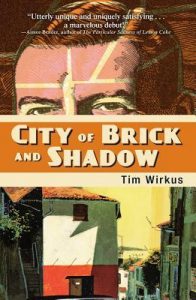

Author: Tim Wirkus

Author: Tim Wirkus

Title: City of Brick and Shadow

Gallery Books, 2014. 304 pages.

Reviewed by Robert Raleigh, Feb. 18, 2019

Tim Wirkus’s City of Brick and Shadow, like his second novel, The Infinite Future, is a book with multiple layers. On its surface, it’s ostensibly a mystery, complete with Holmes and Watson-like sleuths who just happen to be Mormon missionaries in Brazil. The Holmes character, Elder Toronto, is a brilliant and well read deep thinker who, like Holmes, sees beneath the surface of things, his mind working furiously through the evidence to figure out not just physical things, but psychological matters. His companion, Elder Schwartz, only barely speak Portuguese and is fairly dim-witted. His main goal in life appears to be to do what people expect of him, to slide by with the least amount of trouble or friction. The disappearance of their most recent convert, Marco Aurelio, is the mystery they seek to unravel.

Intertwined with this story is the story of The Argentine, a mythical crimelord who rules the slum where the missionaries live and work. The story of The Argentine is very Borgesian in nature, doubtless no accident, as Borges himself is probably the most famous Argentine, at least in literary circles. The Argentine, bored by his criminal conquest of the slums, moves on to attempting to catalog human cruelty. Along the way, he creates an underground labyrinth (labyrinths having held a particular fascination for Borges) that allegedly serves as both a way to spy on the inhabitants of the favela, in the pursuit of cataloging their cruelties and of storing the resultant records (the storage of the records resembling a dark, twisted version of Borges’s Library of Babel).

Another layer of this book is the description of Mormon missionary life, which is spot on and highly amusing. Wirkus captures well the claustrophobic feeling of having a missionary companion, and especially of having one you don’t like very well (true in this case of both of the companions, of course), since you must spend every moment of your life with this person when you’re a missionary. He also captures the maddening aspects of the authoritarian and bureaucratic machinery that pervades missionary life. These aspects seem almost incidental, however; they’re just part of the scenery, so to speak.

The real subject of the book, to me, was the quest for knowledge. In many respects, the book felt allegorical. Toronto and Schwartz were stand-ins for anyone who seeks knowledge, and they represented wildly different approaches to that endeavor. Schwartz represents someone who is dragged into the pursuit of knowledge by circumstances outside his control, unwillingly and largely unwittingly. Toronto, on the other hand, is a dedicated and fierce seeker of knowledge, regardless of the cost.

SPOILERS BELOW

[One important thing that leads me to this conclusion is the way that the mystery story, as mystery story, is cut off at its climax. Just as the missionaries are closing in on the solution to the mystery, they are interrupted by violence. Many questions are left unanswered. What actually happened to Marco Aurelio? Was Luis really The Argentine? What was the role of the cops and the pseudo “Brillo”? What was Cabral’s interest and role in all this? Was Marco trying to pull off his ultimate con? Just as we appear to be headed towards the answers to all these questions, but mystery hunt is ended by an act of brutality, the beating of the two elders.Now we suddenly cut to some point apparently many years later, the exact amount of time indeterminate. Schwartz, true to the characteristics we have already seen from the earlier story, is floating along on the surface of a normal Mormon life, with a wife and kids, living in a suburb, contemplating getting involved in a multi-level marketing scheme to sell a miracle juice. Toronto suddenly shows up in his life, as if accidentally, but we doubt (as does Schwartz) that this is actually an accident. Toronto is still trying, all these years later, to unravel the mystery of Marco’s disappearance. He has continued to dig, in spite of having been disfigured by the terrible violence that was obviously meant to deter the missionaries from continuing to try to solve this mystery. He has, he believes, reached a possible solution. Would Schwartz like to hear it? While admitting, contrary to his claims, that actually has given some thought to this mystery in the intervening years, Schwartz refuses to be dragged once again into the Watson role he played to Toronto’s Holmes. He wants nothing whatsoever to do with the case or the solution. Toronto, disappointed, drives away.Why are we left hanging, like this? Many readers were deeply disappointed by this turn of events, feeling cheated by Wirkus’s refusal to wrap things up, which is the standard denouement for mystery novels. I believe, though, that since the real subject of the book is epistemology, that this allegory is designed to teach a certain kind of lesson: the search for knowledge is long and hard, and sometimes even brutal. There may well be no answers at the end. Is the search worth all the trouble? Every person must decide this for themselves. Who do we pity more at the end of this story? Toronto, for dedicating his life to a possibly unsolvable mystery, the “pathetic” detective stuck forever in this labyrinthine past? Or Schwartz, for not caring, for being so gutless, for surfing through his life in such a way that he can’t even think critically about an obvious pyramid scheme, uninterested in the truth? This is the question, I believe, that City of Brick and Shadows wants us to ask of ourselves. ]