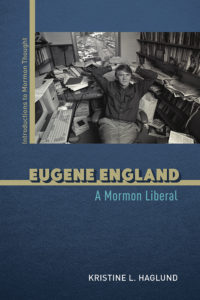

Title: Eugene England: A Mormon Liberal

Title: Eugene England: A Mormon Liberal

Author: Kristine L. Haglund

Publisher: University of Illinois Press

Genre: Biography, Mormon studies

Year Published: 2021

Number of Pages: 152

Reviewed by Michael Austin

Had Kristine Haglund managed to merely write a book about Eugene England–perhaps the most visible and influential Mormon intellectual of the last 50 years–it would have been an invaluable contribution to the burgeoning field of Mormon Studies. But the author has done much more than that. By setting England in conversation with the religious and intellectual spaces he inhabited, Haglund has created one of the most important guides we have to the development of Mormonism as an intellectual and cultural force in the 20th century.

The key to Haglund’s portrayal of England lies in the subtitle: A Mormon Liberal. In clarifying this term, she brings us a picture of the man. England was not, she argues, a theological liberal in the way that most Catholics and Protestants would understand the term. Nor can his liberalism be described as a position along the American political spectrum. Even the classical liberalism of Locke and Rousseau doesn’t quite fit when talking about Dr. England. To understand him, we must understand what a fundamentally Mormon variety of liberalism might look like.

As a Mormon liberal, Eugene England believed that Mormonism itself–its core doctrines and its spiritual tradition–created an ideal environment for what might be called a liberal approach to things like beauty, truth, and meaning. In such an approach, members of a spiritual community meet together, as spiritual equals, to create meaning together. The community values open dialogue, epistemic humility, and continual growth. England believed these things with all of his heart, and he increasingly found himself at odds with both a university and a corporate church that rejected them in favor of an illiberal and undemocratic model of authority and obedience. In this sense, Haglund argues, Eugene England was the last Mormon liberal–the final signpost for a path that Mormonism might have taken.

Haglund focuses her analysis of England’s life and work through this highly focused lens of a Mormon liberalism that is both fully Mormon and fully liberal. She analyzes his work as an essayist–one of the founders and early practitioners of a distinctively Mormon style of theologically infused, spiritually grounded personal essay. She explores his role as a co-founder of Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, which has been published continually for 55 years and remains the periodical of record of the intellectual and creative life of the Mormon people. And she examines his deep and lifelong commitment to a concept of atonement that brings people together and provides the opportunity for spiritual growth.

In the process of explaining Eugene England, Kristine Haglund also explains a lot about modern Mormonism as both the comprehensive spiritual tradition that he saw more clearly than anyone else of his time, and as the collection of correlated, bureaucratized institutional practices that he never saw quite clearly enough. This book is a rare gift to those who knew Eugene England and a perfect starting place for those who want to know him better.