Review

Title: The Darkest Abyss

Author: William Morris

Publisher: BCC Press

Genre: Fiction/Short Story Collection

Year Published: 2022

Number of Pages: 226

Binding: Paper

ISBN: 13: 978-1948218689

Price: 9.95

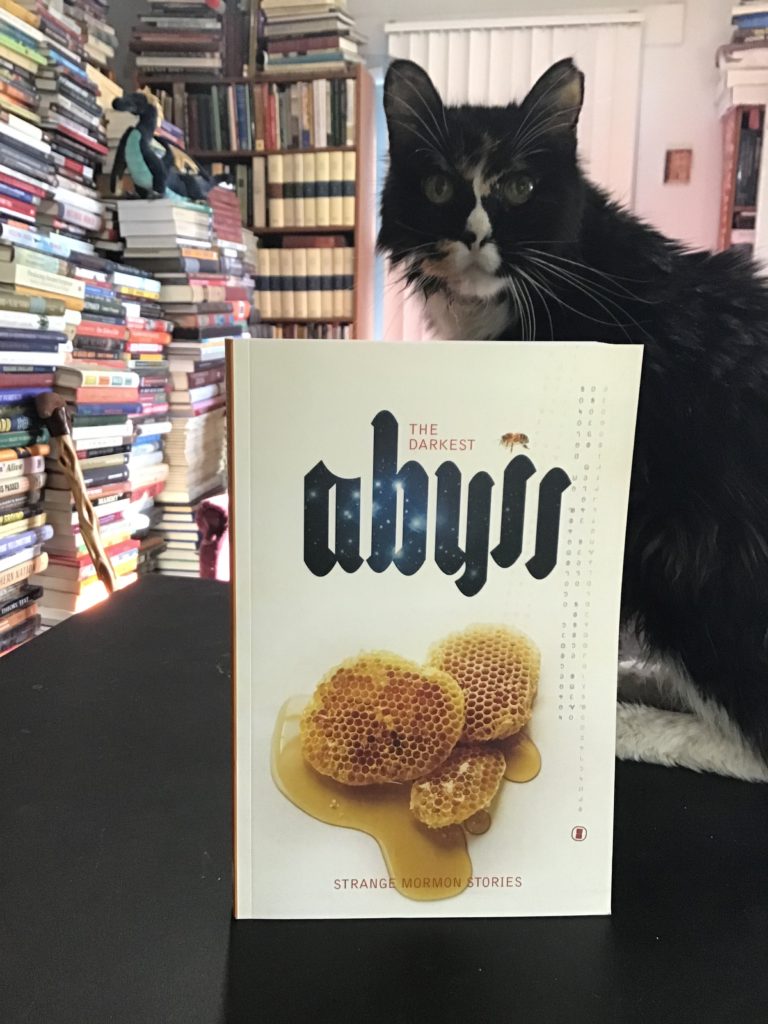

Reviewed by John Engler for the Association of Mormon Letters

I’ll confess it’s been a few years since I’ve read a new short story collection. I’ve been leaning into nonfiction for a while now, and I’d grown doubtful (probably for no good reason) about the quality of short stories written by or about LDS people, so I hadn’t been seeking them out. But then this book crossed my radar. I’m not sure why I was interested. Maybe it was the numerous tweets I’d seen, or maybe I liked the borrowing for the title from Joseph’s well-known statement about stretching one’s mind “as high as the utmost heavens and search into and contemplate the darkest abyss.” Maybe it was the allure of the cover art, or maybe it was the subtitle, “Strange Mormon Stories.” Regardless, I was interested. And from the moment I opened it, I stayed interested.

It was Eugene England who first introduced me to Mormon short stories with Douglas Thayer’s iconic 1978 collection “Under the Cottonwoods.” That dates me a little, I’m afraid, but it set my expectation for what Mormon shorts stories were about—relatable, anguished characters wrestling with faith crises. In some cases, other Mormon stories I’ve read have played into the trope of goofy Mormon practices. Both forms had a limited shelf-life for me. Morris’ collection entirely reset my expectations about the possibilities for Mormon short stories. It was just the book I needed to rekindle the delight and intrigue I first felt at reading stories that tapped into my own religious and cultural experience. Make no mistake: these are definitely Mormon stories. I imagine that non-LDS readers may appreciate the stories even without an insider’s knowledge, but having an insider’s understanding of the doctrine and culture clearly adds a great deal of backstory gravitas.

This collection is much less traditional, much less formulaic, much more experimental, and much edgier than Thayer’s collection was. It’s also much more mature in terms of the genre, which only stands to reason since we’ve had decades of short stories and cultural evolution. I haven’t looked at Thayer’s collection in some time, but I recollect that the characters were oppressed by the troubles they faced and that the themes of sin and grace loomed large in those narratives. This collection feels very different to me than Thayer’s angst-ridden, weighed-down characters. Yes, there’s still some angst here, but it’s less direct and more balanced with mystery and lighthearted joy. At times I caught myself literally giggling with delight. Anyone who knows me knows that I’m not a giggler, but there were moments of such carefree and unexpected joy that it released some bit of the forgotten inner child.

Early in The Darkest Abyss, I would start each story skeptical about whether unique Mormon stories were possible anymore, and with each story, I would find myself utterly delighted, almost giddy, with how much it surprised me, how fun it was to read. As I moved through the book, I began to expect left turns, but still, they caught me unawares. Don’t misunderstand me—these stories are not comedy-club-kind-of-fun stories. They are weighty stories, sometimes leavened with humor and absurdity but laden with deep, often-metaphorical meaning. But when I say fun, I mean delightfully clever, inventively full of literary surprise, and unexpectedly meaningful. I know, we literary people are an odd lot. This book might not be for the reader of lightweight, predictable stories with the kind of characters and plots that are well-vetted. But if a reader is looking for a trip into the delightfully absurd, this is the collection for them. There’s a stretching into dark places—and when I say dark, I don’t mean evil so much as I mean unilluminated, unexplored, and mysterious—and it’s irresistible to me. Some of the stories are simply odd and quirky, like walking through a literary fun house where reality is warped almost to unrecognizable, while other stories feel more perilous and leave readers momentarily suspended mid-air as if they’re Wile E. Coyote who’s just suddenly found himself off the edge of a cliff with nothing beneath him but the chasm to plummet into.

There are times when reading books that I am struck by the poetry or the beauty of a writer’s prose. Whenever I read My Name is Asher Lev, for example, it feels like I’m unwinding in a deep, luxurious bubble bath of decadent language—the feeling is almost palpable. As I read Morris’ book, that’s not the feeling I had at all. In fact, the more I thought about it, the more I realized that for me there had been an apparent absence altogether of the effect of the prose. While reading, I just didn’t notice it, not really at all. Just as I was considering whether I thought this was a shortcoming of the work, I realized it was part of its genius. The prose never really interfered with the story itself. What took front stage were the characters, the plot, the voice of the narrator, the crises of the moment—all the stuff of which stories are built. The writing itself is apparently so clean, so transparent, that it didn’t even ping my radar—except for the absence of its interference or its presence. That’s some serious skill.

Morris fully embraces the short story ethos. The first lines of his stories are almost always compelling in their own right and hook readers instantly. Take this one, for example, from a story titled “Wild Branches:” “When my father returned from his mission to Finland, he brought my mother home with him in his suitcase.” Wait, what?! How can a reader not be swept into a story after that first line?! Impressively, it only gets odder the more you read, not to mention more symbolic and more meaningful. Morris’ characters are often memorable, but what’s especially impressive to me, a writer who can really never get away from his own voice, is that there’s very little of a standard Morris voice in his characters. Instead, they each tend to embody their own personality and speech patterns as good characters should. I’m seriously wowed.

The stories in this collection are of wildly different lengths. He’s not beholden to a single rhythm or pattern for his stories, and a number of them are experimental in form, which adds an intellectual layer that’s not always present in traditional narrative form. That said, the experimental stories sometimes didn’t have the same compelling driving force for me, not nearly so much anyway as stories with a slightly more traditional narrative line, strong and compelling and carrying readers along. The story plots take pleasantly unexpected turns, and the way Morris embraces fantasy elements helps with this. It’s not necessarily the kind of magical fantasy that Rowling or Sanderson write, however. Instead, the stories are filled with everyday people living in a world where things are just a half-a-tick different, but where the characters just roll with it. For me, Morris’ stories settle into a tradition more akin to the magical realism of Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s stories.

I’m tempted to review each story in the collection—although I’ll spare you—because each of them is unique. (I was almost tempted to say “very unique” to emphasize how unique each is, but I was taught long ago that there are no levels of uniqueness—either it’s unique or it’s not—so it’s inappropriate to modify the adjective.) But I’m telling you that reading each story is embarking on an adventure entirely unlike the others, a peek into a vastly different world inhabited by offbeat but recognizable characters. I respect the stories so much that I don’t dare even hint at the characters or the plot for fear of denying readers the full measure of pleasure when they read them for themselves. But from the very first story, “Proof Sister Greenley is a Witch,” I was delighted. It, and all the other stories, are built on clever premises, and they revel in their Mormoness.

I will say that when I began the book, I didn’t really know what genre of stories to expect—the cover says nothing about fiction. Because I’ve been reading so much nonfiction, I was momentarily confused by a female narrator in a book by a male author. I was even more confused when I didn’t find the author’s name on the cover—which I think is a real disservice to Morris—and on my copy, there’s a typo of his name on the spine of the book, naming him Willian instead of William, which left me momentarily wondering if Willian was a female version of the traditionally male name, so I had to google Morris and verify what was going on. But once I got past all of that and realized I was reading speculative fiction written by William—well, that really cleared this up for me, and I was able to embrace the full cast of characters and narrators.

I even took The Darkest Abyss along with me on my final late-summer Jeep drive up Willard Mountain. While it was far too chilly and windy at the 9,399-foot summit, I found a lovely spot in full solitude for miles in every direction at around 8000 feet, with a view few people will ever see overlooking the fading fall colors of the remote valleys below. I pulled out the book, and in the fading light of day, I read the story “Last Tuesday,” which tells of an unexpected encounter. I don’t dare say more about the story than that, but I will add that the story is so compelling that for a moment I imagined having a similar encounter in that remote place and lovely place, which is exactly the kind of place I felt like I visited each time I picked up Morris’ book.