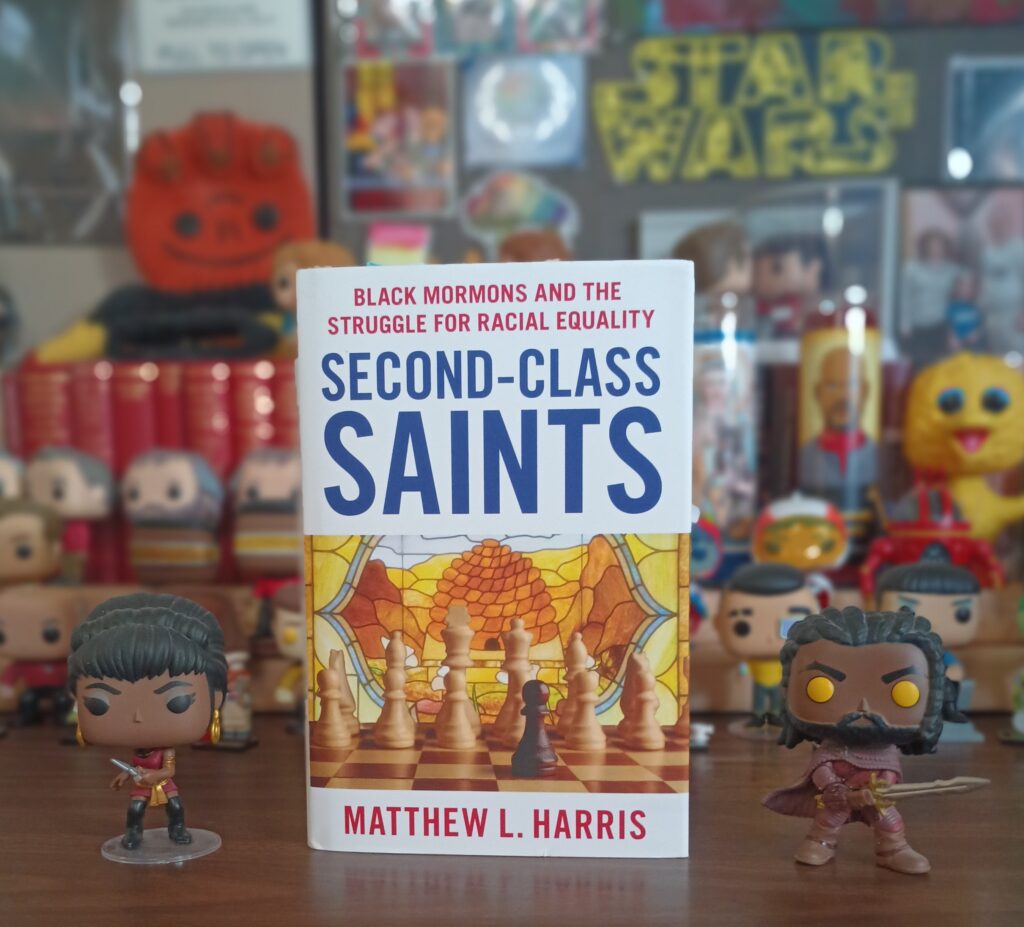

Title: Second-Class Saints: Black Mormons and the Struggle for Racial Equality

Author: Matthew L. Harris

Publisher: Oxford University Press

Genre: Religious Non-fiction, Academic

Year Published: 2024

Number of Pages: 460

Format: Hardcover

ISBN: 978-0-19-769571-5

Price: $39.99

Reviewed by Conor Hilton for the Association of Mormon Letters

Matthew L. Harris’ Second-Class Saints: Black Mormons and the Struggle for Racial Equality is a stunning, monumental book. The culmination of fifteen years of research, Second-Class Saints offers a thorough recontextualization of the lifting of the priesthood and temple restrictions in 1978, with an exploration of some of the aftermath up through the present day. The book immediately joined my shortlist of the most important books for folks wanting to understand the realities of the institutional church better, whether that’s in order to renegotiate their relationship to that institution and religion or simply in pursuit of further light and knowledge.

Second-Class Saints is grounded in archival work and a wide range of sources, many of which have not been available to researchers before now. Harris uses these sources to weave together a riveting—at times frustrating, enraging, and occasionally even hopeful—story for how the priesthood and temple restrictions were lifted. The book is packed with quotes and insights from these sources that enrich the overall argument and make the book a treasure trove of tantalizing details and anecdotes that inspire their own further study and research.

Harris focuses on the 50-year period before 1978, demonstrating the different personalities, approaches, and discussions that took place over those decades, revealing the ways that outside factors shaped and informed how those conversations went. Throughout his telling, Harris is honest, bracing, and fair. He periodically goes out of his way to recognize the efforts that individuals and the institution have made to lessen and address the harm of the ban, to root out racism, and other laudable actions while not avoiding the countless actions and statements that present the persistence and presence of racist attitudes and actions (whether those were conscious, unconscious, or something in-between, Harris largely leaves up to the reader).

One specific example of the new view on this history that Harris offers surrounds Spencer W. Kimball praying in the temple for hours, more or less daily, in early 1978. Growing up in the church, I largely heard this anecdote invoked as a sign of the amount of dedication and effort that Pres. Kimball had before revelation came to lift the ban. Yet, in Harris’ telling, Kimball had decided sometime in 1975 or so that the ban needed to be lifted. The prayers and hours in the temple then were about Kimball seeking divine guidance and support, but not for what needed to happen with the priesthood and temple restrictions. Instead, the purpose, in my reading of Harris’ narrative, was to gain inspiration for how to persuade the other members of the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve to embrace the conviction that Kimball had that the ban needed to be lifted. This strikes me as an equally if not more, important lesson to learn. Sometimes, the harder inspiration or revelation to obtain is how to make something happen, not what needs to happen.

Harris’s book is undoubtedly important to the study of race in the church, as well as the study of institutional change and institutional operations. Yet, perhaps the most significant contribution Second-Class Saints has to offer is a challenge to narratives of prophetic authority and revelation, particularly at upper levels of the church hierarchy. Some readers may bristle at the ways that Harris charts out the influences of scholars, activists, faithful members’ stories and questions, protests, public opinion, and all sorts of other people and factors on the decision. However, Harris is committed to the archival record, working to not speak beyond what the sources offer. In my reading, these influences do not negate the possibility of revelation or divine inspiration but instead demonstrate the complexity of seeking God’s will and the number of social and personal factors that may prevent us from seeking and receiving it. This much richer and more complex understanding of revelation should spark a change in how we collectively imagine the role of prophets and how we are called to interact with them.

Second-Class Saints: Black Mormons and the Struggle for Racial Equality is a must-read. I will be pondering and grappling with the implications of Harris’ work for years to come and can only hope that other scholars will do the same, extending, challenging, and complicating the phenomenal work that Harris does here. My own grappling so far has taken the form of two or three long-time germinating essay ideas that need to be at least partially reimagined in the wake of Second-Class Saints. I hope all can read Harris’s clear-eyed accounting of how the priesthood and temple ban was lifted and may we all do more to root out racism in ourselves and in this beloved Mormon community.