Review

Review

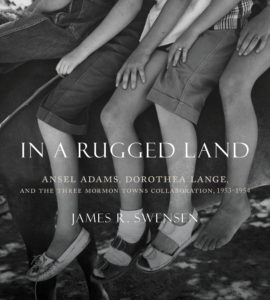

Title: In a Rugged Land: Ansel Adams, Dorothea Lange, and the Three Mormon Towns Collaboration, 1953-1954

Author: James Swensen

Publisher: University of Utah Press

Genre: Documentary Photography, History

Year Published: 2018

Number of Pages: 340

Binding: Paper, Ebook Available

ISBN: Paperback 9781607816287, eBook 9781607816294

Price: Paperback $ 34.95, eBook $ 28.00

Reviewed by Andrew Hamilton for the Association for Mormon Letters

In 1953 and 1954 famed photographers and old friends Ansel Adams and Dorothea Lange toured the Mormon towns of Gunlock, Toquerville, and St. George photographing the people, places, and surroundings for an article that would appear in the 6 September 1954 edition of Life magazine. This was to be an important project for both artists. In 1953 it had been years since Dorothea Lange had been involved in any major projects due to poor health. Meanwhile, “Ansel Adams was in the middle of a mid-career low” and was struggling both “emotionally and professionally” and desired to try some new work that would be more “artistically satisfying” (see pp. 19-22). The “Mormon Towns” project was meant to satisfy the needs of both artists and document Mormon life for a curious country.

James R Swenson’s book, In a Rugged Land: Ansel Adams, Dorothea Lange, and the Three Mormon Towns Collaboration, 1953-1954, published by the University of Utah in 2018 takes these 65-year-old, nearly forgotten photographs from two of America’s master artists and presents them to a new generation. Rugged Land is divided into ten chapters that present a mix of Utah and Mormon history, biographical information on Lange and Adams, a history and interpretation of the project and, of course, the photographs.

The first three chapters give some history and background on Lange and Adams and why they chose to do the project; one chapter each is then dedicated to the work in each town. The final chapters discuss an unfortunate rift that occurred between the artists, the layout of the project, the publication of the story and its aftermath (unfortunately some of the Mormon subjects were very upset and the possibility of lawsuits was even brought up), and some final words, observations, and interpretations by Swenson.

I’m going to be completely honest. I purchased this book for the photos. I wasn’t even thinking about or aware of what was in the text when I bought it, so it was a complete bonus for me that Swenson’s text is AMAZING. The story behind the “Mormon Towns” project is fascinating. Lange and Adams came together as old friends to do a wonderful collaborative project and boost both of their careers in times of personal trial. Unfortunately, artistic differences, disagreements with Life, and some hurt feelings among the subjects caused the whole thing to blow up on them. Swenson explains the whole story in excellent and sympathetic detail.

Swenson’s text also provides wonderful history and a very interesting anthropological study of mid-twentieth-century small-town Mormonism. As a sample, writing of Adams and Lange’s arrival in Gunlock, Utah, Swenson states that while they arrived with “connections and secured permissions” they were also met with “suspicion” and skepticism (p.84). They were told by the locals that, if they wished to succeed in gaining access to the town and its people, they must “do it through the bishopric.” They first went to Bishop Ivan “Tobe” Holt Hunt (p. 84). Before deciding if he would give the word that would allow the photographers to go ahead with their work, Bishop Hunt contacted Juanita Brooks for advice. “Salt Lake City” (ie, the LDS General Authorities) were also consulted. Adding to the concerns and suspicions of the local Mormons was that Lange and Adams showed up shortly after the government raided the polygamist town of Short Creek. While the two communities were theologically divided, their “small town values” were nearly identical, thus leading the citizens of Gunlock to worry about what the photographers’ true motives were. As I read, my reaction was “That’s SO Mormon.” I encourage you to read the story. It’s an amazing study of small, midwestern town behavior, absolutely fascinating.

One of the things that I LOVED about this book was that the presentation of Adams’ and Lange’s stunning work proved to me that “photography” is something of a lost or dying art. In our time almost EVERYONE carries a camera EVERYWHERE. We take snaps of EVERYTHING. Your kid does something cute: click, click, click, click. A cool cloud floats by: snap, snap, snap, snap. Something mildly amusing happens: tap, tap, tap, tap, on the button on our phones and within seconds we upload it onto Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat, or maybe group text it off to our families. We live in a world saturated in pictures. I am not complaining; I am glad that we have the ability to preserve and share special moments. But this book is a great example that there was a time when taking a photograph was an artistic endeavor. Masters like Adams and Lange chose their cameras, lenses, and film stocks carefully. Angle, lighting, shading, focal length, focus and so many other small details were weighed and considered with great care. Much thought and work were required before the shutter was finally clicked. The work, artistry, and mastery of craft show in each and every photograph in this book.

I could honestly go through an entire dictionary and thesaurus to describe the photos in this book: beautiful, stunning, masterful, awesome, fantastic, emotive, sacred, and that is just a start. I’m not ashamed to write that I got a little emotional looking at the photos in this book. I have spent most of my life in mid to small sized towns in Utah and Idaho. Many of my forebears lived out their lives in small, Mormon, central Utah towns. These are my people. But even if you don’t have the personal connection, I think that you will connect with the photos in this book because Lange’s and Adams’ subjects and photos evoke an “everyman”/“everywoman” quality. The photos in this book will recall summer picnics, trips to grandma’s house, family outings, childhood fun, and time spent with loved ones. All of the work is beautiful, but I want to quickly highlight four images that particularly affected me.

Bread holds a place of important symbolism in American, Christian, and Mormon life. We eat it, we share it, we throw it at birds, it is a symbol of unity, it is used in Christian/Mormon covenant making, it is a major part of our lives. If I need some bread, I run to the local market and for about a dollar I can have a sliced-up loaf of Wonder, or maybe if I feel fancy, a loaf of “French Bread” from the store’s bakery department. But much like the lost art of taking a photograph, there was a time where making enough bread for a family was an all-day affair in many women’s lives. For these reasons I absolutely love the photo “Loaves of Bread, Utah, 1953”[1]. The photo is beautiful. The framing, lighting, and use of shadow and shading are masterful. To me this is a sacred image. It may just be an image of food but to me it says so much about women, family, small town life, and religious experience.

I have similar feelings about the image “A Winter’s Provender [Jessie Waite Hunt], Gunlock, Utah, 1953”[2]. This close up of a woman holding four home bottled jars of beans says a lot to me. I fully realize that there was a time when home bottling and canning were common. Many people, at least in the small towns that I have lived in, still “can” a portion of their harvest in the fall. But Mormons in particular have turned “canning” not only into an art form but into something of a tenet of their faith. It is often a source of pride for the bottler, much like Aunt Bea’s homemade pickles. When I look at this image I don’t just see hands holding beans: I see hard work, hours spent, sweat and perspiration, tilling, hoeing, weeding, watering, picking, washing, cutting, flavoring, boiling, sealing, and sharing. But mostly I see love.

A very touching, non-food image is “Riley Savage with his Grand Daughter, Leeds, 1953”[3]. The photo features 84-year-old Riley Savage sitting on his porch showing a book of family photographs to his granddaughter. I’ll quote Swenson who writes, “There is a charm of closeness in this image, as the elderly grandparent passes on names and faces to his young descendant in overalls. A necessary process in a Mormon world where family history is sacrosanct” (p. 137). Having shared many such moments with parents and grandparents as they have shared photos and stories of family and ancestors, I just love this image.

I love the last photograph that I want to mention for an entirely different reason than the first three. Found on page 199, the photograph is called “Young Woman, St George, Utah, 1953”[4] It is a closeup of a young woman in a what appears to be a dress wearing a medallion. She is smiling for the camera. It is SO utterly timeless. It is over 60 years old and was taken exactly 20 years before I was born but it could have been taken yesterday. It could be any of my daughters. I love it because it reminds me that “the past” is not all that different from the now. We are all so intimately connected. Of it Swenson said, “In one of the most remarkable images of the project Lange and Adams photographed a young girl whose eyes exude and the beauty of the Saints … Her experiences in St. George allowed Lange to ponder the nature of life. ‘Descendants become Ancestors, and ancestors become a memory,’ she wrote: ‘Many things change, and some endure. Many are gained, and some are lost. It is not time that moves, but life” (p. 199).

That quote from Lange is a perfect summary of why I love this book so much. It gives the reader a complete “circle of life … moves us all … despair and hope … faith and love”[5] type vibe. This book is spectacular. The images are moving and poignant. After reading James Swenson’s text and savoring the masterful artistry of Ansel Adams and Dorothea Lange as found in “In a Rugged Land,” I have come to believe, and think that fellow readers will agree with me that Paul Simon was right when he sang “Everything looks better in Black and White”[6]

[1] Page unnumbered but would be xiv, labeled “Figure 0.5

[2] p. 104, Figure 4.23. Bottling is featured in several photographs in this chapter.

[3] p. 136, Figure 5.28. Leeds is near Toquerville

[4] Figure 6.58

[5] John, Elton and Rice, Tim. “The Circle of Life.” The Lion King Soundtrack, Walt Disney, 1994.

[6] Simon, Paul. “Kodachrome.” There Goes Rhymin’ Simon, Columbia Records, 1973. – I am fully aware that in the studio recording on the original album Simon sings “Everything looks WORSE in Black and White”, however, in many live performances he sings it as I have quoted using the word “Better”. The most notable of these performances is the 1981 “Concert In Central Park” reunion performance with Art Garfunkel. In an interview about Kodachrome Simon said “I can’t remember which way I originally wrote it – ‘better’ or ‘worse’ – but I always change it” (“Still Creative After All These Years,” interview with Daniel J. Levitin, Grammy magazine, Winter, 1997).