Review

———

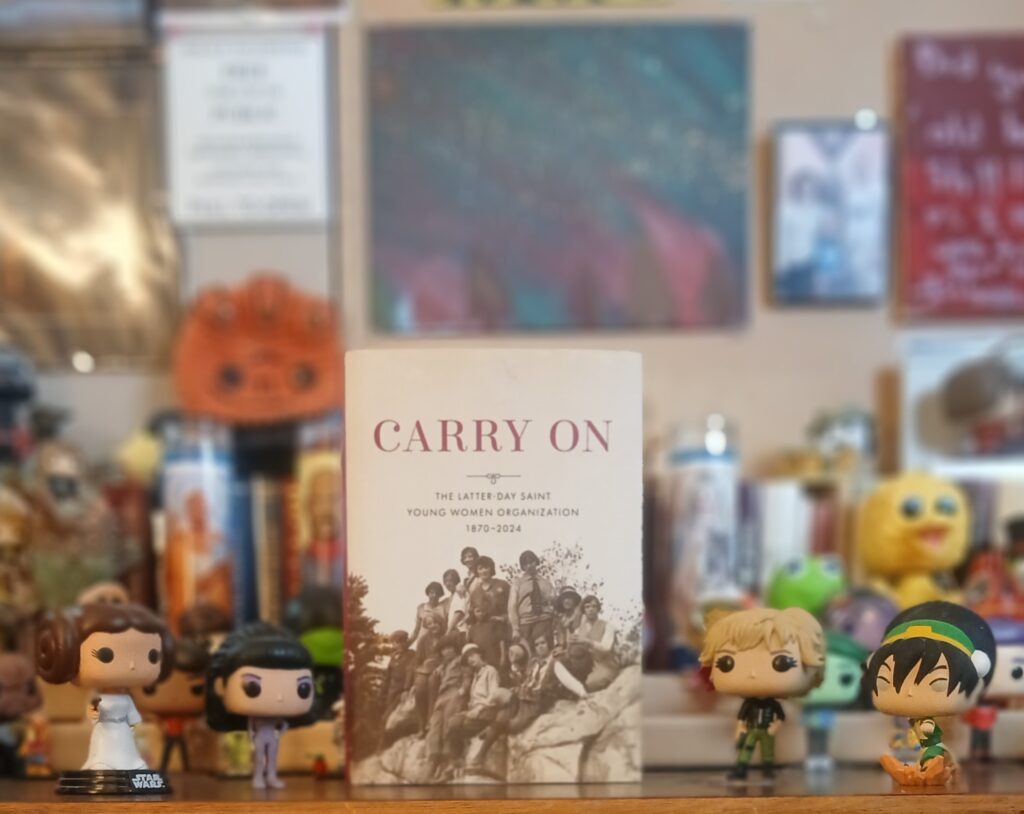

Title: Carry On: The Latter-day Saint Young Women Organization, 1870–2024

Author: Lisa Olsen Tait, Amber C. Taylor, Kate Holbrook, James Goldberg

Publisher: Church Historian’s Press

Genre: Non-fiction

Year Published: 2025

Number of Pages: 448

Binding: Hardcover

ISBN: 978-1639933747

Price: $34.99

Reviewed by El Call for the Association for Mormon Letters

Carry On is a thorough history of the Young Women’s organization in the LDS Church. It is engaging, dense with stories and history, and a prime example of what is needed for all other Church organizations.

The book breaks the history down into three eras: “The Youth of Zion (1870-1930),” “True to the Faith (1930-1984),” and “Daughters of Heavenly Parents (1984-2024).” This book does an excellent job of providing first-hand accounts to illustrate the greater institutional history. Many of the stories focus on young women from outside of the United States, sharing how various programs worked for them and strengthened their testimonies—or didn’t. I enthusiastically earned both my Personal Progress medallion and the Honor Bee award primarily during Elaine S. Dalton’s presidency. Even so, I struggled with why certain decisions were made regarding these programs; this book reshaped my understanding.

Many of the decisions made by leaders of the Young Women’s Organization were contextualized by information on the contemporary American milieu. These additions provide necessary grounding in time and culture, suggesting why leaders focused on particular topics. Similarly, comparisons to the actions of the Young Men’s organizations provide a contrast to how a different auxiliary functioned within the Church.

Carry On is well-sourced with copious footnotes, making it easy for researchers to build on this work. This book has the potential to spark significant research that I look forward to seeing in the future. (For example, an examination of how the Young Women organization appears to have prioritized autonomy while the Young Men organization seems to have prioritized stability when considering partnerships with other organizations.)

I learned so much from this book; my personal copy is now filled with sticky notes, underlines, and exclamation points. I found connections to at least three wildly different projects that I’m currently working on, with new avenues to explore and sources to consult. Sections of the book addressed historical concerns and issues that feel extremely relevant to the present situation. Among them:

- A discussion of changing fashions in the 1910s and 1920s that led to the modification of garment styles. “Ultimately, church leaders found ways to accommodate most of the changes in fashion. After a period of prayer, study, and discussion, senior church leaders concluded that the symbolic meaning of the garment, the principles it represented, and the covenants it reminded wearers to keep were more important than its specific form. It could be redesigned to be less cumbersome and more in keeping with changing dress styles. In 1923, they authorized a new design for both women and men with shorter sleeves and legs and a lower neckline” (p. 82).

- Youth wanted “the church to take a more active approach to dealing with the economic devastation occurring all around” (p. 118) and generally not feeling that the Church was providing them what they needed (p. 118-119).

- Church leaders grappling with “how to balance support for local initiative and adaptation with a desire for more consistency and uniformity” (p. 171).

More than anything, I was struck by learning about the first-person statements written for the Young Women’s Values during the tenure of Ardeth G. Kapp. These were to be affirmations, I-statements that corresponded with each of the seven values. The revised draft that I grew up with reads, “I am a daughter of Heavenly Father, who loves me, and I have faith in His eternal plan.” The original draft read simply, “I am a daughter of Heavenly Parents.” A lack of explicit scriptural teachings on Heavenly Mother led the correlation committee to recommend changing the language toward something that could be accompanied by a scriptural citation like the other values statements (p. 244-245). While I’m not entirely sure how much I would have been affected as a teenager to have been able to recite and affirm the existence of Heavenly Parents, I do know that I’m affected now by that lack. It makes me grateful, at least, to know that the leaders tried, even if they were ultimately overruled.

If I had my say, I’d put a copy of Carry On in every Church library resource center and encourage the local Young Women’s organizations to use it for discussions. I would also recommend it for male Church leaders at every level; many of the female leaders quoted in the book talked about how hard it was to convince the men of the Church that the women—the young women especially—were worth listening to. Carry On focuses on institutional priorities, but the young women quoted throughout the book clearly express their desire to be taken seriously.

As someone who is currently working on a similar history of the Sunday School program, I was both encouraged and overwhelmed by the amount of time and work dedicated to writing Carry On. After reading this, I feel, more than ever, the necessity of writing such a history for all of the Church organizations. The current president of the Young Women’s Organization, Emily Belle Freeman, shared how she was provided with a manuscript of the book when she was first called. Learning more about historical decisions shaped how she made decisions for the current organization. Given the reduced time spent as general officers, all organizational leaders deserve the same opportunity to have easy access to their history.