Review

———–

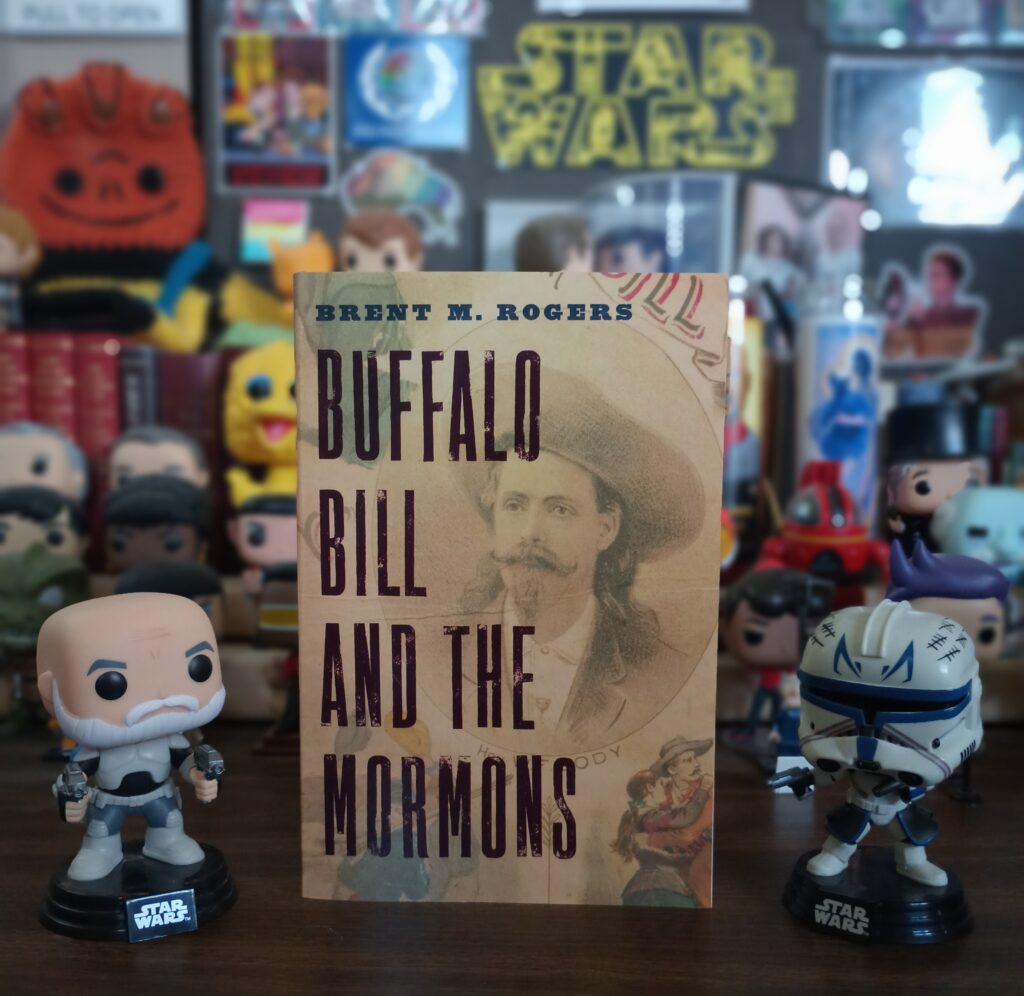

Title: Buffalo Bill and the Mormons

Author: Brent M. Rogers

Year Published: 2024

Publisher: University of Nebraska Press

Genre: Western History, Mormon History

Format: Paperback

ISDN: 9781496213181

Price: $29.95

Pages: 291

Reviewed by Kevin Folkman for the Association for Mormon Letters

William F. (Buffalo Bill) Cody’s interactions with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons to Cody and his contemporaries) make for a revealing and engaging story in the new book “Buffalo Bill and the Mormons” from the University of Nebraska Press. As historian Brent Rogers notes in his introduction, Buffalo Bill and the Mormons share a “history about creating narratives, those that were true and those that they wanted to be true” [p11].

Those narratives mattered to both parties. Cody was a showman, passionately interested in promoting his stage persona, regardless of the facts. Cody was arguably one of the best-known American celebrities of the late 19th and early 20th centuries for his plays, dime novels, and especially his Wild West shows that played throughout the United States and Europe. Cody promoted himself as the brave Western cowboy, nurturing the image of superior masculinity, courage, and virtue to sell tickets and finance his business ventures. At the same time, the LDS Church was struggling to redeem its image on the national scene after years of suffering under persecution for its practice of polygamy. The Church’s narrative involved projecting an image as wholesome patriots building communities in the arid West through agriculture, irrigation, and industry.

What is so interesting in Roger’s new book is how those competing narratives came together at key times for the benefit of both parties. Cody claims to have been an eleven-year-old teamster and laborer with Johnston’s army that marched west to put down a reported rebellion in Utah. It’s clear that Cody was employed in various capacities by the Army in 1856 at the time that the Utah Expedition was preparing to head west, but there is no firm evidence that Cody actually traveled with the troops and wintered in Wyoming. Later, after serving as a scout for the U.S. Cavalry, Cody began to embellish his resume, playing a role in stage productions as a rescuer of damsels in distress from Mormon agents trying to lure unsuspecting young women into polygamy. Playing to the national obsession with polygamy, Cody rapidly gained fame and fortune with his portrayal of a heroic rescuer, facing off against Brigham Young and Danite avengers.

When the Church issued a ban on polygamous marriages in 1890, efforts were put forward to show that Mormons were exemplary American citizens. Cody, on the lookout for business opportunities, toured Northern Arizona and much of Utah in 1892 in the company of Brig Young, a grandson of Brigham Young; Junius Wells, son of Apostle Daniel H. Wells; and other Mormon officials, along with a cadre of European military leaders. Cody was looking to expand his business beyond his wild west shows. Over the course of several weeks, Cody and his companions traveled through the Grand Canyon, the Arizona Strip, and Southern Utah, staying with Mormon families. Cody then met with the church’s first presidency in Salt Lake City. Impressed both with the wholesome nature of the LDS families he met along the way and the industrious nature displayed in community building through cooperative labor, Cody’s attitude towards the Church began to change. The next year, Cody’s Wild West Show and Congress of Rough Riders played to sold-out crowds at the Columbian Exhibition and World Fair in Chicago, but without the evil subplot of Mormon polygamy. Inside the gates of the World’s Fair, the Mormon Tabernacle Choir entranced audiences and the official Utah State exhibit touted the marvels of desert irrigation and agriculture to great acclaim.

At the same time, Cody was trying to develop the Big Horn Basin in Wyoming where he owned thousands of acres along with water and mineral rights. However, such a large-scale project demanded lots of cash and an extensive canal system to bring water to otherwise unusable dry lands. Familiar with the Saints use of irrigation in Utah and surrounding areas, Cody reached out to acquaintances in and associated with the Church in hopes of luring Mormon settlers to the Basin. The Church at the same time was looking for new territory to send recent immigrant converts to settle. Both Cody and the Church found common ground where their individual narratives coincided. Mutual interests, however, did not mean a lack of complications, and neither Cody nor the Mormon settlers got all they wanted out of the arrangement. Yet in the end, Cody and the Utah church ended as friends and cooperative partners, overcoming decades of misunderstanding and prejudice.

In “Buffalo Bill and the Mormons,” Rogers has written a compelling and little-known story, vibrantly written, and thoroughly researched. “Buffalo Bill and the Mormons” tracks both the changes in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and its perception by the American public through the eyes of its premier frontier showman. The closing of the American Frontier coincided with the opening of the nation to a more favorable view of Utah and its predominant religion. “Buffalo Bill and the Mormons” stands as an important addition to the literature of that transition.