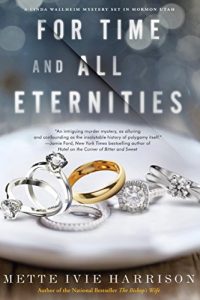

Title: For Time and All Eternities

Author: Mette Ivie Harrison

Publisher: Soho Crime (Soho Press, New York)

Genre: Crime novel

Year of Publication: 2017

Number of Pages: 326 (in pre-publication version)

Binding: paper

ISBN13: 978161695-666-0

Price: $26.95

Reviewed by Julie J. Nichols for the Association for Mormon Letters

In Jane Smiley’s Thirteen Ways of Looking at the Novel (Anchor Books 2005), she says:

“All novels exist discretely as items in the catalog of novels….We can’t really understand any one novel without comparing it to others—not necessarily to decide whether it is great, greater, or greatest, but just to see how in any particular novel all the potential ingredients are chosen and assembled. In addition, all novels happen to be related to many other forms of discourse….” (Smiley 179)

Smiley then conceptualizes, for our ease of understanding, a clock face with twelve types of discourse, which, she theorizes, have varying weights in any one novel. The twelve types are travel; history; biography; tale; joke; gossip; diary/letter; confession; polemic; essay; epic; and romance. Her argument is that the lengthy written prose narrative-with-a-protagonist which constitutes a novel (Smiley 14) cannot avoid incorporating, utilizing, almost sometimes entirely appropriating one (and sometimes more) of these types of discourse as its principal driving force. She makes a good case. In Thirteen Ways she describes her post-9/11 bibliotherapy as reading one hundred novels, and seeing these interwoven kinds of discourse as one of the wise and witty ways she came to understand the form.

What does any of this have to do with the third novel in Mette Ivie Harrison’s “Bishop’s Wife” series?

Quite a lot. Recently I reviewed the first two in the series, where I noted that “For those of us who resolve contradictions between Mormon efforts at perfection and the realities of life differently than Linda, her bishop husband, and the people in their ward, the ‘[anthropologically neutral]’ point of view in The Bishop’s Wife can render Mormonism troubling.” I suggested that though Harrison’s novels are a good read, deserving of publication by a national press and deserving of a nomination for a 2015 AML award, they “should raise important and necessary questions about Mormonism itself in every thinking Mormon’s mind” because they render the majority of their Mormon characters as naively rigid, in some ways downright stupid, incapable of independent thought and critical judgment. These are not qualities I like to see my people characterized by. It doesn’t please me as a reader to see the novel used as a platform from which to show the low points of my tribe’s potential.

And For Time and All Eternities, in my opinion, is even worse. It’s not so much that the mainstream Mormons come out looking thoughtless and superficial (though some of them do). It’s that the major discourse type Harrison has chosen to drive her novel is polemic.

This discourse type, according to Smiley, “uses emotion [in this case a story about women in an abusive polygamous household]…as argument, using events, characters, and insights in service to a rhetorical point. The pleasure, for the reader, is eloquence intensified by feeling, and the sense that the writer is pushing the bounds of propriety” (Smiley 180).

A dictionary.com definition of “polemic” is “a controversial argument…as one against some opinion, doctrine, etc.” The bottom line: For Time and All Eternities is thinly disguised polemic against two things: the Church’s recent policy change regarding same-sex marriage, and polygamy. And mainstream Mormons don’t come out so well for having anything to do with either.

Actually, in the case of the former, the polemic is not even thinly disguised. Harrison’s author’s note at the end of the novel describes how she began drafting the novel before the “Exclusion Policy” (as she calls it) was leaked, and how afterward, she knew she couldn’t not write against it. She says that in the first two books, the protagonist Linda Wallheim (misspelled in the earlier review) wasn’t a stand-in for herself, but “perhaps she is more like me in this book than she has been in any other” in her fierce rejection of the anti-gay policy and her clinging to “new friends in progressive Mormonism” (320).

Harrison also describes her research process in regard to polygamy. Her bibliography is five pages long. She interviewed many members of various polygamous factions. Her conclusions are strong: “The neglect of children, the abuse of women, the lack of education—these are all real problems, not to mention the emotional scars that come from a controlling community” (318).

My objection to all of this is not that she’s against the new policy (I am too) or that she finds polygamy reprehensible (I do too, though I have interacted with a member of the family who made TLC’s “My Five Wives” and she seemed reasonable and sympathetic enough). The problem is that the novel is a platform for these ideologies. If that doesn’t bother you, by all means read it! But everything—plot, characters, and commentary by the first-person protagonist—all are in the service of resisting and rejecting this fallout from Mormonism’s worst sides.

The plot and characters: Linda Wallheim, wife of a Mormon bishop (Kurt), is concerned when her son Kenneth takes her aside to tell her that he’s become engaged to the daughter of the polygamous patriarch Stephen Carter (sorry, Sunstone! Harrison really named him this!)

Linda has known for a while that Kenneth is falling away from the Church, but she knows marriage into a polygamous community will be especially complicated. When the fiancée (Naomi), whom Linda likes almost against her will, confesses that she’s worried about her little sister Talitha, Linda feels compelled to help. She and Kurt go out to the compound to meet the family and find a great many complex problems stewing among the wives (Rebecca, Jennifer, Sarah, Joanna, and Carolyn) and neighbors. The bishop leaves the place fairly quickly, unable to stomach the weird vibes, but when a member of the family is found murdered and the family moves rapidly to cover it up, Linda refuses to leave until she’s done all she can to bring the perpetrator to justice.

It’s tempting to say who dies, because of course that’s central to what happens afterward. But it’s a spoiler. Suffice it to say, perhaps, that Linda’s insistence on staying at the compound, putting herself and her son and his fiancée in danger, is a bit much. And the pages and pages of explanation before the murder are also a bit hard to digest, all of Harrison’s polygamy research expressed in long expository dialogues between Linda-and-Kurt and Rebecca-and-Stephen.

There’s no denying that Harrison’s facility with setting and character development help carry the novel. Readers will want to see what happens, and will be frustrated (as I’m sure Harrison wants them to be—that’s one of the functions of polemic, remember?) with the blatant abuse and anger in the family. Clues come almost too fast and too coincidentally, though, and Linda’s vacillations between progressive righteous indignation and Mormon-mother tender sympathy, all within two days of meeting the fiancée and the family, do push against the bounds of—well, if not propriety then credibility, perhaps.

The first lesson Harrison seems to want us to glean from this novel is that polygamy is inherently bad for anyone, because, as D&C 121 says so well (though Harrison never quotes any scripture), “it is the nature and disposition of all men, as soon as they get a little authority…they will immediately begin to exercise unrighteous dominion.” The second is that the Church is fallen—because of polygamy and because of unrighteous policies. The third is that though there are well-meaning members like Kurt Wallheim, adherence to rules and regulations undercuts their thought processes.

As her author’s note makes clear, Harrison is herself in a painful process of pulling away. This novel makes that obvious. If you don’t mind polemic, it’s a provocative piece of work.