Review

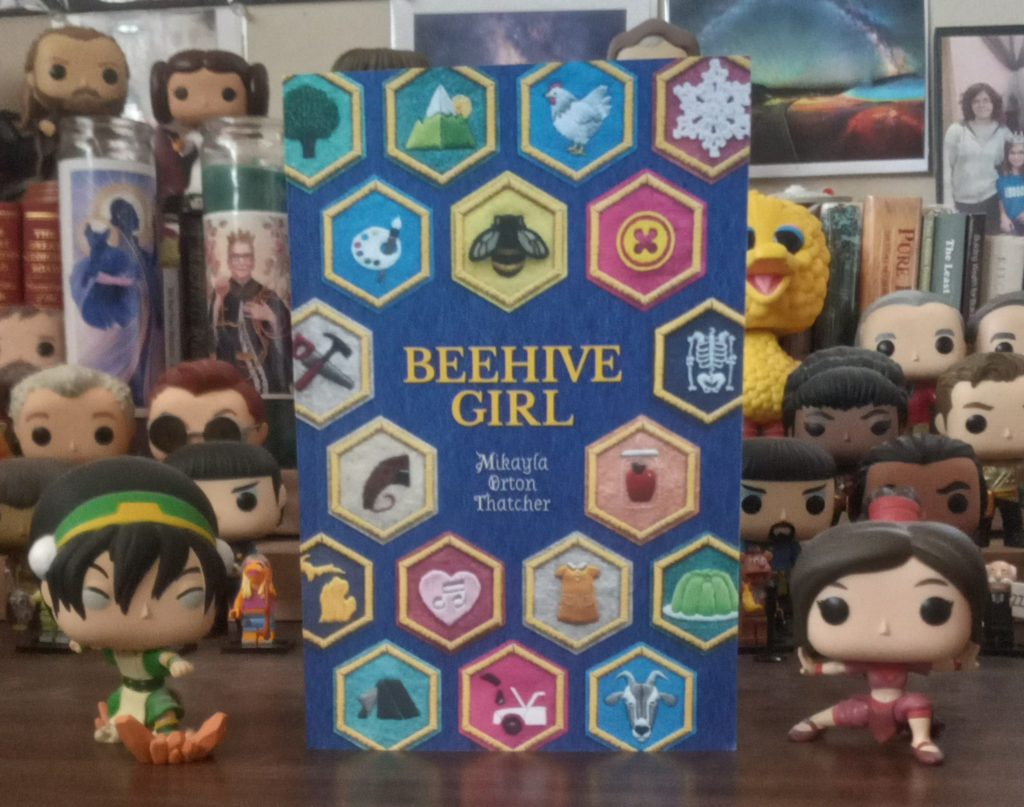

Title: Beehive Girl

Author: Mikayla Orton Thatcher

Publisher: BCC Press

Genre: Religious Non-Fiction

Year Published: 2023

Number of Pages: 374

Binding: Paper

ISBN: 978-1948218825

Price: 12.95

Reviewed by Kathryn Lindsey for the Association of Mormon Letters

At its core, Beehive Girl is a nostalgic and delightful tribute to Mormon womanhood. Thatcher weaves history and personal experience into a tapestry of identity that connects readers across generations and across the spectrum of Mormon orthodoxy. Despite its simple premise I found myself deeply moved and have been eager to personally recommend this book to many women in my circle.

After stumbling across a New Era article in which she first learns of the Personal Progress Predecessor “Beehive Girls” (1915-1970), Thatcher embarks on a mission to work her way through the program and “earn” her Beehive Girl award. While some of the Beehive Girl activity “cells” will feel familiar to those who completed Personal Progress, the Beehive Girls program is undeniably more expansive. Alongside the (mostly) spiritual pursuits that a modern Young Woman might check off in her Personal Progress book, Beehive Girls were given such options as making furniture, climbing a mountain, caring for a beehive, plucking and dressing a chicken, writing essays on vocations for women, and giving accounts of women in Church service, among many others.

Thatcher details her experiences attempting a range of these activities, with varying (and relatable) degrees of success. I found myself laughing on one page and weeping on the next. Some of the activities blended seamlessly into modern life, while others felt like a visit to the frontier museum. At some turns, I was struck by how antiquated the program itself felt, with its endearing-but-hokey slogan “WOMANHO” and recommendation in the program-associated Young Woman’s Journal that one avoid “drugstore concoctions” for hair cleansing. At others, I was surprised by its relative progressiveness—I certainly can’t imagine any modern church publication for young women including a frank discussion of the menstrual cycle and anatomical diagrams. The program provides a glimpse into the day-to-day lives of Mormon women that gives them a dimension and depth so often missing from somber-minded religious records alone.

Thatcher interlaces her own experiences with the history of the program and the stories of prominent Mormon women. In doing so, she gives voice to a unique and meaningful identity spanning generations. The creation and implementation of the Beehive Girls program and its associated publications were a decades-long labor of love from mature LDS women to the young women following after them. While I ultimately agree with Thatcher that this kind of program is much too big and complex for the modern church, I couldn’t help but feel some sense of loss for a program that encouraged young women to take an active role in so many facets of life. Reading Beehive Girl touched on an identity that I think many Mormon women will find deeply personal. I highly recommend Beehive Girl to the devout and the nuanced Mormon woman alike.