Review

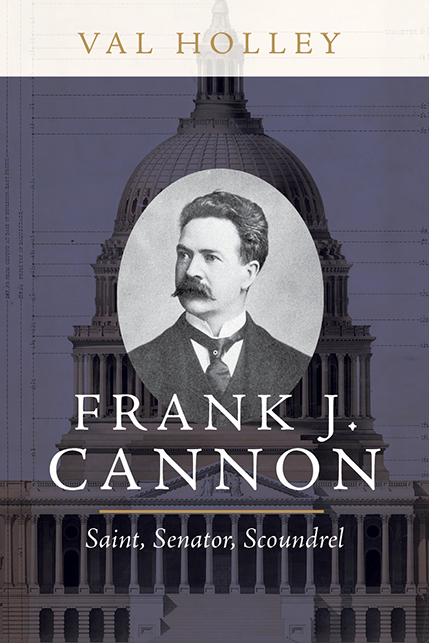

Title: Frank J. Cannon: Saint, Senator, Scoundrel

Author: Val Holley

Publisher: University of Utah Press

Genre: Biography

Year Published: 2020

Number of Pages: 369

Binding: Paper

ISBN 13: Cloth, 9781647690120; Paper 9781647690137

Price: Cloth, 60.00; Paper, 29.95 eBook, 32.00

Reviewed by Melvin C. Johnson for the Association of Mormon Letters

Frank J. Cannon: Saint, Senator, Scoundrel by Val Holley (University of Utah Press, 2020) does an admirable job of telling his biography, even if not a complete one. Frank Jenne Cannon (1859-1933), one of the many sons of George Q. Cannon, may be the most important Utahn in history that most Utahns do not know. He was not a General Authority like his half-brothers, Abraham H., Sylvester Q., and John Q. Cannon. He was, however, one of the fathers of Ogden’s growth to prominence, an editor of several newspapers, an emissary of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormon) leaderships in Salt Lake City to the powerful in Washington, D.C., one of the godfathers of brokering a deal between powers ecclesiastical and political that made Utah a state; and the first United States Senator from Utah (1896-1899). He was also a sinner, a Saint, a scoundrel, a womanizer, a functioning alcoholic, and much more.

Cannon was a speaker extempore who would overflow venues in America and Europe on his name alone. At first, he defended the Church. The ghostwritten The Life of Joseph Smith just one example[1]. He later the Church as well. One example being in Under the Prophet in Utah, a scathing expose of Brigham Young’s cunning ascendancy in the Mountain West[2]. One always knew where Frank Cannon stood. Cannon lambasted Republican Senator Reed Smoot, LDS Church President Joseph F. Smith, and Apostle Heber J. Grant: Smoot for his conservative Republicanism, and Smith and Grant for protecting and denying the continuation of polygamy after the Manifestos of 1890 and 1904.

Cannon was one of many sons born to George Q. Cannon and Sarah Jenne Cannon, a plural wife. From 1880 to his death in 1901, George Q. was arguably the second most important Mormon in the Church. Frank’s marriages to sisters Martha Brown and May Brown were sequential, not polygamous, marrying May the year after Martha died. No documents or reminisces remain that illuminate the personal landscape of these romances. Within twelve months of marrying Martha, he sired a child in faithlessness, which his wife forgave him for, and the child was adopted into a relative’s family circle. Frank and May’s marriage lasted for thirty years until her death. He abused alcohol for decades, which sent his brothers often prowling for him in the red-light districts of Ogden and Salt Lake City.

Yet Frank was a lifelong foe of polygamy; his opposition was not necessarily moral or ethical but rooted in his absolute belief that eliminating the practice would make Utah’s statehood far more likely. He served as Territorial Delegate to Congress and U. S. Senator from 1896-1899. His subterranean struggle with his father for the senatorial seat only enlivens the story. Surprisingly, the death of his father in 1901 fortified Frank’s devotion as a guardian of the LDS church. That did not last long. The death of his father was followed seven months later with the rise of Joseph F. Smith to President of the LDS church pushed Frank into apostasy. His opposition also to Senator/Apostle Reed Smoot as well as Apostle Heber J. Grant only quickened his exit as the LDS leadership rallied to secretly continuing the practice of polygamy. Cannon’s sharp, vindictive editorials against Smith and the LDS Church and polygamy during his brief time at the helm of the opposition Salt Lake Tribune caused his public ejection from the Church.

Holley writes well, and I try to give an example of an author’s prose in my reviews. One example by Holley discusses the irony, as exemplified above, that ruled Frank J.’s life:

Frank Cannon’s entire life was premised on ironies. While the Edmunds Act brought untold grief to the Mormon people, the fraught environment in Utah was essential to Frank’s rise. He anticipated that the lodestone of Utah statehood, once attained, would convey “the highest dignity of human privilege.” Yet statehood, which ended Utah’s estrangement from the nation, marked the beginning of Frank’s alienation – despite his being a U.S, senator – from the Mormon Church. His later public career and popularity in Denver, Colorado, demonstrate the advantages he might have given Utah if it had permitted him to rise in Senate seniority. (6)

Yet another example of Holley’s excellent writing is his ability in demonstrating the ironies and contrasts and confusions not only of Frank J.’s life is that those characteristics extended beyond him to that of his antagonists in the Church’s leadership. One instance is the attempt to sell church bonds in the eastern United States in 1898 to stave on the Church’s financial disaster. Holley writes that:

[Joseph F.] Smith, [once a supporter of Frank J] on the other hand, libeled Frank, in his authorized biography, Life of Joseph Smith. Recalling the 1898 effort to sell church bonds to eastern capitalists, Smith told the biographer – his son – that Frank “was to receive a very handsome commission” until Smith “prevented him from dipping his hands into the Treasury of the Church.” George Q.’s journal, however, noted that Frank refused a commission. Smith blamed Frank for convincing the leadership that the bonds must be sold in the east instead of Utah. According to George Q., however, Smith “was very emphatic” on selling the bonds in the east, uniting the First Presidency to overrule the apostles, who favored Utah. Smith even made a motion to authorize Frank to go ahead with the negotiations in the east. (259)

Frank J.’s final years, although not as exciting as his days in Utah, were spent in traveling the states and Europe on behalf of his broad commercial projects. His economic beliefs had cost him his political career in Utah. It was Cannon’s vote in the Senate for a tariff that would have hurt Utah’s sugar economy that ended his electoral run in 1899. A long-time Republican, the doctrine of Silver and bimetallism eventually led him into the Democratic Party. He never let go of his commitment to bimetallism in general and silver in particular. In his last twenty years, he still had the ear of presidents and Congress about his enduring belief in silver. He still could fill lecture halls. In his final days before his death, he was lobbying for a tremendous infusion of silver to modernize and rejuvenate the Chinese economy into one of the world’s dominant manufacturing countries.

A final irony of his life, despite his roles in Utah statehood and despite his continual fight against polygamy and despite his fame over the decades nationally and internationally, the newspaper death notices in Salt Lake City were far and few between.

I have one solid concern about this work. Holley fails to describe in-depth the ‘why’ of the underpinnings of Cannon’s alcoholism and infidelity. One needs not a Fawn Brodie psycho-history treatment, for some it of must be rooted obviously in the authoritarian character of his domineering father. A rip-roaring compulsion for excessive amounts of alcohol and forbidden sex during the first twenty or more years of his adult life indicates the enormity of Cannon’s addictive nature. But was it also subterranean resistance to the rigid requirements and mores of Mormonism? I wanted Holley to deal with this issue in more detail and was denied. Holley, unfortunately, fails to get to the interior of Cannon’s personality.

Frank J. Cannon deserves this well-written, extensive, and excessively documented biography. The hell-bent scion of arguably the second-most powerful man in the church deserves his place in the canon of good Mormon history. The work is timely and worthy, and well worth the reading. I recommend to all Mormon Studies scholars and interested laypersons to examine this amazing personality that so influenced political Mormonism in the American West. This achieves what President Douglas Alder of Dixie State University once told me about another writing: “this is an important book.”

[1] The Life of Joseph Smith was attributed to George Q. Cannon and published in 1886 by George Q. Cannon & Sons (Later Deseret News Press, then Deseret Book).

[2] Published in 1911