasche, Chelm’s resident scholars, but a taste should whet most appetites for the whole collection. Fruma Selig frets because her daughter is not “marrying in the church” but in the temple instead. The ward council struggles with its mission plan because, unlike other European wards, they have grown quickly, and “we learn most from our failures” so “every single ward in Europe knew more about missionary work”. Clever Gretele, when the ward announces a temple trip, decides the way to get her non-Mormon mother to accept the gospel after she dies is “by setting up some peer pressure in advance” and preparing her mother’s pushy aunts for posthumous ordinances. Beynish loses his job but pays his tithing for the first time in years but it’s lard equal to one-tenth of his “increase” (the weight he’s gained from stress eating). The bishop is stumped about a calling for Oskar the Miser (“Any calling involving compassionate service was obviously out”) but Osakr’s stingy innovations as ward librarian have a certain beauty to them. A man, already distressed that his parents have become Mormons (“As if that were an ordinary European religion and not a second-tier background menace from old novels about the Wild West”), agrees to let his daughter go to girl’s camp because his wife convinces him that “the best cure for her interest in Mormonism is simply more Mormonism”.

The Saints in Chelm retain a lot of their Jewish traditions but have expanded them to include their new faith. The ward hosts annual Purim spiels, though the elder’s quorum president grumbles about being cast as Haman again, and Passover seders with a Haggadah that sweeps up early Church history and the Book of Mormon into a strange olio. A deacon seeks relief from fast offering collection by searching the Talmud for the maximum number of steps allowed on the Sabbath. The misperception that Joseph Smith started the “great repair” sparks connections to tikkun olam (“it only made sense that religion was just as broken as the next thing”). Knowing Jewish customs will help readers, but the audience for this seems squarely to be Latter-day Saints who have struggled to sit through ward councils (in Chelm they are “exactly as efficient as every other ward council anywhere), suffered tense Gospel Doctrine classes (“you could bear testimony of it before the ward on Fast Sunday: you knew, with every fiber of your being, that Brother Cohen was going to have a concern”, or tried corralling Primary children (“It was entirely possible that no one knew. But it was Primary: half of them raised their hands anyway”). The Goldbergs do include a glossary of some terms, though even these are an opportunity for delightful humor more than strict education.

Like the best satire, these stories are deeply funny without being mean. More impressively, they have genuinely tender lessons. Gretele longs to teach primary children a better way of being righteous “besides her own system of having to try very hard all the time and then screw up all the time anyway”. When Stefan, who married into Chelm, asks Zelda why she spends all meetings in the foyer, her explanation quietly praises the comforts of the community. Tzipa’s efforts to live the Family Proclamation perfectly hoping to bind God to bless her with a long-wished for child handles the thorny issues of infertility and patriarchy delicately. The truth a skeptical teen uncovers about what elderly Henya is doing when other ward members think she is speaking with God is surprisingly moving. These stories, even with their outlandish humor, manage to be faith-affirming in ways that avoid schmalz in no small part because they do not try to airbrush over the missteps, difficult personalities, and frustrations of the characters. In a very different, and better world, these stories would be shared as powerful parables in sacrament meetings and lessons.

In combining both Jewish and Mormon beliefs and practices, the Goldbergs weave a complex portrait of a small town and its idiosyncratic ward. Most readers with a connection to contemporary LDS life, regardless of how positive or negatively they feel about it, will be enthralled by these stories. They interrogate culture and policies to highlight absurdities. Nuanced spiritual lessons come from unexpected places. Conversions bring small, subtle shifts as well as loads of new complications. And all of this comes with a wide-open heart and loads of laughs. Tales of the Chelm First Ward is a stellar book that readers won’t regret exploring.