Review

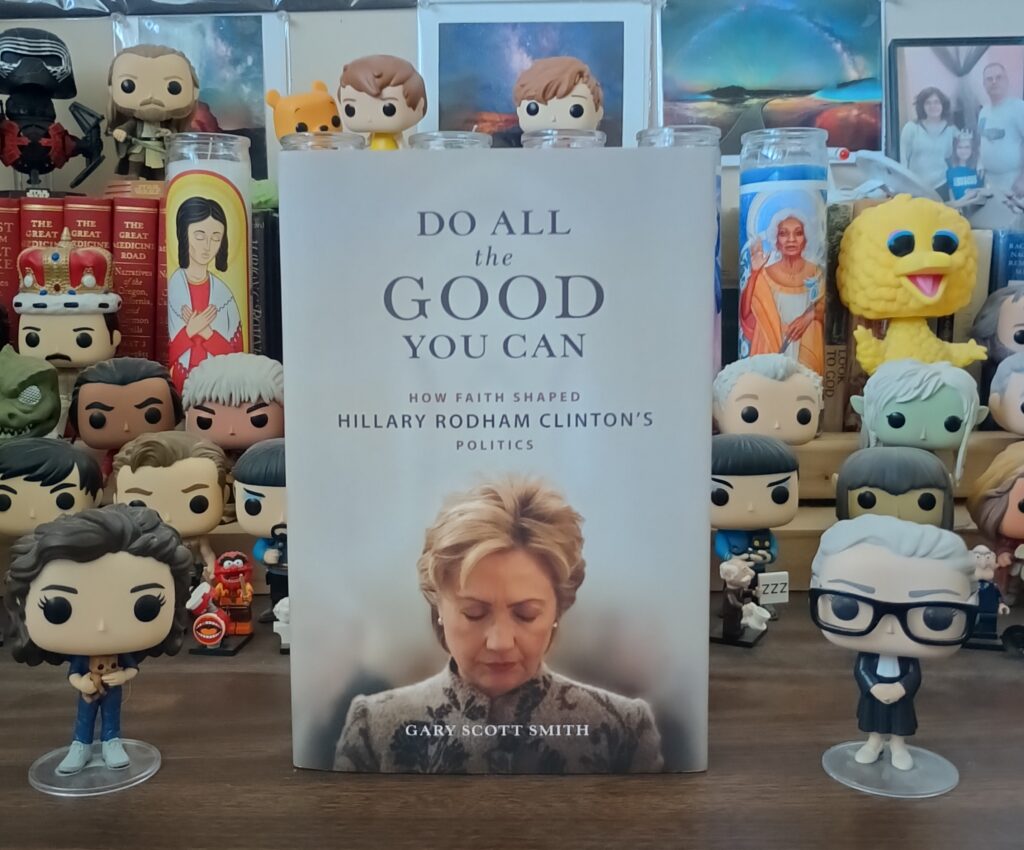

Title: Do All the Good You Can: How Faith Shaped Hillary Rodham Clinton’s Politics

Author: Gary Scott Smith

Publisher: University of Illinois Press

Year Published: 2023

Pages: 308

Format: Hardback

Genre: Biography

ISBN: 9780252045318

Price: $29.28

Reviewed by Kevin Folkman for the Association for Mormon Letters

Few public figures have been more polarizing than Hillary Rodham Clinton. Philanthropist, First Lady of the United States, Senator from New York, Secretary of State under President Obama, and two-time presidential candidate, Clinton has been labeled as a demon-worshipping fiend with no religious feelings, a radicalizing political opportunist, and as the country’s most significant female politician. Gary Scott Smith, Emeritus Professor of History at Grove City College in Pennsylvania, has written about Clinton in his political biography Do All the Good You Can: How Faith Shaped Hillary Rodham Clinton’s Politics. In it, he argues that Clinton is a prime example of devout Methodism, committed to following John Wesley’s creed of “Do all the good you can, by all the means you can, in all the ways you can, in all the places you can, at all the times you can, to all the people you can, as long as ever you can” [p 5].

Smith has previously written biographies of other public figures’ religious leanings, including Winston Churchill, George Washington, and Mark Twain, as well as several texts on the intersection of faith and politics. In Do All the Good You Can, Smith tells the history of Hillary Clinton’s religious faith, from her childhood in Illinois, through her college experience, Yale Law School, her involvement in politics, and as the wife of Arkansas governor and 42nd US President Bill Clinton In her own right, she forged her own political career as a US senator, Secretary of State, and presidential candidate. The result is a highly detailed analysis of her faith, its impact on her political life, the personal impact of that faith in dealing with her husband’s very public marital infidelities, and two demanding and mean-spirited presidential campaigns.

What emerges is a multifaceted account of how a highly intelligent and ambitious public figure navigates the challenging, and at times tortuous path of reconciling one’s personal faith with one’s highly visible public actions. Did Hillary try to live up to Wesley’s admonition? Did she lie? Did she truly care about the welfare of others, especially those least able to advocate for themselves? Was she at times self-serving in her actions? Was her forgiveness of husband Bill’s public admissions of an affair with an intern while serving in the White House sincere? Smith has supplied substantial evidence for these and other questions but leaves the final judgment to the reader.

The greatest value of such a study of religious faith is to allow the reader to examine their own lives and vicariously live through the experiences of another. Do All the Good You Can serves as an interesting complement to this reviewer’s recent reading of Romney: A Reckoning, in which Mitt Romney’s business and political career was examined in light of his Mormon faith. Romney is in many ways the antithesis of Clinton, his conservatism opposed to her progressive liberalism, and his privileged upbringing compared to her middle-class childhood. Both were strongly influenced by their religious traditions and experiences as children and young adults. Strikingly, both view public service as an extension of their respective faiths. Both have had to handle highly public setbacks and embarrassments, and both have relied on their core religious beliefs to confront the challenges their public lives have brought them.

Smith has mostly succeeded in his effort to highlight Clinton’s faith journey through public life. The text is readable, never condescending, and not burdened with overly academic vocabulary. The documentation is substantial, leaning heavily on Clinton’s writings, speeches, newspaper and magazine articles, and the recollections and observations of friends, journalists, and staff members. One notable anecdote is from Yale Law classmate Robert Reich, who served as Secretary of Labor in the Clinton administration. In the Yale class that included Reich, Hillary, Bill Clinton, and future Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, Smith writes how the four interacted in a civil liberties class:

“…every time the professor asked a question, Rodham’s hand went up first, and whenever she was called upon, she answered correctly. Reich often volunteered answers, which were right about half the time. Thomas never said a word, and [Bill] Clinton spent much more time doing political work than attending class.” [p36]

Clinton, according to Smith, never abandoned her efforts to do good personally and was often trying to use whatever influence and power she had to organize and mobilize others to share in those efforts. However, after a grueling first two years in the White House, where her efforts to promote initiatives to provide universal health care failed, coupled with pushback from some of her more public professions of faith, Clinton admitted at a National Prayer Luncheon that she was “…hesitant to discuss religious ideas again. She was astonished to realize that many people thought spirituality should…not [be] brought out into the public arena” [p 61].

As a result, Clinton’s public professions of faith grew fewer, even as her influence and power grew as a Senator from New York and President Obama’s Secretary of State. That did not stop her private exercise of faith. Smith shows how Clinton continued to act in accordance with her religious feelings and interacted with various other faith groups, including Catholics, Mormons, Muslims, Jews, and evangelicals.

This reviewer did, on occasion, find Smith’s comprehensive detailing of Clinton’s religiosity redundant. At notable points in Clinton’s public life, Smith writes of the many times Clinton’s faith was referenced, observed, and commented upon, a practice that sometimes felt redundant. There is also the issue of the documentation of a speech on the role of religious faith in the public arena that Clinton made in 1993 to an audience of 14,000 at the University of Texas at Austin. Well received by some and sharply criticized by others, this address seemed to loom significantly in her subsequent career. As cited in the notes, her address is referenced exclusively from news reports and articles. No citation or link is listed to the actual text of the speech. For an event that is claimed to have been a watershed moment, as Smith asserts, it would have been useful to include a direct citation or link to the full text or to state that such a transcript could not be found. Instead, we are left to only read the reactions of others and have no opportunity to make our own analysis.

Despite these occasional shortcomings, Smith’s Do All the Good You Can works as intended as a useful addition to the ongoing debate over the role of religion in public life and the personal religiosity or lack thereof of our public figures. With outward manifestations of religious faith in the public arena in decline, such a personal examination of a political leader’s faith is increasingly rare, yet arguably all the more important. Do All the Good You Can, can be a reassuring nod to the continued presence, however private, of religious faith in the United States.