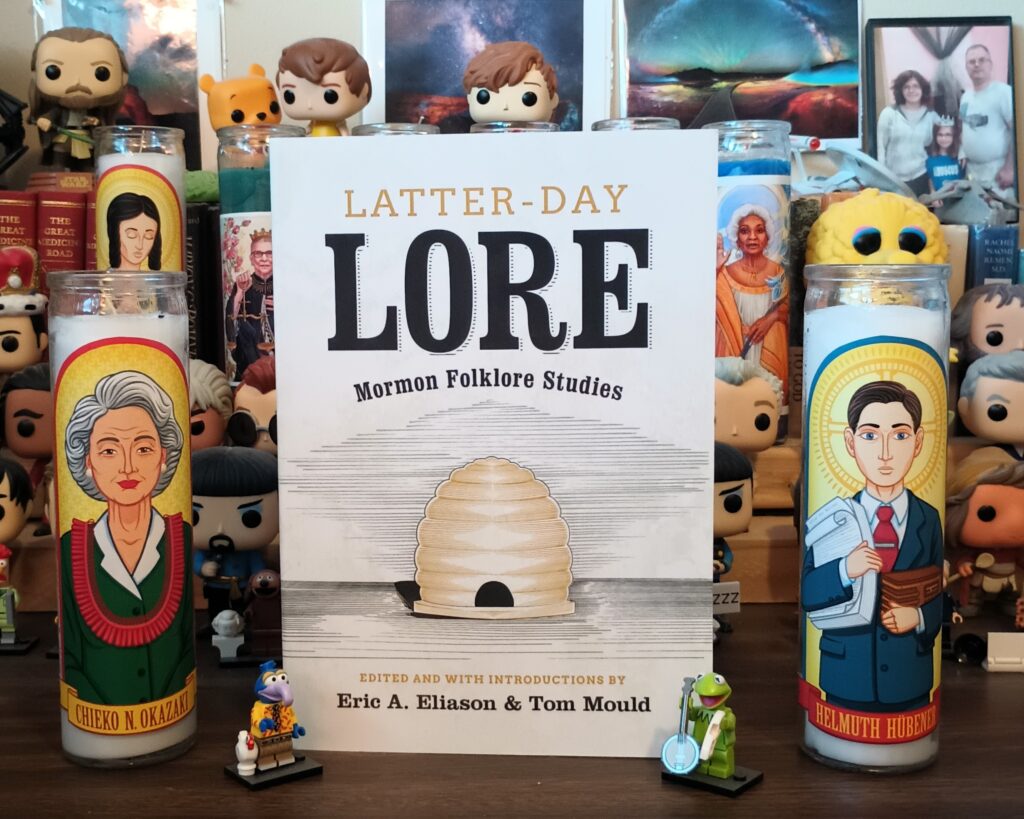

Title: Latter-Day Lore: Mormon Folklore Studies

Edited and with introductions by Eric A. Eliason and Tom Mould

Publisher: University of Utah Press

Genre: Religious Non-Fiction

Date: 2013

Pages: 591 (Notes etc begin on p. 483)

Binding: Softcover

ISBN: 978-1-60781-284-5

Cost (paperback): $34.95

Reviewed by Julie J. Nichols for the Association for Mormon Letters

“Folklore” is one of those words like “myth,” “belief,” and “ritual” whose associations, because they can’t be pinned down by numbers or proofs, tend to be eschewed by “rational” people. Those words, they say, do not name topics that can (or should) be studied academically; they can hardly be defined, let alone quantified. They’re illegitimate, the domain of fundamentalists. Witches. Masons.

But no. This book—Latter-Day Lore: Mormon Folklore Studies, first published in 2013 and containing essays themselves first published as long ago as 1942 with references to many even earlier scholarly articles and books, declares otherwise. Folklore, the editors assert, is what all of us (even the rich, the powerful, and the great) subscribe to when we eat traditional foods on holidays, recognize a regional architectural style, name our children with family monikers, and tell familiar jokes and stories. Folklore is a pattern handed down by repetition and recurrence. It marks a community as a community. If you participate in the folklore—the myths, the beliefs, the ritual practices—of a community, you belong.

And…it can be studied academically—has been, in departments of anthropology and literature, since the 1880s, when Franz Boas and other anthropologists “explored myths, legends, and rituals as one piece of culture, an approach that expanded the narrow view of ‘the folk’ as conceived by the literary folklorists” (11).

Mormon folklore has been a facet of folklore studies for decades. It was inevitable that eventually, Mormon folklore would be the subject of both insider and outsider investigation, originally in 1892 in a brief article by the Reverend David R. Utter describing the “superstition” of the Three Nephites, and then, more formally and broadly, in the 1960s by Richard M. Dorson, who was the first to identify Utah Mormons as one of five (later seven) uniquely American regional cultures. Latter-Day Lore is an overview and introduction to this rich and fascinating field, comprised of 28 essays and articles ranging in date of original publication from 1942 to 2013. This is not an analysis of recent developments but a compilation of seminal Mormon folklore studies and its practitioners: Austin, James, and Alta Fife on Momon life-landmarks (1948 and 1956); Barre Toelken (1959) on the Mountain Meadows Massacre; Gustive O. Larson on Porter Rockwell (1971); and many others.

(If there’s one complaint this lay reader might make about this well-conceived and well-edited volume, it is that the original dates of publication of the articles are not posted with the essays themselves. The essays are arranged thematically rather than chronologically. If you want to know when they were written—what era of folkway each essay illuminates as well as what topic–you have to reference the list of “Sources for Previously Published Chapters” on pp. 583-4. This is a flaw, in this reader’s opinion; only three of the chapters are published here for the first time, and it would be convenient and useful for any audience—instructor, student, or layperson–to see the date each essay was written right there in the text.)

Latter-Day Lore is divided into six sections. Each contains four or five essays discussing a major theme in Mormon folklore studies. Each is introduced by an impressive essay contextualizing the theme, mentioning many noteworthy scholars besides those whose essays are represented, and suggesting further areas of study.

Regional culture—landscape traditions, the beehive symbol, handmade hay derricks, and gravestones are among the topics treated in Part I, ranging from 1959 to 1989.

Formative customs and traditions such as creative dating invitations (Young, 2005) and marriage confirmation narratives (Schoemaker, 1989) are described in Part II.

“Magic”—narratives of interaction with the supernatural, with defensive or accepting responses to such narratives—is considered in Part III; pioneer stories in Part IV; humor in Part V (where the most recent essay comes from Ed Geary in 2013, but even the 2009 essay on BYU coed humor feels embarrassingly non-p.c. to me—I’d have liked to see some metacommentary on this and other time-bound investigations); and, in Part VI, approaches to Mormon lore from an international (i.e. missionary and global-church) viewpoint.

Every essay is rich with delicious examples of stories, practices, or symbols familiar to Mormons—not only identifying them but discussing their origins, the people who use them, and their significance to the communities in which they are or have been found. If you’re Mormon, you’re sure to find some aspect of your personal or cultural heritage in almost everyone. There’s a picture of my maternal grandparents’ Salt Lake City Cemetery gravestone illustrating the belief that “Families Are Forever” on p. 83. References abound to events, historical people and places, and agencies I’ve heard of or participated in all my life. Non-folklorists, then, are one happy audience of this book.

But watch out, because the scholarship of much that helps create your Mormon identity just might actually make a folklorist of you, an ardent student of every essay whether you originally thought you had an investment in it or not. Because the book comprises an overview of the scholarship; because it dives deep into 28 topics that (mostly) still resonate as markers of Mormon belonging, from retellings of Mormon history to missionary traditions to cultural assimilation in non-U.S. countries; and because it locates itself squarely in legitimate disciplines such as literature and anthropology (and others), you may feel stirrings to re-examine the stories and practices you take for granted—to join the other happy audience of Latter-day Lore, the teachers and students of folklore studies.

The quilt you sleep under, the name of your bank or your bakery, the in-jokes and familiar phrases you utter among Mormon friends and family may all be considered folklore, may all be up for grabs, not to be taken lightly but cherished, recorded, followed. Examined and understood as profound aspects of your identity, shared by your community and exhibiting qualities of folklore of every culture. Not to be taken for granted—not to be eschewed even (especially) by you, a rational reader—at all.