Review

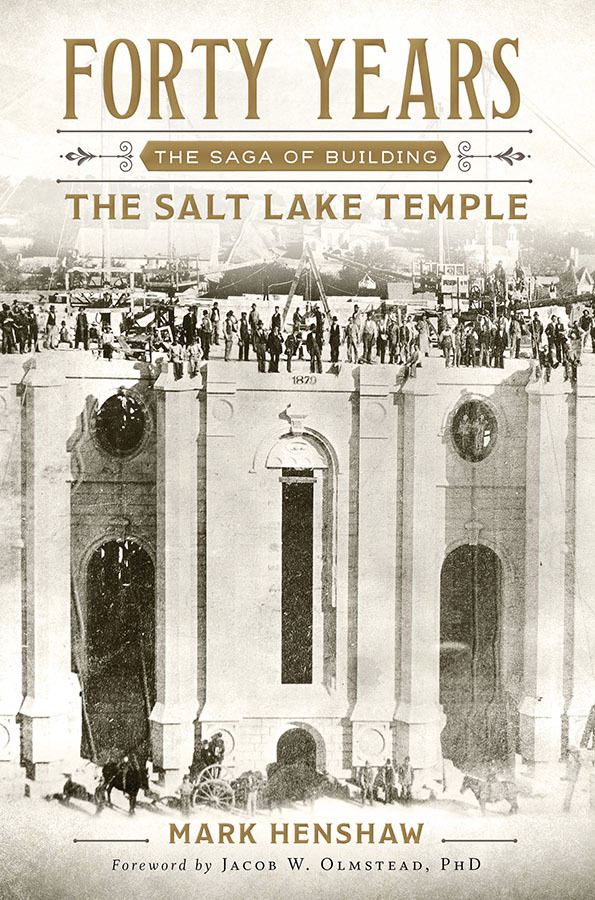

Title: Forty Years: The Saga of Building the Salt Lake Temple

Author: Mark Henshaw

Publisher: Deseret Book

Genre: History

Year Published: 2020

Number of pages: xvi, 543

Binding: Hardcover

ISBN13: 978-1-62972-750-9

Price: $34.99

Reviewed by Dennis Clark for the Association for Mormon Letters

Jacob W. Olmstead, in his foreword to Forty Years: The Saga of Building the Salt Lake Temple, poses the question many of you might ask if you saw this book in the store. He says you might ask yourself “why you are reading a foreword by somebody you’ve never heard of” (ix). Author Mark Henshaw adds to the perplexed reader’s mystification in his preface when he writes, “The Church does not lack for resources to build or maintain” temples (xiii). So, what is so gaga about this saga?

That’s what Olmstead explains. He’s “a historian who works for the Church History Department of the Church … in Salt Lake City”, tasked with researching “the construction of the Salt Lake Temple” (ix). He says “I spent thousands of hours going through the vast holdings of the Church History Library” for this task, so when he learned of Henshaw’s work, “[a]s I read his manuscript, I was delighted to learn that he had written the kind of book I felt should be written for the temple — and, more important, what the temple deserved” (ix-x).

I was interested in Forty Years because of some family lore. My mother’s mother was born to Welsh immigrants on both sides of her line, and her grandfather, John Heber Lloyd, was said to have been the person who applied the gold leaf to the statue of Moroni on the temple. I wondered whether the book would mention him. As I plunged into reading, I noted that Henshaw relies heavily on primary sources, mostly in the Church History Library. So as read, I hoped to find a mention of John Heber Lloyd in those primary sources. Having worked in that library as a librarian for two years, from December 1976 into January 1979, I found Henshaw’s documentation not only thorough but amazing. When I worked there, the predominant mood amongst those supervising Leonard Arrington was suspicion and reticence — many of the older employees were collecting anti-Mormon items to condemn the authors during the millennium, and had classified Arrington’s Great Basin kingdom as anti-Mormon. After Arrington was shunted aside, into the Joseph Fielding Smith Institute for Church History, the Historical Department became very hard to work with.

That changed before the advent of the Joseph Smith Papers Project, and Henshaw has benefited from the new mood and openness. Not only that, but this book benefits from many articles and volumes published since the thaw, and from direct access to various sources, and online access to others, like the entirety of Wilford Woodruff’s journals. In point of fact, what Henshaw has produced is a history of the Church in the Salt Lake valley, centered on the saga of the temple, and enriched by many digressions into the history of the relations of the Church with the nation at large. And with the natives being displaced by the Mormon immigrants.

To his credit, Henshaw recognizes that the Indians were here before the Mormons. And he tells an interesting story about relations between the two groups in 1853, which I will quote at length:

The Timpanogo were a group of Shoshone led by a chief named Walkara, or Walker, as the Saints called him. He was, first and foremost, a notorious horse thief. That was hardly unknown in the West … but Walkara’s reputation for thievery was notorious even among the tribes. He was a duplicitous man, acting friendly toward the white settlers one day and ugly the next. When the Saints had first entered the valley, a council of braves had met to determine how to treat the newcomers. Walkara had argued for a massacre. The younger braves sided with him, the older braves and chiefs with a leader named Soweite, who had argued that perhaps the Saints, like the Utes, had been driven to the mountains for refuge. The council had split, and only when Soweite had flogged Walkara with a whip did the council choose the peaceful route (91-92).

It’s a really interesting story to me since I grew up in Provo and attended kindergarten in a school named for Sowiete. But, as far as I can tell, Henshaw gives no source for it. He cites only a speech by Brigham Young from The Journal of Discourses 1:106 in connection with the tale, in which Brigham repeats that he doesn’t trust Walkara, or anyone else, blindly[1].

Walkara was then discovered to be a slave trader, selling native children to Mexican agents. What unfolds from that discovery is a war between Mormons and Walkara’s group, including an incident leading to the murder of John W. Gunnison and seven others of his surveying party near Sevier Lake (94), after which Walkara and Ka-no-she, a chief of the Corn Creek tribe from which Gunnison’s killers came, “helped restore the peace,” although Walkara continued his “depredations” for seven more months (94). That’s why the story is in the book: Brigham Young was governor of Utah territory, and such matters were impediments to the work on the temple, which had begun in February 1853, with the laying of the cornerstone on 6 April 1853. Both his attention and the labor of the Mormons were interrupted by many seemingly irrelevant events, and Henshaw wants to chronicle them all, to produce a faithful record.

I really enjoyed reading Forty Years, although it took me forty days because I kept getting interrupted. I kept checking the end-notes to see where some stories came from, and most of those from Mormon writers were from primary sources, but most of those setting the labor on the temple in the larger national context are from secondary sources. Henshaw is particularly good in discussing the relations between Mormons and the national government, and the effects of the Utah War on the temple, but says nothing, for example, about the Mountain Meadows Massacre or the effects of ongoing investigations, especially after the Civil War, into that incident.

Henshaw’s most effective chapters on impediments to the construction relate the problems the Church had with the Federal government enforcing the anti-polygamy laws that passed starting with the ascendancy of the Republican Party and the election of Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln’s primary interest in Utah Territory was to keep it on the side of the Union, so he didn’t bother to enforce the anti-polygamy laws passed by his fellow Republicans. In fact, Lincoln’s Secretary of State, William H. Seward, asked an office-seeker from Missouri, Orion Clemens, to stop in Salt Lake City and sound out the Mormon leaders on their attitude towards the Union. Clemens’ younger brother, Sam, was traveling with him and had in fact financed the trip, for Orion had been awarded the office of Secretary of the Nevada territory. Sam had been a pilot on Mississippi riverboats and wanted to get out of St. Louis because both the Union and the Confederacy were trying to conscript every pilot they could, so he lit out for the territories. He recounts his adventures in Salt Lake City in Roughing it.

How Henshaw missed that story I don’t know, because he covers every president from Martin Van Buren through William McKinley, and their relations with the Latter-day Saints, in great detail, discussing the building of every temple and attempted temple through the finishing of the one in Salt Lake City. And it was the Republican presidents who pressed most strongly on the Church, including escheating — confiscating — the property of the Church, imprisoning men convicted of cohabitation, and allowing the territorial governor’s signing of a bill enfranchising the women of Utah Territory in the hopes that they would outvote the men and outlaw polygamy. That was in 1870. Later, Republicans in Congress passed laws in effect disenfranchising all Mormons by taking the vote from anyone who even believed in a religious right to practice polygamy. While this was perhaps the first attempt by the GOP to disenfranchise a significant portion of a state’s electorate, it would not be the last.

Through all this harassment, the stonecutters and masons continued to work on the temple, even while federal marshals and lawyers were attempting to seize Temple Square. The laws did allow the Church to keep buildings with a solely religious purpose, but all property of a value over $50,000 was to be escheated to the federal government, and by then the Tabernacle, the Assembly Hall, and the Temple were each worth more than that. By 1890 the Church was essentially insolvent, although members and units in whose hands the Church had entrusted its assets could still support the work, those persons were scattered throughout the Territory and surrounding states, and they dared not send any assets through the tithing office because it, too, was under government surveillance.

Even under these conditions, the work continued. The capstone was laid on the temple on April 6, 1893, forty years to the day after the cornerstone was laid, which marked the completion of the exterior of the temple. And the statue of the trumpeting angel was lowered into place on the capstone later that day. But, I learned, much to my disappointment, that the statue was “cast in copper” by W. H. Mullins and Company in Salem, Ohio, and then “covered in polished 22-karat gold” and shipped back to Salt Lake City to await the ceremony (412). As nearly as I can tell, John Heber Lloyd did not begin work at the temple until it was being finished. By then he was 35, had been trained as an artist and a “grainer” — one who simulated hardwood grain on inferior woods, or grain on plaster to simulate granite — and worked as an artist in fine homes all over Salt Lake City, according to his son. So, after the capstone was laid and Cyrus Dallin’s statue of Moroni lowered in place atop it, the Church’s leaders decided to finish the interior in one year, and dedicate the temple, while Wilford Woodruff was still alive. That was when extensive work on the interior began, still without much money and without final plans for the interior, and all that was worked out as the work progressed.

It would have been in that year that John Heber Lloyd worked as a gilder in the temple. I trust the family stories about him coming home with streaks of gold in his hair because he had to run his stylus through his hair to put a static charge on the metal tip so he could pick up the gold leaf and affix it to the surfaces he was working on. That final year was brutal for both the workmen and the architects and involved everyone in long, long hours and six-day work-weeks, and I would venture to say that there are many families like mine with similar stories of long hours worked to finish the temple, but it was dedicated on April 6th, 1894, by Wilford Woodruff. According to the Deseret News, a monstrous, demonic windstorm began on the morning of the dedication, rising to howling heights, toppling chimneys and stripping shingles and ripping off roofs and in general wreaking havoc in the City, and audible in the upper room of the Temple, where the dedication ceremony was held. The wind died as Lorenzo Snow offered the benediction, at about 12:30 (453-458).

I trust that story about Lloyd and the gold in his hair because nothing Henshaw says contradicts it. But the legend about this great-grandfather of mine was perpetuated in a newspaper story printed thirty years after Moroni was set in stone in 1894, which would make it 1924. The story repeats the tale of the “historic high east wind” but also intimates that “young John Lloyd” gilded Moroni and would do so again. One interesting detail the newspaper repeats leaves a slight hope for the family legend: “The wind twisted Moroni’s gold[en] trumpet, and it took an expert, n[ot] only in steeplejacking, but in hor[n] straightening, to remedy the situ[a]tion. … The man who straightened Moroni’s trumpet long ago was Evan Arthur of Salt Lake, who is leaving tomorrow on a mission for the church to Wales.” And who knows? Maybe that straightened trumpet needed a little touch-up to its golden coat? And maybe that straightening is what led the trumpet to break off in the recent quake? Henshaw is silent on both points, but I trust that the next edition of his magnum opus will take up the matter.

[1] When I submitted this review, the editor, Andrew Hamilton, thought this story sounded familiar, and found it repeated and discredited in both Will Bagley’s Whites Want Everything and Jared Farmer’s On Zion’s Mount: Mormons, Indians, and the American Landscape. This justified my skepticism and verified my opinion. Hamilton adds: “Apparently, the source for the story is an 1885 history of Provo and Spanish Fork by Edward Tullidge. Tullidge provided no sources for the story and by then everyone involved was dead.” Any reader wanting to investigate this story further should check out Bagley’s and Farmer’s books. This should not stop you from reading Forty Years, just make you a bit skeptical of too good a story.