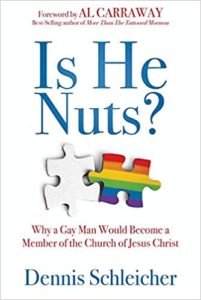

Title: Is He Nuts? Why a Gay Man Would Become a Member of the Church of Jesus Christ

Title: Is He Nuts? Why a Gay Man Would Become a Member of the Church of Jesus Christ

Author: Dennis Schleicher

Publisher: Cedar Fort

Genre: Memoir

Year Published: 2019

Number of Pages: 162

Binding: Hardback

Price: $22.99

Reviewed by Adam McLain for the Association for Mormon Letters, March 30, 2020

At times nonsensical and abrupt, Is He Nuts? Why a Gay Man Would Become a Member of the Church of Jesus Christ is Dennis Schleicher’s memoir of conversion and dedication to a Savior and God who loves him—even though he is gay. Schleicher’s story covers a lot of ground in a little more than 150 pages. He discusses abuse at the hands of his mother, a hate crime in high school that launched him into media fame as an advocate against abuse based on sexuality, his struggle with evangelical Christianity, and his life working for various MLM-like companies, finally landing in his current career for an unnamed MLM based in Utah. The story itself is raw in all senses of the word—literarily, linguistically, emotionally, and theologically. It’s a simple tale, when it comes down to it, of someone who has been told all of his life that God cannot love him because of his sexuality to his entering a world and a church that affirms God’s love for all.

This book, in and of itself, helps elucidate a niche part of our culture: the late-in-life convert who does not fill the idealistic heterosexual mold. It is wonderful to get a text that provides that voice because it is a minority voice. At this time, I cannot think of any other text that depicts the process of someone who has already gone through the coming out process and subsequently joined the Church. This book has merit in its uniqueness and its positive attitude toward the subject. Schleicher portrays the gospel as an excited convert would: full of wonder, full of grace, and full of love.

And yet, a voice filled to the brim with positivity and optimism cannot diminish the work Schleicher is attempting to do in his project. This is not to say that positivity and optimism are necessarily bad; it is to say that that type of voice, when not tempered with the reality of the situation, is prohibitive to the growth, engagement, and repentance needed to help a Zion grow. A book like this one that only allows people to reaffirm the goodness of the gospel and the Church only helps to stagnate Latter-day Saints in their understanding of how sexuality and spirituality converge in Mormonism.

Indeed, this book loudly proclaims a lack of awareness and self-awareness. Schleicher’s core argument is that the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is the best church for people who are gay because it teaches, at least in his understanding, that God loves him even if he is gay: or, in his words, “I’m just Dennis, who happens to be gay and happens to be Mormon at the same time” (137). This separation of homosexuality from God’s love and theology—that God loves someone, even if they are gay, rather than God loving someone because of their sexuality—shows the limitations the current perceptions of the gospel and the Church have on a person’s sexuality. Does God love a person, even though he or she is heterosexual? Definitely not in a church that must constantly utilize an amicus brief to reassert God’s firm repudiation of a person’s sexuality and affirmation of the idealized and idolized nuclear family. God loves them and even promises innumerable blessings because of their action upon their heterosexual identity and attraction.

Other problems with the text abound. For example, in examining parts of LGBT culture (at least, a mainstream, monolithic, stereotyped cultured), Schleicher enters the territory of a “holier than thou” voice, in some ways mocking the same LGBT people he claims to be an advocate. I recognize it is difficult to write a book geared toward a Latter-day Saint audience and to keep that book in the realm of Latter-day Saint moral purity; however, one does not find the respect for the culture and community he seems to disdain that an “advocate” (a title Schleicher uses for himself page over page) should have. Furthermore, Schleicher attempts to paint his memoir as a dramatic play by giving us the stage and the theater without the scenery, characters, or plot. The haphazard way the story is told hurts its literary quality along with the ability for the reader to actually understand what is happening.

While I raise a harsh critique of the book, Schleicher’s life is a truly uplifting story of someone finding a place in the circle of God and affirming to themselves the love that that Being has for them. I just wish Schleicher had been more aware in the telling of it—aware of the effect a book like this might have (e.g., I can see parents using it on their child who has been raised in the Church as a way to coerce them to stay or back into it), aware of the current ripples in Latter-day Saint theology (e.g., what does it mean to say, theologically, that God loves me, even though I’m gay?), and aware of the space his book fills (e.g., that of the converted gay man, but lacking the nuance those terms require to listen, learn, and love from).

At times, this book seems to be arguing that the entire Church is not homophobic and is even the best place for people who are gay. Without nuance, these statements slow the effort and progress that is being made as Latter-day Saints come to a full awareness of the harm, pain, and death the gospel and the Church have caused in its crusade against homosexual people. This book holds a place in Mormon literature, but it is this reviewer’s opinion that hopefully that place will be filled soon by a book that can provide a positive view of converting to the Church, while also appreciating and navigating the treacherous waters of conversion, sexuality, and spirituality.

Thanks Adam, that was a fascinating review.

Do you have an opinion about Tom Christofferson’s “That We May Be One: A Gay Mormon’s Perspective on Faith and Family”? I’m sure it is a better book than this, but did his experiences and suggestions ring true to you?

AML gave it the 2017 Creative Non-Fiction award, but I’m interested in what other Gay Mormons thought of it.

https://www.associationmormonletters.org/2018/03/2017-aml-awards/

I do have many thoughts on Christofferson’s text. I think it’s a decent text that has, on a positive note, allowed and provided acquiescence for parents to love their homosexual children. It’s sad that an entire book needed to be put out there to give that permission, but it is a positive thing that has come out of it. For example, I’ve had friends whose parents, after reading the book, allowed their child’s significant other to finally be discussed at the dinner table and even invited over for dinner.

However, I found it severely harmful in two ways. The first is Christofferson’s subsumption of the LBTQ+ part of the queer communities. In many ways, his text doesn’t parse between his experience as a at-least-middle-class, white, cisgender male and all the other forms of identity that the queer communities represent. Whereas Christofferson decided to use LGBT to mean the entire community holistically, I find it much better to use terms like LGBTQ+ communities, in the plural, to show that even the queer community as a collective is not homogenous. In creating that homogeneity, Christofferson applies a lot of his own experience onto other forms of identity that he knows only cursorily about; and in doing so, he doesn’t show his audience how to parse apart the communities that make up Greater Queerdom.

The second issue I have is how Christofferson’s text can be used. It gives parents a hope that one day their queer child will return to the Church. That’s a fine hope to have, but a lot of Latter-day Saints base their love on their child then on what their child might become rather than who they are in the moment. This is a pernicious type of love because it’s a love of expectation rather than a love of reality. Christofferson’s text gives that hope because it’s his own return to the Church. Yes, Christofferson complicates it a little and shows, briefly, his oscillation with the Church and how it is fluid, but in essence, the text is providing parents that thing to hold onto so they can love what their child might become.

Additionally, the text shows no loss for Christofferson’s 19 years of life with his partner. He explains that he wants to respect his partner’s privacy, but there is no sadness in the text or sense of loss, which I think could have been a great boon to Latter-day Saint communities: to see how to mourn the loss of a queer relationship that it takes to return to or convert to the Church. It’s so ungodly for members of the Church to not mourn and weep over the loss of a loving, caring, and positive relationship, even if it doesn’t fit the “morality” they seem to espouse. I believe there has to be room in the Church for members to collectively mourn what is lost when joining, while simultaneously rejoicing at a person entering a covenant with God. Weeping over that loss does not diminish the great happiness from that covenant; however, ignoring the pain and not addressing it does cause a disillusionment from reality to occur. So, when Christofferson simply shrugs that part of his life off like it is nothing, it makes it nothing. And that was 19 years of his life that shaped who he is that the reader suddenly cannot understand or comprehend when seeing Christofferson as a full child of God.

So, with Christofferson’s book, I agree with you that it is a better book than Schleicher’s. It’s well written and deals with the broader theological significance; it just doesn’t go as far or as deep as needs to happen for the Church to actually start addressing the overarching issues it has with homosexuality and queerness. Christofferson’s and Schleicher’s books are okay starts to that process, but there needs to be an outpouring from the windows of heaven for the Church to even begin to scratch away at the bloodstains on the temple steps.