Review

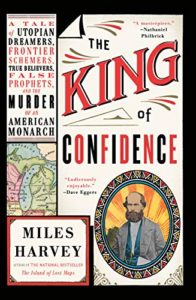

Title: The King of Confidence: A Tale of Utopian Dreamers, Frontier Schemers, True Believers, False Prophets, and the Murder of an American Monarch

Author: Miles Harvey

Publisher: Little, Brown and Company

Genre: History, biography

Year: 2020

Number of Pages: 401

Binding: Hardcover; also available as audio or ebook

ISBN13: 978-0-316-46359-1

Price: $29.00

Reviewed by Dennis Clark for the Association for Mormon Letters

Miles Harvey opens The King of Confidence with an angel watching Joseph Smith being killed, then flying to Wisconsin to herald James Jesse Strang as head of the Mormon church. If that sounds more like a novel than a history, you might not tolerate this book well. It is thoroughly documented, but it reads more like a fable than an academic history. Yet if you take a pass on this title, you will miss a fascinating tale of the rise and spread of the confidence man (the con man), particularly in the American Midwest.

For me, this has political resonance in our own time. And Harvey does make indirect, and sometimes direct, application of this figure in American civilization to the present day. My training in history is in literary history, and more specifically in American literature of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, with a side project in the study and writing of poetry. So when Harvey brings in the writing of Strang’s contemporaries, Herman Melville, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Walt Whitman among them, I find a resonance with my training, as well as with my religion.

Harvey asks about Joseph Smith’s life whether it was plausible (4-6) that he could have accomplished all he did before that assassination. He answered, “No, none of it is the least bit plausible. But in the antebellum era … plausibility was about as fashionable as a three-cornered hats” (6). I left out of that quote a wordy definition of antebellum; that Harvey inserts it tells me a lot about how he views his audience.

After multitudinous chapters disclosing Strang’s early life in western New York and his career as a prophet and as a king, Harvey concludes in his epilogue with what is perhaps the most direct reference to Strang in the literary canon. The reference is found in Melville’s The Confidence Man: His Masquerade. In this novel, the title character appears aboard a Mississippi river-boat without purse or scrip and proceeds to fleece many of the other characters of the contents of one or the other. At one point, he offers to sell one of the younger victims some stock in “the New Jerusalem.” “New Jerusalem?” the prospect asks. “Yes, the new and thriving city, so called, in northern Minnesota. It was originally founded by certain fugitive Mormons. Hence the name.” The confidence man then produces a map of the townsite and shows the planned locations of all the amenities[1].

Some critics Harvey consulted argue that the reference may be to Joseph Smith and Nauvoo, or even to Brigham Young and Salt Lake City. Harvey instead cites an article by Richard Dilworth Rust, appearing in BYU Studies in 1999, which argues that the reference may not be to Joseph Smith but to Strang (297). However, that may be, the two scenes, the flight of the angel and the approach of the con man, bookend this history. And as I said, Harvey’s documentation is overwhelming.

Yet Harvey’s is a somewhat scattershot and superficial application of all that research. For instance, Harvey appears not to have read The Book of Mormon. In only one instance in which Harvey quotes it does he cite the Book of Mormon itself. This is when he discusses the curse of “a skin of blackness” which Nephi claims had marked the Lamanites (2 Nephi 5:21), and he uses the quote to talk about Brigham Young’s policy of excluding Blacks from the priesthood, and Joseph Smith’s evolved views of Blacks. Had he read the book, he could not write a sentence like “The Book of Mormon, after all, tells the story of a righteous people, the Nephites, who are exterminated by their rivals, leaving behind the Book of Mormon to be discovered by Joseph Smith” (144-145). Anyone who had read as far as 1 Nephi 13 would realize that Nephi knew, from a vision, “that the seed of my brethren did contend against my seed, according to the word of the angel; and because of the pride of my seed, and the temptations of the devil, I beheld that the seed of my brethren did overpower the people of my seed” (1 Nephi 12:19). This in a vision in which Nephi sees the future of both branches of those whom he considered his people.

Moreover, Harvey ignores, if he even read it, the conditionality of this curse: the next verse, 2 Nephi 5:22, reads “And thus saith the Lord God, I will cause that they shall be loathsome unto thy people, save they shall repent of their iniquities.” The Lord God continues: “And cursed shall be the seed of him that mixeth with their seed, for they shall be cursed even with the same cursing. And the Lord spake it, and it was done” (verse 23). The whole matter of this “skin of blackness” has caused no end of discussion amongst Mormons, but one thing is clear from the text itself: it refers to the Lamanites when they are unrighteous, not to Blacks of African descent. And it is in the latter context that Harvey deploys it.

I wouldn’t dwell at such length on what is a fairly minor point in Harvey’s narrative, except that, from what I can tell, he treats a fair number of his sources this way, proof-texting his way through antebellum American life and literature. But, to be fair to Harvey, he is not set on explaining anything having to do with the Mormons who followed Brigham Young, or those of the Reorganization, except that those who follow James Jesse Strang are almost always referred to in the contemporary newspapers and narratives he quotes as “Mormons.” That’s the context in which Strang founded his movement. And that’s Melville’s usage as well.

Moreover, in King of Confidence, that quote about “a righteous people, the Nephites” is offered in evaluating a stage performance of the play Pizarro in Peru; or, The Death of Rolla by Richard Brinsley Sheridan, presented in Nauvoo. The performance of which, according to Helen Mar Whitney, moved “nearly the whole audience,” including Joseph Smith, to tears. Harvey speculates that “[t]he reactions in Nauvoo may have been so intense because Mormon audiences seemed to recognize something of their own story in the play. The Book of Mormon, after all, tells the story of a righteous people, the Nephites, who are exterminated by their rivals, leaving behind the Book of Mormon to be discovered by Joseph Smith” (144-145). When I tried to check the source of that audience reaction, there was no entry in the relatively comprehensive bibliography for Whitney, and no entry in the index. I found the source in a previous note keyed to page 141, attributed to “one young actress who had shared the stage” with George Adams, a tragedian, and henchman of Strang. I leave it to you to follow that strand through the book, but my point is that it may have been Whitney, one of Joseph Smith’s youngest plural wives, who “performed in Pizarro with Adams … when she was fifteen.” Harvey does not say that this was the performance in Nauvoo, which he says occurred “in April of 1844, two months before the murder of Joseph Smith,” so if it were, she would have been gauging audience reaction from the stage or reporting what others told her. Whitney’s recollection was published as “‘Scenes and Incidents in Nauvoo’ Woman’s Exponent, vol. 11, no. 12 (November 15, 1882)” (343-344), 38 years later, when she was 53.

It may seem to you that I am picking nits. What I am trying to do is forewarn you, as I said at the outset, that this is no straight historical narrative; it follows the pattern set by Laurence Sterne in The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman. It follows a twisting, circuitous path through the antebellum United States partly because Strang followed such a path through the states himself. It follows that path because Strang, and the people whom he gathered about him, and those who attached themselves to him seeing and seeking advantage, is emblematic of all the forces that were at play in the lifetime of Joseph Smith. I repeat, if you want an entertaining jaunt through that epoch, read this book.

[1] In Library of America #24, containing, among other titles, The Confidence Man: His Masquerade; the scene quoted occurs in Chapter 9 of The Confidence Man, page 893