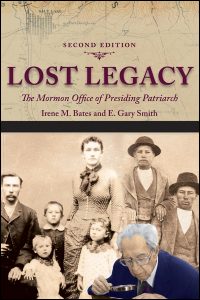

Title: Lost Legacy: The Mormon Office of Presiding Patriarch (Second Edition)

Authors: E. Gary Smith and Irene M. Bates

Publisher: University of Illinois Press

Genre: History

Year Published: 2018

Number of Pages: 276

Binding: Paper

ISBN: 978-0-252-08309-9

Price: $29.95

Reviewed by Andrew Hamilton for the Association for Mormon Letters

At the beginning of the Saturday afternoon session of the October 1979 Semi-Annual General Conference of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, President N. Eldon Tanner stood at the tabernacle pulpit to follow the traditional Mormon practice of “sustaining” the Church leaders and officers. But before performing the sustaining he read the following:

“Before presenting the authorities for the vote of the conference, President Kimball has asked me to read the following statement: Because of the large increase in the number of stake patriarchs and the availability of patriarchal service throughout the world, we now designate Elder Eldred G. Smith as a Patriarch Emeritus, which means that he is honorably relieved of all duties and responsibilities pertaining to the office of Patriarch to the Church.”

He then continued on with the usual releases and sustainings with the following coming up right after sustaining Spencer W. Kimball as trustee-in-trust for the Church and right before the sustaining of the First Quorum of the Seventy:

“As Patriarch Emeritus, Eldred G. Smith. All in favor, please manifest it. Contrary, if there be any, by the same sign.”[1]

For almost 146 years, from December 1833 to this announcement in October 1979, this office of “Presiding Patriarch” or “Patriarch to the Church” (the name of the office with all of that name’s implications was a cause of dispute over the years and the designation changed as documented in this book) existed as one of the most important offices in the Church. For much, though not all of, that time the holder of the office, like the members of the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, was sustained by Church members as a “Prophet, Seer, and Revelator” (this was also a point of controversy, as documented in this book). Just where this priesthood leader sat on the stand and when his name was to be read during the sustaining of general authorities sometimes changed and was another cause of dispute over the years (you guessed it, see the book for more!). But during these 146 years, health and attendance permitting, the Church Patriarch was always in a very prominent position on the stand in General Conferences.

When this change took place in 1979 the LDS Church had a total membership of 4,439,000. At the end of 2017 the Church, according to its own records, had 16,118,169 members. That means that, not accounting for births and deaths since 1979 (sorry, that’s way too much algebra and statistics for me) there are at least 12,000,000 Mormons who were not yet born or who had not yet joined the Church when President Tanner read the subdued yet historic announcement that, for all intents and purposes, ended the office of Presiding Patriarch. To put it another way, at least 75% of current Church membership did not exist when this important change occurred. It is likely that many or even most of these “new” members do not even realize that the position of “Patriarch to the Church” even existed.

I was six years old when the Eldred Smith was given “Emeritus Status.” To my memory I never learned about Eldred Smith or the office of Church Patriarch growing up; rather, I first learned about him and the existence of his office/former office when I was reading through old General Conference issues of the “Ensign” magazine when I was on my mission in Oklahoma in 1992. I quickly became fascinated with this office that had once been considered a “Prophet, seer, and revelator” and wondered why, as important as his calling seemed to have been, there was not then someone serving in the office. I asked my mission president and various missionaries and local members of the Church about it, but no one could tell me more about Eldred Smith, the office, or why it had stopped. I tried to read more about the Church Patriarch both on my mission and after I got home, but I learned very little as there were just no resources for learning this information at that time.

Then in 1996 the University of Illinois Press published E. Gary Smith (the son of Eldred Smith), and Irene M. Bates’s award winning book Lost Legacy: The Mormon office of Presiding Patriarch[2]. I first read Lost Legacy soon after its initial release. This important book quickly became one of my favorite Mormon history books and was one of the books responsible for my love of Mormon history, especially the “New Mormon History.” Since the office of Church Patriarch is not mentioned in any Sunday school lessons or standard church materials currently available to average LDS Church members, and since it is becoming less likely as time goes by that someone would casually pick up an old Ensign from the mid 70’s (as I did) and learn of the office of Church Patriarch, the only way for someone to really learn of the office of “Presiding Patriarch,” its history, its controversies, and of the eight men who held this office, is by reading Lost Legacy. Unfortunately the clothbound version that I loved so much has been long out of print and even the later paper reprint occurred many years ago.

With the recent passing of Eldred Smith and Thomas Monson (the last of the apostles serving when Smith was made emeritus), with the passing of time since the office of presiding patriarch was discontinued (from approximately 20 years to nearly 40), and with a growing generation of Mormons who may not even know that a general authority office once considered a “prophet, seer, and revelator” no longer exists, Lost Legacy is a very important book to read and share, maybe even more important than it was in 1996. Fortunately for everyone interested in Mormon history, the University of Illinois press and E. Gary Smith (Irene Bates passed away in 2015) have published this second edition of Lost Legacy that incorporates a new Preface, a chapter covering the “Emeritus Years” of Eldred Smith, the last Church Patriarch, and some updated footnotes.

For those who have not read the first edition, Lost Legacy is the story of the office of “Presiding Patriarch” and focuses on the history of that office and the controversies surrounding its creation, its existence, and its demise. With that history you get some of the biographical story of the eight men who held the office, though this is not the focus of the book. The foundation for the book, and the theories presented by the authors as to why the office was so controversial, are laid down in the first chapter, “Charisma and Authority: The Crucible for the Office of Patriarch.” In this chapter Bates and Smith discuss the theories of different types and phases of authority as put forth by Max Weber, show how they connect to the stages of development that the LDS Church has passed through, and explain how these different “Weberian Types of Authority” are seen in the LDS Church and how they are exhibited in the conflict that existed between the office of “Presiding Patriarch” and the members of the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve.

The next eight chapters deal with each of the patriarchs individually and go into great detail about the history of the office during that man’s tenure including the conflicts and tensions that existed between the office holder and the other general authorities. The new final chapter is chapter 10, “Unique Emeritus: Eldred Smith – Patriarch/General Authority Emeritus, 1979-2013.” A conclusion then wraps up the story, followed by several appendices that add other relevant information.

If you have never read Lost Legacy, this book is a must read. I know that phrase gets used a lot, but this really is a must read book for those interested in Mormon History and theology. Bates and Smith explain how the office of Presiding Patriarch was one of the earliest offices created in the LDS Church, predating the quorums of 70 and the Quorum of the Twelve. For a very long time the office holder was sustained as a “prophet, seer, and revelator” just as the Quorum of Twelve and First Presidency are. John Smith, the fifth patriarch and son of Hyrum Smith, set his half-brother Joseph F. Smith apart as the sixth president of the LDS Church in 1901 (see chapter 6).

Speaking of this office and its importance, Joseph Smith said that his father and his descendants would hold “the keys of the patriarchal priesthood over the kingdom of God on earth” and that “whenever the Church of Christ is established on the earth, there should be a patriarch for the benefit of the posterity of the saints.” Brigham Young added that:

“it was necessary to keep up a full organization of the Church through all time as far as it could be. At least the three first Presidency, the quorum of the Twelve, Seventies, and Patriarch over the whole Church &c so that the devil could take no Advantage of us” (see page 5).

When Joseph Smith Sr. was set apart as patriarch, Joseph Smith said that he “and his seed after him” would have this calling “to the uttermost” (see page 7). Other quotes outlined in the book also show how it was taught that this office would always need to exist in the LDS Church and that the descendants of Joseph Smith Sr. would always hold it. The authors then document in great and fascinating detail how, despite these statements, after the death of Joseph Smith Jr. there was nearly always controversy and conflict surrounding this office up until the time that Spencer W. Kimball and his councilors eliminated it by designating the eighth and final patriarch, Eldred G. Smith, “Emeritus” and then never replacing him. If you have any interest in the power dynamics that exist between the presiding quorums of the LDS Church, what happens when members of those bodies disagree and have conflict with each other, and how they come to some of their decisions before they announce them to the body of the church as revelations, then Lost Legacy is the book for you.

If you own or have read the first edition, you may be wondering if it is worth the investment in time and money for you to read or purchase this second edition. My answer is yes, the new last chapter on the “Unique Emeritus” years of Eldred Smith is absolutely engrossing. While it only adds about 18 pages to the text, this chapter is a very important read. In it E. Gary Smith documents how it was the office of Presiding Patriarch itself rather than Eldred Smith the man that was given emeritus status. In the chapter he briefly describes the history of “Emeritus status” in the LDS Church, how it applied to the men who had been Seventies, and just how different Emeritus Status was for Eldred. It provides more background information including a letter from the Quorum of the Twelve to the First Presidency in 1949 outlining their concerns with the functions of the Presiding Patriarch and the scope of his office.

E. Gary Smith then tells the story of how, until nearly the day that he died at the age of 106, Eldred Smith continued to have an office at LDS Church Headquarters, continued to give patriarchal blessings, and perhaps most importantly, how he travelled around the world giving firesides to LDS audiences. In these firesides he would tell the story of the restoration focusing on Hyrum Smith. As a part of these firesides he would exhibit Smith family artifacts including the clothes worn by Hyrum Smith when he was murdered and a box once owned by Alvin Smith that the Gold Plates were said to be kept in for a time while Joseph Smith was translating them. Reproductions of general authority charts and photos in this chapter also help to tell the story. It’s an important and informative chapter and now that I have read it I can’t picture Lost Legacy without this interesting additional information.

The updates and additions that Gary Smith made to this book are a great help and add important dimensions to the story. With what was added and how it enhanced the story of Lost Legacy, I was a little surprised at a few of the resources that were not incorporated into this updated version of the book. The first resource that could have added more dimension to this second edition of Lost Legacy, even if just in the footnotes, is the Joseph Smith Papers Project. In chapter one, which is the chapter on authority types that I previously mentioned, the evolution of authority in the LDS Church and how it affected the office of Presiding Patriarch is discussed in detail. On page 16 the authors highlight changes made in the revelation now known as LDS Doctrine and Covenants 68. They point out that this revelation originally spoke of the “presiding authorities” in the Church as being “a conference of high priests,” but by the time the revelation was printed in the Doctrine and Covenants it had been reworded to say “the First Presidency of the Church” in place of “a conference of high priests.” The footnote for this change references a D. Michael Quinn Journal of Mormon History article from 1974, a Marvin Hill BYU Studies article from 1969, and a talk by Greg Prince at the Mormon History Association Conference in 1992. These are all great resources and it is an excellent footnote. As great as it is, it would be a much better footnote if Smith had incorporated in it information made available in the Joseph Smith Papers: Documents Vol 2 which contains this revelation with an essay and footnotes that dissect and analyze it in detail on pages 98-103 of that volume.

This may seem like a petty observation on my part, and maybe no one else is nerdy enough to look at the footnotes with that kind of attention, but the “Preface to the Second Edition” mentions that this version of the book contains “footnote additions” (p. vii) and this is one that I think would have made a strong book even stronger.

I saw a second missed opportunity in this Second Edition in relation to the story of the Seventh Patriarch, Joseph Fielding Smith II (how he is referred to in the book). This Joseph Fielding Smith served as Patriarch to the Church for a brief time from 1942-1946. He was the grandson of the first Joseph Fielding Smith, usually called “Joseph F.”, who was the sixth president of the Church through his oldest son Hyrum (who served as a member of the Quorum of the 12 from 1901-1918). He should not be confused with his uncle Joseph Fielding Smith the apostle who was the son of the first one and who would later become the tenth president of the Church (those Smiths loved to reuse names!). I thought that this was one of the most interesting and important chapters in the whole book. Bates and Smith did an excellent job of telling and documenting the fascinating story of the “Decade of Uncertainty and Compromise” that occurred in the highest levels of the Church after the death of the sixth patriarch and then briefly tell of the unfortunate circumstances that led to the seventh patriarch’s short term of service.

Bates and Smith write of how when the sixth patriarch Hyrum G. Smith (I told you those Smiths liked to reuse names!) died in 1932, President Heber J. Grant tried to reorganize how the patriarch was called. Instead of calling Hyrum’s son Eldred, who traditionally would have been the new patriarch, Grant wanted to switch from the John Smith family line (Hyrum’s oldest son and the fifth patriarch) to the Joseph F. Smith family line. Not only did Grant want to switch family lines, what he really wanted his son-in-law, Willard Smith, to be the new patriarch (see pp 180, 187, 190). The Twelve, led by George Albert Smith and Joseph Fielding Smith, balked at this change and pushed for their cousin and nephew Eldred Smith to be called to the office as tradition and the teachings of past leaders seemed to dictate. Grant refused to back down and so did the Twelve. Neither side was willing to compromise. For 10 years there was a standoff and no patriarch was called.

Finally both sides budged some and Joseph Fielding Smith II was called instead of Willard or Eldred Smith. It really is a fascinating story and Smith and Bates tell it well and provide great footnotes that give their sources and enhance the text. Living in a time when it is common to hear Church presidents tell about the unanimity and harmony between the First Presidency and the Twelve, and how this reflects on the truthfulness of the Church and the level of revelation and brotherhood that these men enjoy, it is an interesting study that will likely shock many modern LDS members to read of a time when these men had a decade long disagreement.

As much as I loved this chapter, two sources not available when the book was written in the 1990’s that were not utilized this time could have enhanced this already great book. When the book came out in 1996 Smith and Bates did not have much evidence that they could cite to prove that Grant wanted to call his own son-in-law to be the patriarch. If you go to the original footnotes for this chapter, this historical point is made based on reported Smith family conversations. In the 20 years since the book’s initial release, excerpts from the Heber J. Grant diaries have been made available for research that confirm and add detail to the story of how Grant tried to have Willard Smith installed into one of the highest office in the Church. A quote from these excerpts appeared in the book Later Patriarchal Blessings of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints[3]. This quote was added as a part of footnote 37 in this chapter (chapter 8). In it Grant explains that Eldred came over to his home after the decision to call Joseph F. Smith II was made. Grant told Eldred that he was worthy to be called, but that someone else had been chosen. Eldred said that he was disappointed but would support the brethren. Grant ended the entry by stating that it was a miserable night for him. It’s a great excerpt and really adds to the book. What surprised me, and what I felt was a loss to this edition, was that Smith did not use more excerpts from Grant’s now available diary that flesh out and support the story of his attempt to call his son-in-law Willard to be Patriarch. Here are a few lines from some those excerpts that in my mind could have really fleshed out this chapter:

“George F. Richards, David O. McKay and James E. Talmage called and made a report that they thought it would be a serious matter to have Eldred Smith made the Presiding Patriarch. … We discussed the propriety of changing and having one of Joseph F. Smith’s sons made the patriarch. The names of Calvin and Willard R. Smith were suggested. My own impression is that it is almost providential to have a faithful, diligent outstanding Latter-day Saint grandson of Hyrum Smith made the patriarch instead of having a great great-grandson of Hyrum Smith through the line of John Smith. We discussed the matter until nearly seven o’clock [March 29, 1932].”

“David O. McKay called the first thing this morning and we had a still further talk with him regarding the appointment of a patriarch. I told him that personally I would like to see my son-in-law made the patriarch … [March 30, 1932].”

“Attended the regular weekly Council meeting of the Presidency and Apostles in the Temple. … had a long discussion about filling the vacancy caused by the death of Hyrum G. Smith as Presiding Patriarch. There was quite a difference of opinion. Some of the brethren felt that Hyrum G.’s oldest son should be appointed, others that Calvin Smith, …and others that Willard R. Smith, my son-in-law. No decision was reached [March 31, 1932].”[4]

I’m not sure why this information wasn’t used. I think that it would have strengthened an already great chapter of the book. Maybe Smith was not aware it was available and only knew about the quote in the Later Blessings book. Maybe he knew of them but did not feel that they added to the book. I suppose that I will never know, but it would be interesting to ask him about these entries. Other diary entries by Heber J. Grant add to the story as well, including the entries for October 10, 1942 and February 27, 1943, which give more information after Joseph F. Smith II was called to be the Patriarch. Those who have access to these diary entries should consult them as they really add to the information in this chapter[5].

One more recent source, this time a secondary one, if mentioned, would have also added to this chapter and the story of Joseph F. Smith II. Heber J. Grant and other members of the First Presidency said that Joseph Smith II’s calling as Church Patriarch was “inspired” and revelation (see p 192). Despite this revelatory endorsement, he only ended up serving as Patriarch to the Church for four years before being the only Church patriarch to ever officially be “released.” Before this time all of the incumbents died in office. The official reason given in General Conference for Joseph Smith II’s release was that he was in poor health so he volunteered to be released so as to not hinder the important work of the office of the patriarch (see page 195). This, however, was something of a cover story. While he may have been experiencing some health problems, at the end of this chapter Smith and Bates briefly document the real reason for Joseph II’s release. It turns out that there were “allegations of some involvement in homosexual activity” involving Joseph F. Smith II that came to the attention of the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve. These allegations were proved and the presiding brethren felt that this disqualified Joseph F. Smith II from further service in this office (pp 193-196).

In 2012, the Journal of Mormon History published a 32 page article by Gary Bergera called “Transgression in the LDS Community: The case of Joseph F Smith.[6]” In this article Bergera greatly fleshes out the story of Joseph F. Smith II’s life, of the possible homosexual activity that he was involved in, how this came to the attention of the leaders of the Church, what happened that led to his release, and of the aftermath of his release. Lost Legacy, while including some of the story of the men involved, is ultimately the story of the Office of Patriarch, and not a biography of the men who served as patriarch. Because of this I can understand why this story was not told in more detail in the main text. As interesting as the story of Joseph F. II’s homosexuality is, spending too much time on that story could have distracted from the purpose of the book. So I understand why this story was so briefly told in the main text of the book. However, I think that it is an important enough story that a footnote leading readers to Bergera’s article would have made this a better chapter and a better book.

I realize that I went into a lot of detail explaining my last two points. *PLEASE* do not let this make you think that you should not read this book or that I think that it has major problems or even any minor one! I cannot say enough how important this book is or how much reading it influenced me. I know that I repeated my praise for this book over and over again in this review, but it is deserved, Lost Legacy is an important book about a fascinating and crucial part of Mormon history. I was in the middle of writing this review when the LDS Church in its April 2018 General Conference announced a major “restructuring” of Melchizedek Priesthood quorums involving the elimination of High Priest Groups in the wards and branches and the integrating of the men in these groups into the ward and branch Elders quorums[7]. This announcement led to a great reaction in LDS wards and on social media. I have heard many people express curiosity and wonder as to the process involved in making this decision. While we may never get the full details of the council meetings, discussions, decisions, and presumably revelations involved in making this current priesthood change decision, I would encourage everyone who wants to know more about this current change to read Lost Legacy. The story of the creation and eventual dissolution of the office of Presiding Patriarch as told by Smith and Bates provides something of a parallel story to the changes being made in the priesthood of the LDS Church right now.

While the situation is not exactly the same, reading about and gaining insights on how and why the presiding brethren decided to eliminate a general authority level office that once upon a time was sustained as a “prophet, seer, and revelator” will not only help the reader to understand the history of the LDS Church better, it will help them to better understand the current LDS Church and its decision making processes.

[1] Text and audio available at https://www.lds.org/general-conference/1979/10/the-sustaining-of-church-officers?lang=eng

[2] Winner of the Mormon History Association Best Book Award, 1997.

[3] Compiled by H. Michael Marquardt, published by the Smith Pettit Foundation, 2012.

[4] Excerpts from The Diaries of Heber J. Grant, 1880-1945, Abridged, Digital Edition Salt Lake City, Utah, 2015 – see also the entries for April 1, 1392; April 2, 1932; March 23, 1933; September 26, 1935; and April 7, 1937 These excerpts were originally printed in a limited edition clothbound copy in about 2010. In 2015 they were released in digital form, bundled with other journals and records, as The Prospect of Ready Access: Annals of the Apostles 1835-1951. This is available at Benchmark Books in Salt Lake City for $75.00. https://www.benchmarkbooks.com/ Some excerpts are available at the blog “Today in Mormon History” http://www.todayinmormonhistory.com

[5] If you do not have access to the cloth or digital versions of Grant’s diaries, I really do encourage you to go read the excerpts on the subject of Heber J. Grant’s desire to call Willard Smith as Patriarch to the Church at the blog http://www.todayinmormonhistory.com

[6] Pdf version of the entire issue of the Journal of Mormon History containing this article available at https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol38/iss1/1/

[7] See https://www.lds.org/general-conference/2018/04/introductory-remarks?lang=eng

I’ve read the first edition multiple times, to the point that I read the above information with great interest, as a point of curiosity I lent my copy to a serving Patriarch who read and then reread it so many times that I eventually told him to keep it as he never stopped reading it.

I was 6 when Eldred was released and much like the author of this article I miss something that I never knew when it existed.

I’m glad that Gary has updated the book, I very fleetingly corresponded with him and Irene Bates to compliment them on the book. Like the author of this article I very much recommend the book.