Review

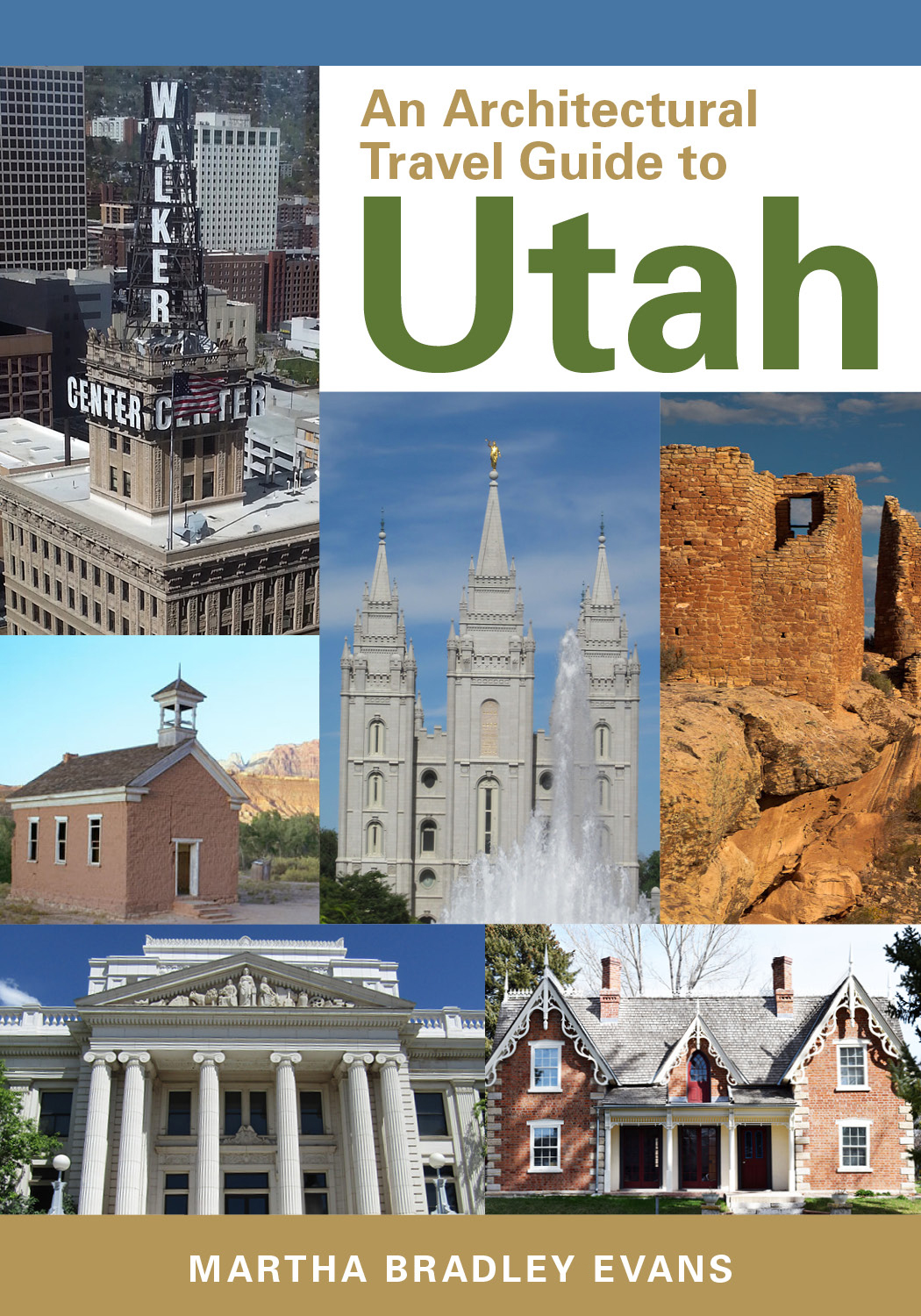

Title: An Architectural Travel Guide to Utah

Author: Martha Bradley Evans

Publisher: University of Utah Press

Genre: History and Travel

Year Published: 2021

Pages: 437

Binding: Paper; E-book

ISBN: Paperback, 9781647690083; ebook, 9781647690090

Price: Paperback, $36.95; ebook, $30.00

Reviewed for the Association for Mormon Letters by Julie J. Nichols

I was surprised by how much I liked An Architectural Travel Guide to Utah by Martha Bradley Evans, and I had a few shy ideas about ways it could be improved. As I age, I get more and more particular about what I spend my time reading, but I assure you, this book ticked all the boxes—reader-friendly, clean and attractive in design, informative, unexpectedly engrossing in content, and detail. Even so, as I read, I thought of a few things that might have made it even better.

There are a lot of ways to explore, especially places we think we know already. At first, we hear about a place. Maybe a friend recommends it (“Have you been to Hole in the Wall?”), or maybe we drive past it on the way to somewhere else (“Hey, I didn’t realize the Sundance Kid’s birthplace was on the way to Bryce Canyon!”). Then we decide to plant our physical selves at the place, take time for it, walk around in it, maybe touch it if we’re allowed, eat something there, talk to the folks who take care of it. Often it isn’t till after that that we begin to realize there’s much, much more to know about it: its layers of history, the psychology of the people who inhabit(ed) it, how it holds up in weather, how it came to be in the first place, what it turned out to embody.

Part of this later, deeper exploration has to do with architecture: the shape, size, location, and composition of the buildings that grace any place where people gather. In An Architectural Travel Guide to Utah, Martha Bradley Evans has gifted us explorers of the Mormon capital and its environs with a thorough, admirably-researched, intelligent, and, happily, color-photographed companion to our next-level explorations. If you’ve traveled around the state at all—even if you’ve only visited Salt Lake City—this book should be in your hands, now and the next time you venture out. It’s a gem.

The buildings of eight regions of Utah are described in brief but comprehensive detail. (We bow to Bradley Evans’s ability to be both brief and comprehensive. Brilliant!) The eight regions are Salt Lake City/County and seven groupings of counties around the state. Before she escorts us through these regions, Bradley Evans provides a readable, clear overview. An entertaining preface reminds us how built structures both express and create the energies of cities and towns, families and groups, and that there are many vantage points from which to approach them (the buildings, I mean). We can oversee their general tone from above; we can experience their vibe from inside; we can appreciate their material composition, the effort it took to gather and construct the walls and roof, and we can savor the philosophies that drove the people to build in just those ways.

In her “Context for the Guide,” she provides a concise overview of Utah history—if you think you already know it, she doesn’t burden you with repetition and unnecessary detail. There are also two equally concise sections on how and why she selected the buildings she did to describe and discuss, and what other books are available should we want to explore further through reading. This overview section—and all that follows—is lively and readable.

By the way, An Architectural Travel Guide to Utah (like most U of U publications) is designed to be reader-friendly; although it’s hefty, it fits in a backpack readily (I tried it), and the font, leading, and format are uncomplicated and easy on the eyes.

After the “Context” is an engaging section on Utah’s architectural history from the ancient inhabitants through white settlement, including the role of religious buildings in Utah’s evolution, the railroad’s impact on growth, and the inevitable movements away from Mormon hegemony toward a strong worldly-wise architectural community. She ends with a plea for preservation and awareness. Every paragraph held my interest.

And then there is the guide itself.

Salt Lake is the biggest section.

Now, here’s where I might make a suggestion. The sections are designated by colored tabs on the edge of the book. They don’t stick out like actual tabs (that would unnecessarily complicate the format), but each section is indicated by a tastefully small tab of color–purple, seagrass, salmon, etc. Thumbing through each section, we encounter a somewhat geographically-ordered set of descriptions, many with accompanying color photographs. One thing I missed and wished for, though, was some combination of index and map so that if I were driving around a location and saw a building that fascinated me, I could look up whether or not it was included in Bradley Evans’s guide and could turn directly to the page. She says upfront (in the “Context”) that she chose to highlight buildings that “are exemplary, that represent various trends, styles, or building technologies, or that illuminate particular themes,” and that many of the featured structures are on historical registers. Still, an alphabetical and/or map-connected index would facilitate our discoveries and heighten even more our pleasure in this book.

So, Salt Lake is the biggest section. It includes another brief historical overview, and then begins with the Marmalade District, moving through Capitol Hill, the Avenues, Gilgal Garden, Trolley Square, and dozens of other neighborhoods/structures of interest. For each, she provides the address, then describes original use, architectural style, and composition, sometimes original ownership, and sometimes the architect’s name. Not a single entry fails to amuse, divert, and inform. We could ride, drive, walk our way through Utah with this guide in hand and be quite enlivened and enriched.

Regions A through G are similarly organized: a well-written, engaging introduction gives way to as many points of call as Bradley Evans judges we should know about. And here is the second thing I missed and wished for, though I read every entry with pleasure: I wished I knew what’s happening with each building now. Of course, I know that the Salt Lake City Library is a center of the community as well as a haven for book-lovers these days; of course, I know that the St. George temple is still in use. But what about the Fenn/Bullock house in Uintah County (p. 289)? Is it still a residence, still in the Bullock family? Or the Joseph Wall Gristmill in Richfield (p. 349)—what’s it used for today? Anything at all? Can I bring my children to see it, are there pamphlets at the site (as I know there are at Gilgal Garden, for example)?

Undoubtedly Bradley Evans set boundaries as she made this book, recognizing the value of the historical information she intended to provide and stopping at tourist-type copy. But still. I’d have loved to know, as I drove through Juab and Sevier Counties the other week on my way home from a horse-camping trip in Fishlake, what buildings it would be fun to visit, and what I might expect when I found them.

I like exploring. I especially like exploring with knowledgeable company. Martha Bradley Evans’s Architectural Travel Guide to Utah is a fine gift for yourself or friends, whether or not you (or they) think they know Utah already. In more architectural ways than we realized, Utah really is a rewarding and fascinating place.