Review

=======

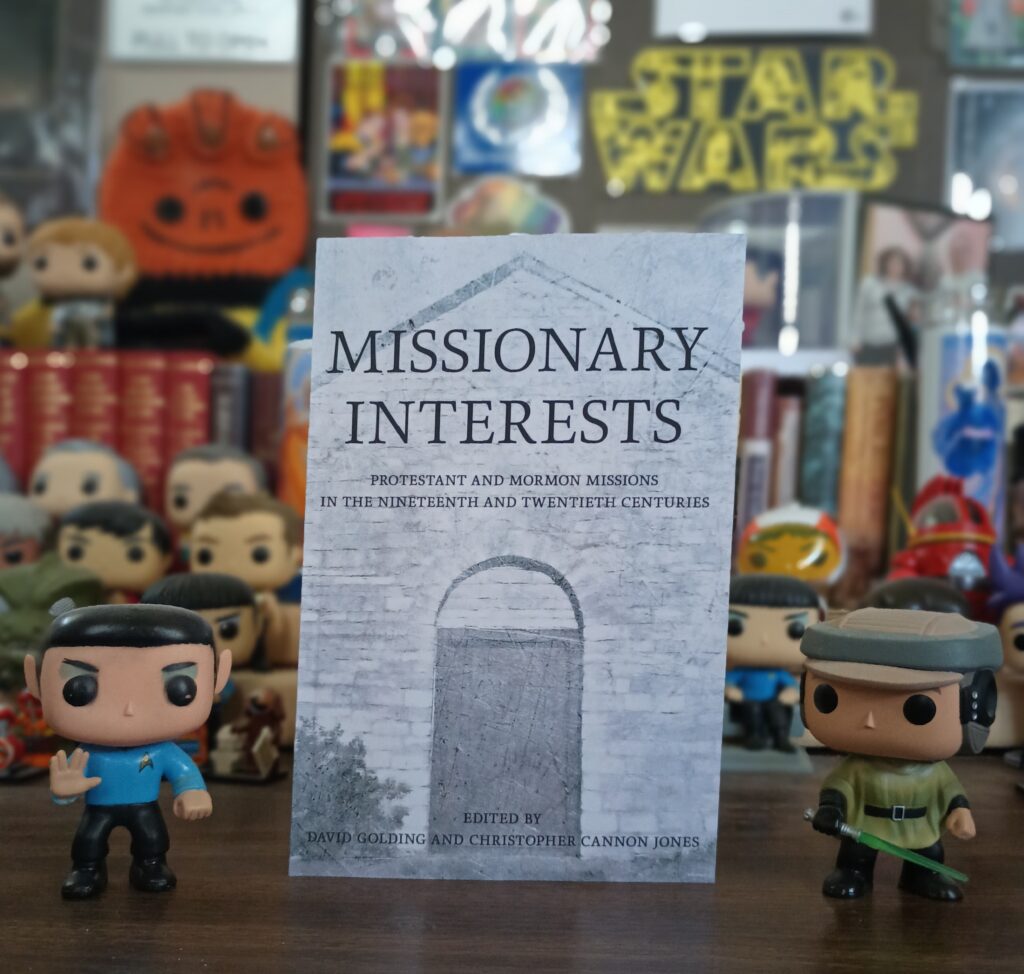

Title: Missionary Interests: Protestant and Mormon Missions of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries

Editors: David Golding and Christopher Golding Jones

Publisher: Cornell University Press (April 15, 2024)

Genre: Non-fiction

Year published: April 15, 2024

Number of pages: 228

Binding: Hardback

ISBN-10: 1501774425

ISBN-13: 978-1501774423

Price: $130.00

Reviewed by Melvin C. Johnson for the Association for Mormon Letters

David Golding and Christopher Cannon Jones have cooperated to gather a collection of first-rate essays that explore an assemblage of uniquely lived proselytizing experiences in Missionary Interests: Protestant and Mormon Missions of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Their reasons, tests, and trials examine as well as reveal the effects of their efforts to evangelize the globe’s different communities. I agree with Benjamin Park, author of American Zion and the Kingdom of Nauvoo, that this book “is an exciting contribution to [the missionary studies of and on]…Mormonism and Protestantism.”[1]

This volume appeals to me; it is filled with perceptive and interesting chapters on Protestant and Mormon missions across time and space, which deserve to be enthusiastically read and examined by scholars and students. Laurie F. Maffly-Kipp, at the beginning of the forward, so aptly notes that “Who cannot be fascinated by missionaries, those souls willing to renounce everything they have known in life for the sake of an ideal” (vii). Missionaries from Protestantism and Mormonism jointly shared a common goal, to convert all the world to know Christ’s name and bring all mankind to salvation. The missionaries tried to cross the space between the evangelizer and the evangelized, treading the differences of race, sex, culture, language, norms, and expectations.

Kathryn Gin Lum’s chapter, “Heathen: Religion and Race in American History” ambitiously places the concept of “heathen” at the center of America’s religious history. In a solid historical narrative, Gin Lum tracks the evolution of the term “heathen” from antiquity into the nineteenth century. Originally the process looked at Europeans resisting Christianity (think Teutonic knights and non-Christian Slavs in the Baltic regions). The term developed as European Christians expanded into new lands and other non-Christian peoples. A key result was the shaping of Americans perceiving non-Christian realms as being ‘broken’ heathens in need of Christian redemption. The writer’s personal lived-in experiences informed by meticulous research reveal an intersection of race and religion opening insights into how American culture can be self-perceived as special through its deployment of humanitarian resources.

Emily Conroy-Krutz investigates in her book chapter “Before ‘Woman’s Work for Woman’: Protestant Missionary Applications and Gender,” the conflicting and constrained role of women in early American Protestant missionary societies. She explores the complexities of the roles of fluctuating gender dynamics in missionary organizations, emphasizing how women’s employment was both crucial but often hampered by male-dominated expectations and limitations based on women’s sex. An example by Conroy-Krutz focuses on the conflict of a woman’s active commitment to fundraising contrasted with limited power in policymaking on how to use monies.

Her facility in handling and extracting material from contemporary sources and documents reveals the hurdles and expectations countered by women in this religious calling as while their attempts to pilot their pathways through social expectations. Conroy-Krutz’s delivers worthy conclusions into the crossing of, and at times, confusing pathways of religious belief on the pathways of mission work during an important time in American history.

Devrim Ümit McDermott, a transnational historian specializing in American Protestant missionaries laboring in the field during the late Ottoman period, peers into their intricate dynamics of interactions in and with the Ottoman State. In her work titled “Humanitarian Encounter between the Ottoman State and the American Protestant Missionaries in the Late Ottoman Era,” Ümit explains how these missionaries navigated the complex geopolitical landscape. By studying their interactions, she reports the impact of their efforts on both religious and political fronts. The interaction of humanitarian endeavors explains valuable insights into the interplay between humanitarian aid efforts and their effects on broader historical contexts.

Taunalyn Ford Rutherford’s research investigates the impact of Scottish perspectives on the behavior of Mormon missionaries and the outcomes of their efforts. In her essay titled ‘Dueling Orientalism: The Scottish Imagination in the Mormon Mission Mind,’ she explores how Scottish views influenced missionary behavior, particularly within the context of the ‘new’ America. By shedding light on cultural differences and adaptive approaches, Rutherford’s work highlights the complexities of cross-cultural interactions and the intersection of religious identity with ingrained cultural habits. Her insights contextually incorporate an understanding of the evolving dynamics of missionary work and its effects on diverse communities.

Amanda Hendrix-Komoto informs those of us working with the Mormon and Protestant evangelical messengers on their ministering to the indigenous peoples in Western America. “Shoshone Worlds, Bannock Zions” looks at their interaction in the then ephemeral border of what is now Utah-Idaho. What did they do to understand and cope with the complex differences of culture, race, and belief structures? She notes that President David O. McKay, fifty years after serving as the presiding elder over the missionaries called to Scotland, in the 1950s created “… a modernization of mission work” [through standardizing] mission government processes, policies, and curricula into a centrally defined and replica program.” (149)

The article by Jeffrey G. Cannon, “Traveling Elders: The Latter-day Saint Gaze on Africa in the Early Twentieth Century,” explores the “Mormon perspective” and positions “the Latter-day Saint gaze on Africa within the broader Anglo-American Christian imagination” (66). Their viewpoints were not monolithic but varying in nature. That changed their tactics on proselytizing and targeting potential converts. Mormon missionaries recognized Black Africans as the exotic Other but did not interact with them at the beginning of the twentieth century. They focused on the white settlers rather than the native Africans until the Church could not ignore them and other peoples of color. [2]

Natural Disasters and Humanitarian Aid,” by Lauren F. Turek explores how responses to natural disasters were developed, crafted, and conducted by evangelical missionaries. The reader will be startled to find that practical responses often outweighed spiritual and romantic assumptions. Turek’s work is a compelling exploration of the role of humanitarian aid and masterfully illustrates how practical solutions often supersede spiritual or romantic notions in these scenarios. The chapter provides an insightful look into the development and execution of aid strategies, challenging the reader’s preconceptions about the motivations and actions of these religious groups. It is an obvious revelation contextually that pragmatic responses take precedence in dire situations, painting a nuanced picture of missionary work. For those interested in humanitarian aid and its complex interplay with faith, this is a necessary study.

David A. Hollinger’s essay “American Missionaries and the Struggle for Control of Christianity’s Symbolic Capital” examines the intricate dynamics surrounding authority and representation within Christianity. The symbolic capital of individuals and populations varies. The Church of Jesus of Latter-day Saints (LDS) and Roman Catholic Church permitted in the Great Basin and the northern Atlantic West church community’s transacted more traditional organizational control. Hollinger explores how the churches and their memberships navigated the complexities of symbolic capital.[3] Some Protestant groups empower rank-and-file members worldwide, while others keep traditional control. For instance, American Methodists advocating for same-sex marriage face opposition from African and Latin American delegates. Compare the Seventh-day Adventists to ordain women in the United States as biblical literalists in the southern hemispheres cite Paul to suppress women in churches. Note that some Baptist churches have embraced gender opportunity for women to serve in leadership roles, others align with more traditional views that restrict women from teaching in certain contexts. Hollinger’s work offers valuable insights into the ongoing struggle for authority and representation within Christian groups.

David J. Howlett’s chapter “Inventing Rupture in India and America: Adivasi Converts, Hindu Nationalists, and American RLDS Missionaries, 1966-1996” delivers an interesting view of the crossroads of different religious groups at that time. Focusing on Adivasi converts, Hindu nationalists, and American RLDS (Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints) missionaries, Howlett investigates their religious transformation. By bridging continents and cultures, he uncovers the complexities of conversion, identity, and the clash of worldviews. Howlett’s work on globalization, religion, and local legacies reveals new panoramas of local religious communities in America and India.

Melissa Wei-Tsing Inouye’s “Technological Christianity: Transferring Processes, Forms, and Organizational Tools within Global Missionary Encounters” investigates the crossing of missionary work and technology as she researches how methodologies, procedures, and informational and organizational tools were impacted global missionary encounters. By examining the practical aspects of missionary efforts, Inouye sheds light on the ways technology influenced evangelization and communication within religious communities. Her work reveals the dynamic relations between faith, technology, and cross-cultural engagements in international global efforts.

David Golding, in his chapter titled “Missing Missiology: Latter-day Saint Missionary Pragmatism and the Search for Scholarship,” takes apart the practical approaches to evangelization by Latter-day Saint missionaries. He demonstrates how practical considerations are interconnected with scholarly pursuits within missionary circles. By examining the tension between pragmatism and academic rigor, Golding invites vital consideration of the processes, intents, and effectiveness of missionary work. The interplay of the faith-based mission and rational investigation demands thoughtful engagement and self-awareness in religious outreach. An example of dealing with the missionary aware of himself/herself as ‘the Other’ in a different culture would be a primary goal of the missionary.

In summary, we can see the impact this work will have on the reader. As Laurie F. Maffley-Kipp writes,

As with all experiments, the scientists of Christian missions confronted frequent failure, missed and novel opportunities, and unanticipated consequences: the Shoshone who used Mormon temple construction to honor their massacred relatives; the young German who relied on Latter-day Saint technologies to resist the Nazis; the natural disasters that open new doors for evangelical outreach; and the social ruptures that lead, ironically, to fundamental changes in the cultures of the missionaries themselves. So, too, missions have brought out less than noble sentiments, as evangelicals have had to discover who is “deserving” of their calling or their message. Why white and not Black South Africans? Why men and not women? Why Ottoman Christians, not Muslims—and only those who were not Catholic? (ix).

Missionary Interest tears asunder simplistic representations about missions and conversion. By juxtaposing Mormon and Protestant missionary efforts, the editors and writers offer a nuanced exploration of faith, culture, and human interaction. This book offers valuable insights into the history of religion, cross-cultural encounters between missionaries and the Other, or the complexities and unique difficulties of mission work. Whether scholar, layperson or simply a curious passerby about the past, this collection invites the reader to look at the world of Mormon and Protestant missionary passion and its impact on societies worldwide.

[1] https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/9781501774447/html

[2] Matthew L. Harris, Second-Class Saints: Black Mormons and the Struggle for Racial Equality (New York: Oxford University Press, 2024), 44. Harris, in his forthcoming corpus, examines in detail the impact of the Otherness of potential black converts in the African missions prior to and after 1978. One example was President David O. McKay first considered Philippine Negritos as cursed and withheld priesthood ordinations, he then “reversed himself and said they could be ordained to the priesthood.” In other areas of the world, McKay ordered the mission presidents to not teach people of color and to concentrate on whites.

[3] “Symbolic capital” ~ “Bourdieu’s concept of symbolic capital plays a crucial role in understanding the dynamics of power, social hierarchies, and cultural production. Symbolic capital refers to the resources and advantages that individuals or groups possess, which are based on their social position, reputation, and cultural capital” easy sociology. com/general-sociology/understanding-pierre-bourdieus-symbolic-capital-in-sociology.