Reviewed by Chad Curtis, Jan. 23, 2020

Reviewed by Chad Curtis, Jan. 23, 2020

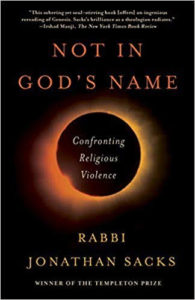

Serendipitously I picked up two books this past week that complement each other to a T: Not in God’s Name: Confronting Religious Violence by Rabbi Jonathan Sacks and The Book of Laman by Mette Harrison. Both wrestle with the tensions between religious communities and individuals. Harrison’s book is essentially a Latter-Day Saint microcosm of Rabbi Sacks’ thesis, that the religious brand of violence between/within Islam, Christianity, and Judaism is an inherited sibling rivalry. While Harrison’s book is a narrative, it plays with traditional interpretations of the Nephi versus Laman and Lemual narrative that paint the story completely black and white.

Dualism

Dualism

While I had heard the concept of dualism before, I hadn’t entertained its theological implications, or even that it had anything to do with my own religious faith. Dualism is the idea that the central conflict in the world is between the forces of good and the forces of evil. In a religious context, this is between God and some evil counterpart, for instance, the devil. I thought Christians were technically exempt from being classified as dualists, because the devil is temporary and only holds temporary power. But Sacks is worried about the functional role of dualism: how your theological beliefs of good and evil inform your interactions with others. Take this quote on what Sacks calls altruistic evil:

Altruistic evil is not normal. Suicide bombings, the targeting of civilians and the murder of schoolchildren are not normal. Violence may be possible wherever there is an Us and a Them. But radical violence emerges only when we see the Us as all-good and the Them as all-evil, heralding a war between the children of light and the forces of darkness. That is when altruistic evil is born.

Sacks take terrorism back to its ideological roots: it isn’t done blindly, but with ideological, and often religious motivations. But Sacks argues that this isn’t done because of religion. It is dualism, not religion, that results in radical violence of this sort, and dualism has many secular counterparts. All you need to be able to do is argue that a group out there is to blame for everything bad, and your group represents everything good. Sacks develops this idea about why dualism can be so appealing:

Dualism is what happens when cognitive dissonance becomes unbearable, when the world as it is, is simply too unlike the world as we believed it ought to be… dualism ‘denied the unity and omnipotence of God in order to preserve his goodness.’

Dualism is giving up on trying to wrestle with complexity. There is wisdom in that line from Obi Wan Kenobi: Only a Sith deals in absolutes.

As a Latter-Day Saint, these cords struck home because I often feel that we engage in language very similar to what Rabbi Sacks is talking about here. We engage in forms of dualism. There are many a conference talk where a general authority puts his hands close together, then pulls them slowly apart to demonstrate some variation of “the standards of the world and the standards of the Church are getting farther apart.” We don’t have a strong tradition of self-criticism, looking for the evil within rather than without, a key point that Sacks calls as a cure for dualism. Rabbi Sacks actually calls the entire Old Testament an exercise in self-criticism. We more often than not paint ourselves as victims– despite the theological case in the Book of Mormon that we are agents “to act and not to be acted upon.”

The cure for dualism is explained so eloquently by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who lived through the gulags of the Soviet Union:

If only there were evil people somewhere committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being.

The real battle is inside the human heart. We need not look for someone to blame. The greatest in our religious traditions is that which internalizes the battle between good and evil, that truly recognizes our flawed nature.

I feel that we have plenty of material to work with in our tradition to combat dualism. But, interestingly enough, we get off to a bit of a rough start if you open up to the first chapters of The Book of Mormon. The story begins with Lehi and his family departing from Jerusalem because the prophet-father Lehi has been told by God that Jerusalem is to be destroyed for its wickedness. But it doesn’t take very long for the family to split into the righteous and obedient Nephi versus his murmuring and wicked older brothers Laman and Lemuel.

Just by chapter 3, we have a verse where Nephi is directed by God to slay Laban in order to obtain the plates of brass. Nephi records the promptings of the spirit as:

Behold the Lord slayeth the wicked to bring forth his righteous purposes. It is better that one man should perish than that a nation should dwindle and perish in unbelief.

Nephi’s justification has never sat right with me, and I feel that Rabbi Sack’s explanation of dualism is very useful here. This justification for slaying Laban relies on a cosmic narrative between the wicked and the righteous. Some violence is OK as by the righteous as long as it furthers righteous causes. Now, Latter-Day Saint general authorities are unequivocal today that the Spirit will never tell them to kill anyone. But if you go to the depths of Latter-Day Saint Twitter, you will find someone make the argument that “you have to be ready to do anything the Lord may ask you, even kill, as we are living in the latter days after all.”

This is before we even jump into the tensions between Nephi and his brothers. The clever thing Mette Harrison does in The Book of Laman is she writes it from the point of view of “the bad guys”. When I first explained it to my parents, their first reaction was, “Oh! Like Disney’s Maleficent, right?” A fitting comparison. In the traditional narrative, Nephi is the obedient son willing to do whatever the Lord asks of him, no questions asked. This is a model of obedience for every Latter-Day Saint. When the prophet speaks, you listen. On the other hand, you have Nephi’s brothers, Laman and Lemuel, who, when they aren’t murmuring, are tying their brother Nephi up apparently without justification. In the forward of the book, Michael Austin points out how this seems to fall flat as a narrative: Simply put, we want the Book of Mormon to be history, not fiction, but we expect the people in it to act like characters in a (not very good) novel and not as the kinds of people who have actually ever existed.In my experience, I have never met someone like a Laman or Lemuel who just is that wicked. The characters are extremely 2D, at least when traditionally interpreted. What Harrison does is she relates the narrative from Laman’s perspective. From this angle, we actually see why Laman acts the way he does. To achieve this, Harrison does have to add some things that aren’t in the scriptural record. One of my favorite takes is that Lehi wasn’t always a prophet, and he has a bit of a checkered past: he abandoned his family as a drunk during the childhood years of Laman and Lemuel. When he comes back as a changed man and begins to prophesy, it is difficult for Laman to forgive him, hence his reluctance.

I know that isn’t doctrine. But it does one thing that is very important: it removes the idea that the world is split into good and evil people. Nephi and Lehi potentially had their flaws. Laman and Lemuel had virtues. And when you try to picture that Nephi and that Laman, you break the dangers of dualism in the present day too.

Sibling Rivalry

Perhaps my favorite aspect of Sacks’ book is his extended interpretation of the sibling rivalries in the Book of Genesis: Cain and Abel, Isaac and Ishmael, Jacob and Esau, and Joseph and his brothers. The theme of sibling rivalry is central to the book of Genesis, but I have never actually thought to examine it as a theme. Probably because I’ve been accustomed to interpreting it as good versus evil rather than clashes between siblings.

Sacks points out that all three of the monotheistic religions– Islam, Christianity, and Judaism– claim to be the true heirs of the Abrahamic covenant. And by doing so, the existence of the others’ claim is a challenge to their own authority. Sacks takes each narrative of sibling rivalry in the Old Testament and shows how the surface narrative suggests sibling rivalry is inevitable and a “good” son emerges. But there is always a counter-narrative where the siblings are reconciled. In the end, the message of Genesis is that yes: God chose a people. But he never rejected another people. Each child had his own unique destiny and his own relationship with God.

You don’t even need to go far beyond the text of the Old Testament to see that this is the case: an angel saves Hagar and Ishmael after Abraham sends her out into the desert at Sarah’s request. There is a divine influence and favor over the Ishmaels and the Esaus in the world. God never rejected them. What if the same were true in the story of Laman and Lemuel?

That is what Mette Harrison does with her story. She shows the spiritual life of Laman that is skipped over from Nephi’s perspective. Read this beautiful passage where Laman for the first time feels God speaking to him:

I felt a pressed to the chest, though, and I was sure I could feel another heart beating next to mine. This heart was deep and wide enough to fill an ocean, yet delicate enough to answer my own blood’s question.

I love you, the heart told me. And the pressure of the arms. And the chin that I felt just above the top of my head.

I love you. Though you run from me. Though you do not trust me… Though you may not repent or grow wiser or kinder or greater than you are.

Still, I love you.

From Nephi’s point of view, it seems that any repentance or goodwill by Laman and Lemuel is short-lived and insincere. But what if God were in their story the whole time as well? The Book of Mormon suggests that that is the case, at least for his descendants.

Jacob teaches that in many aspects the Lamanites were more righteous:

Behold, ye have done greater iniquities than the Lamanites, our brethren. Ye have broken the hearts of your tender wives, and lost the confidence of your children, because of your bad examples before them; and the sobbings of their hearts ascend up to God against you.

In fact, the Lamanites were a very loving people:

Behold, their husbands love their wives, and their wives love their husbands; and their husbands and their wives love their children… wherefore, how much better are you than they, in the sight of your great Creator?

These are moments in the Book of Mormon where the Nephites wrestle with the dualistic narrative they have been presented with, and we would do well to continue that wrestle. Harrison’s book is a good reminder to challenge the narratives we tell ourselves.