Review

Review

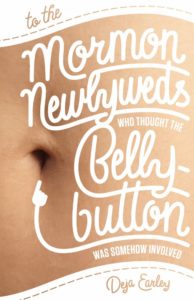

Title: To the Mormon Newlyweds Who Thought the Belly-button was Somehow Involved

Author: Deja Earley

Publisher: Signature Books

Genre: poetry

Year of Publication: 2018

Number of Pages: 71

Binding: paper

ISBN 978-1-56085-271-1

Price: $19.95

Reviewed by Julie J. Nichols for the Association for Mormon Letters

The poems in To the Mormon Newlyweds, if read in order from front to back, are a journey from Mormon childhood innocence about love/relationship/sex to lovely accepting maturity about those very same enigmatic, esoteric conundrums of mortal life. In a way the title means “To the Mormon children who will need to grow up: don’t worry, it’s all right; growing up is important; we all have to navigate that path; let me help you get there, let me show you what you’ll need to know…”

And of course “growing up” is not only about sex, as Earley puts it so poignantly in the title poem near the end of the collection:

“…sex in marriage is sex, but it also concerns the price of car insurance…//What’s/ sexiest is what’s on hand, transformed.//You move the cat aside, brush away a fleet of toys, and hope/you don’t wake the baby. Quietly, quietly, you make of every/ mundanity a room,//and the two of you enter it…” (61)

Earlier (pun, yeah), there’ve been poems from within childhood. Part I (no titles, just Roman numerals separate the Parts) describes a growing child’s uncomprehending introduction to—well—just about everything: Bunnies (when they wear bowties, they’re something else entirely);

Bugs (they do violence, violence can be done to them, and parents don’t get how wrenching that violence feels); Bees (heavy with unexpected honey). Then also church dances (“firstkissfirstkissfirstkiss”), relationships seen from outside (“She tells us he was watching TV when she called,/and I’m young enough to think this spells marital doom”), aging seen also from without. (This reviewer is old enough to have been disappointed by the poems about aging, but if seen as from the point of view of a young teenager, I shouldn’t be. Disappointed, I mean. Because the empty-nest parents are shown as empty-hearted, lonely, lost. That disappoints me, because we’re not—far from it. But the child doesn’t know that yet.)

Part II contains poems about those awkward not-yet-married-but-want-to-be young adult years. Even when they’re about considering what color the speaker would give up if forced to by alien abductors, these poems are about longing for relationship: “They can forget about purple/because of the dress you like me best in…//The aliens mill and mumble, grow impatient” (31). The titles reveal some of the desire here, some of the Mormon holding-back and the human rushing-forward: “He’s Not Coming” (32), “Quick Tongue” (39), “Not Yet” (44).

The poems are tiny stories, pinpricks of images fixing meaning in moments. Mostly they’re not formal poems—I found only one rhyme, and it seemed accidental—but “Bioluminesce” (56), in Part III, is a fine variation on the sestina form as well as a heartful story where “talking through screens” has multiple resonances, multiple implications. Still, the free verse isn’t prosey, most of the time. Earley is a skilled poet whose work plays well with sounds, line length, and visuals. Individually and as a collection, these poems make a difference in the reader’s heart.

In Part III, the poems’ personae have married, lost a child, had another. “Our Bed Protests” (64) and “Upon Attending a Yoga Class With My Husband” (68) bring the collection full circle. The speaker, grown and happily attached, remembers what it’s like to be a child, feels herself a child again in the richness of young experience. Between these two poems is “Bobbing Fish,” where young parents have brought a balloon into the room of their sleeping child, who has been away briefly. They watch her quietly, relieved and reassured that all is well. And “when she sees/ us in the doorway, she says,/ ‘And what, may I ask, are you doing here?” They are “suddenly unsure of the answer/ until she sees the tail of the balloon/and chases it to the window…” (66)

This entire small collection is the tail of a warm, bright balloon. If we chase it to the window, we can understand our Mormon, human selves—wondering over, wishing for, welcoming the complicated experience that is mortality—that much better.