Review

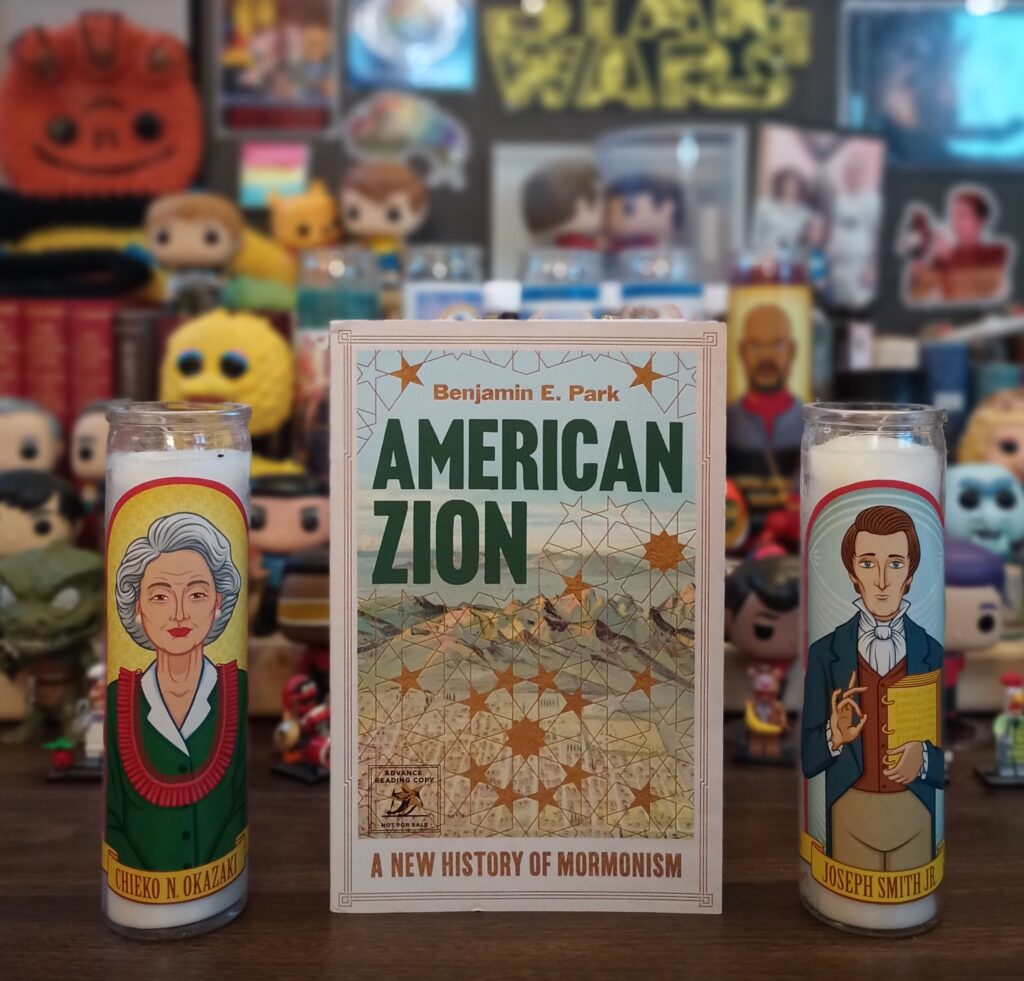

Title: American Zion: A New History of Mormonism

Author: Benjamin E. ParkPublisher: LiverlightGenre: Religious non-fictionYear Published: 2024Number of Pages: 478

Format: PaperbackISBN: 9781631498657

Price: $35

Reviewed by Conor Hilton for the Association of Mormon Letters

Ben Park’s American Zion: A New History of Mormonism is a monumental achievement. Park weaves together a remarkable amount of American political and religious context with Mormon histories, creating a deeply researched, readable narrative of the many Mormonism’s that have been present since the Church’s founding and persist in various ways to today.

Reading American Zion had me cheering, fist raised in celebration, and then bowing my head in shame and frustration, both proud of and disappointed in my people’s past. The book is truly impressive in terms of scope, presenting ten chapters, along with a prologue and epilogue, each chapter covering roughly 20 years or so, taking readers from 1775 to the present. The dating of the book demonstrates the ways that Park leverages his training as a historian of American political and religious culture to delve into the ways that the United States’ history is intertwined with the history of Mormonism. The increasingly global nature of the church may lead future historians to identify different meaningful contexts to place Mormonism in, but for now, Park’s choice leads to rich and informative results.

Park packed the book from start to finish with interesting anecdotes and historical tidbits, drawing on a vast array of sources and historical research. Many of the individual narratives were familiar to me in some form, but there were still countless surprises seeing the way that Park put the entire narrative together. I was often caught off guard by the relationship between different events or people that for whatever reason I had categorized as separate in my mind, but Park draws together to shape his narrative of the many Mormonisms and the institutional church’s arc towards assimilation (and repeated wrestling’s with the implications of that arc, including movement away from).

Throughout the book, Park includes brief discussions of Mormon literature. I was very pleasantly surprised to see this brought into the narrative and incorporated into the overall history of Mormonism. I hope that Park’s small interventions in this area can lead to more literary critics and historians diving into Park’s history and claims to identify ways the literature agrees with, challenges, and complicates it.

In a brief comment following debates between Sterling McMurrin and Hugh Nibley, Park notes, “That the two figures [Nibley and McMurrin] existed on the same spectrum of LDS thought–the same spectrum that also included Bruce R. McConkie and Juanita Brooks–demonstrated the schisms within the Mormon intellectual tradition” (271). Here, and throughout the book, Park carefully and deliberately traces multiple threads within Mormonism, including periodic discussion of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, now the Community of Christ. I am thrilled by this expansive and nuanced approach! Park’s work highlights the contested nature of Mormonism, drawing attention to the range of engagement with it and various interpretations that are offered at any given time, let alone the wider diversity of interpretations made available by seeing the historical shifts and evolutions.

One thread that Park returns to repeatedly is the place of gender and thinking about it. Perhaps the most interesting and new to me tidbit in all of that discussion is this, “[Sarah] Kimball declared that traditional gender spheres did not supply space ‘sufficiently extensive’ for women to exercise their ‘God-given powers and faculties’” (124). Where the Church as I have experienced it, largely doubles down on traditional gender roles and spheres, at least rhetorically, Kimball here resists them, saying that they are not enough for women to do what God wants them to. Love uncovering little quotes and insights like this.

A side benefit of Park’s insistence on the many Mormonisms always present is the way it often leads him to draw attention to the constructed nature of various figures’ ideas about the past. One such figure is J. Reuben Clark. Park writes, “Clark’s message was not so much a faithful reconstruction of a Mormonism once lost but a selective interpretation necessitated by the modern world. This creative reimagining of the faith was in line with the broader American fundamentalist movement” (240). I have believed this to be true about various conservative and progressive and all other Mormonisms, but to see it so clearly laid out here was refreshing. Too often, I see people cede ground to more ‘conservative’ elements, but here, Park explicitly names that these interpretations are often built and selective, just like their more ‘progressive’ counterparts.

Another anecdote that was new to me related to the lifting of the temple and priesthood restriction in 1978. Park writes, “Those involved later referred to the two-hour gathering as a spiritual Pentecost. All present provided unanimous approval for Kimball’s proposal. (Two of the apostles who had been outspoken in defending the restriction were absent: Mark Petersen was on assignment in South America, and Delbert Stapley was in the hospital)” (311-12). Interestingly, digging into the footnotes and reading Edward Kimball’s essay cited here by Park, reveals that Petersen pointed Pres. Kimball to an article about the restriction (probably Lester Bush’s landmark article). This raises even more questions for me about the way these various church leaders thought about themselves, their own private beliefs, and their public statements. The logistics are also provocative as a case study of revelation and determining who should or should not be present. A small microcosm of the many Mormonisms present here and everywhere.

American Zion will be an invaluable resource for me and others wanting a heavily researched and citation-filled vision of Mormon history in its entirety. Some readers will wish Park was more deferential to or open to the possibility of divine guidance or intervention in the Church and its practices and policies. I found Park to be remarkably fair and often quite gracious to the Church as an institution and collection of people, and think it would be very possible to read Park’s text allowing for the reality of revelation and divine guidance. Park, like the historian he is, simply tables those questions and lets the reader bring them to the text if they want. The final chapter is one of the most difficult to assess, as our proximity to its events makes determining what is or will be significant even more challenging than usual! I would likely have crafted a slightly different (arguably more hopeful) narrative towards the end, but only time will tell how Park and I are right, wrong, and somewhere in between.

I am thrilled for more people to get their hands on American Zion and begin to wrestle with Park’s vision of the many Mormonisms. May we work to honor the best of our past, make restitution for the worst, and otherwise put our shoulders to the wheel alongside our Mormon forbearers to bring forth truth.