Review

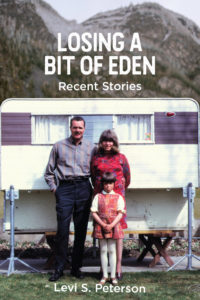

Title: Losing a Bit of Eden

Author: Levi S. Peterson

Publisher: Signature Books

Genre: Short Story Collection

Year Published: 2021

Number of Pages: 248

Binding: Paper

ISBN: 9781560852926 (paperback; also available in ebook, of course)

Price: 14.95

Reviewed by Julie J. Nichols for the Association of Mormon Letters

In the mid-1980s, the community of Mormon letters was abuzz with Levi Peterson’s Cowboy Jesus. The Backslider won the 1986 AML award for the novel, and everyone was talking about it, admiring both the audacity and the comfort of the casual Jesus in spurs rolling a cigarette amiably and forgivingly with the eponymous wayward soul at the end of the book. (Terryl Givens reports in Stretching the Heavens (220) that Richard Cracroft, then chair of the BYU English Department, was not so enamored.) That wasn’t the first time we saw Peterson’s unorthodox approach to depicting Mormon dilemmas: since 1978, he’s been winning awards and publishing short fiction and essays in Dialogue and Sunstone (see a bibliography here), and the University of Utah published both his award-winning biography of Mormon historian Juanita Brooks and his own autobiography, Rascal by Nature, Christian by Yearning. Wikipedia summarizes Peterson’s long life (he’s 88) in Mormon letters by pointing to his status as emeritus professor of English at Weber State University, his role as president of AML (1980-1982 and 1989-1900), his stint as editor of Dialogue (2004-2008), and his insistence that his students “write beyond their inhibitions” as part and parcel of his 1987 “Defense of a Mormon Erotica,” among other notable accomplishments.

Now Peterson has a new collection. Of the ten stories in Losing a Bit of Eden, three are new. Six of the other seven have been published in Dialogue, from “Badge and Bryant” in 2010 to the AML-award-winning “Kid Kirby” in 2016, to 2019’s “Bode and Iris.” “The Return of the Native,” one of my favorites because of its closeness to my own experience rejecting home and then returning, was published in Sunstone in 2011.

All of the stories in Losing a Bit of Eden exhibit Peterson’s signature voice, setting vibe, and style; all are highly entertaining to read. All tug and tease at both heart and mind.

If you’re not familiar with Peterson’s work (and, even more enjoyably, if you are), you can expect a wry narrative voice just a notch above what you’d expect the protagonist’s diction level to comfortably be. In other words, the narrative voice exceeds the protagonist’s grasp, to the reader’s smug satisfaction, so that the dialogue is often, hilariously, in a somewhat different register than the narrative voice:

When Badge and Bryant had completed their leisurely meander from the high school, they seated themselves on the edge of Badge’s porch. Badge needed to expatiate further upon his newfound pleasure, it being his nature to emote, enthuse, and think out loud. He also felt obliged to orient his less imaginative cousin to the satisfactions with which [a shotgun] wedding swarmed…

“How about we make a pact?” Badge said abruptly…. “We’ll get different girls pregnant. Their fathers and brothers will come after us. They’ll rough us up and drag us in front of the bishop and make us marry them.” (32)

The effect is to invite the reader (at least this reader) into two personae: a) “I’m smarter than the protagonist, more sophisticated, more educated, but b) somehow the protagonist knows this and still reaches out to me so I ‘get’ him, I feel for him, I see what he’s enduring.”

What the protagonist is enduring is sex, really, just natural sex-drive sex, not porn or perversion, just the yearnings of any ordinary human being. Usually male. (More on this in a moment.) The object of his desire is outside of marriage and/or outside of Mormondom, so the desire is fraught. The protagonist is caught between nature’s call and God’s commandment, between the loud story of his loins and the strict story being levied upon him by the Lord’s supposed anointed.

Of course, we’re sympathetic! How could we not be? It’s the predicament of all the Calvinist faithful: be good or be happy. You can’t expect to be both.

Peterson’s stories all have a feel of the Old West, even when they’re obviously taking place in the twenty-first century. (Not all of them are—he dates some of them clearly at the end of the nineteenth, or the middle of the twentieth.) The main characters are all males swimming in their hormones. All the stories take the reader on a journey from relative innocence (the awakening of sexual desire seems to take many of them by surprise) to relative resignation, that is, from sincerely just following one’s newly awakened desire to earnest resolve. Usually, that resolve is simple: find a way to keep following one’s drives even though Somebody says one’s not supposed to. Or in other words, figure out how to marry the gentile girl, or kill the bad guy, or even sleep with the bishop, in the most community-approved way.

The “journey” (I think Peterson would wince to hear his stories made archetypal) is richly recounted, detailed, impossible to misunderstand. Ambiguity is the bane of the protagonist. What he wants to do is get rid of it and get back to simple straightforward life, with the girl, with his name exonerated. In every story, Peterson’s in total command of his craft and his content. If Cowboy Jesus caught your attention, these stories will too.

The three new ones are the title story, “Cedar City,” and “Bachelor Stallions.” They’re not, thank God/dess, concerned about the pandemic, conspiracy theories, or global warming. They’re local, literal, focused on the consequences of acts of nature, the tug and pull of responsibility in the face of unintended situations and uncontrollable responses. It’s that call to responsibility that eventually brings the actors around. Morality is the drive to be responsible after you’ve given in to the drive to mate. The latter is private pleasure; the former is a public admission that you did the deed and are willing to do what you have to do to regain acceptance in the public eye.

All that is signature Levi Peterson. It’s entertainment; it’s Mormon literary history; it’s Mormon culture thrown into the arena of other-than-Mormon nature. It asks, “What’s Jesus enough? What kinds of stories leave Eden intact? Were we ever really innocent to begin with?” Probably not. And it’s okay. Jesus-enough will open the doors of forgiveness. Cowboy Jesus will let us go on.

What a thoughtful review of a book by a wonderful storyteller!

Julie —

Way-belated thanks & kudos for a review that does some justice to this collection. I’ve not kept track of AML as closely as i ought, and read this for the first time last night. I regret to think that more potential readers may not see it than have seen the seriously distorting and damaging review in Dialogue the summer after you posted this one, though Karen Rosenbaum’s Letter to the Editor the following year did some helpful repairs.

bwj